Behind the scenes, yet on the front lines: Epidemiologists reflect on a pandemic year

Anna Halloran woke up to a phone call in the early morning hours of March 14, 2020.

A local physician was on the line with grim, albeit anticipated, news: The first positive case of COVID-19 had been confirmed in Spokane County.

It was go-time. Halloran, the on-call epidemiologist at the Spokane Regional Health District, alerted her supervisor and then-Health Officer Dr. Bob Lutz, and eventually the whole epidemiology team, to respond.

She headed into the office, while some worked from home, to respond to four cases: three in Spokane County and one in Lincoln County.

Halloran called the first COVID-19 patient in the county and worked with the person and their family for several hours. Investigators were mounting full contact tracing and case investigations, trying to track down all contacts of those diagnosed with COVID-19 to try to contain the disease, a strategy that remained intact until case counts became overwhelming.

This meant Halloran had to reach out to about 10 people connected to that first case, advising testing in some cases and isolation in others.

One person who needed to get tested told Halloran they needed to take their child with them for the test.

Halloran said Lutz advised her to tell that patient to wear a cloth face covering to protect the child, the first time she would advise that to a patient and months before Lutz issued the county mask mandate in mid-May. The statewide mask mandate did not go into effect until June.

March 14, 2020, was, as Halloran put it “when things started to go bad.” After a month and a half of watching outbreaks in Western Washington, the pandemic had arrived for Spokane County.

Epidemiologists are accustomed to disease outbreaks, the unknowns that necessitate investigations. Their very job descriptions and training enable them to detect, connect and identify disease, its vectors and how far it can spread.

The health district had four staff epidemiologists when the novel coronavirus officially arrived in Spokane County. At the time, there was some hope that the virus might mirror H1N1,phasing out seasonally, or at least not spreading as quickly as it did. Even in March, seasoned public health professionals knew it was too late, however.

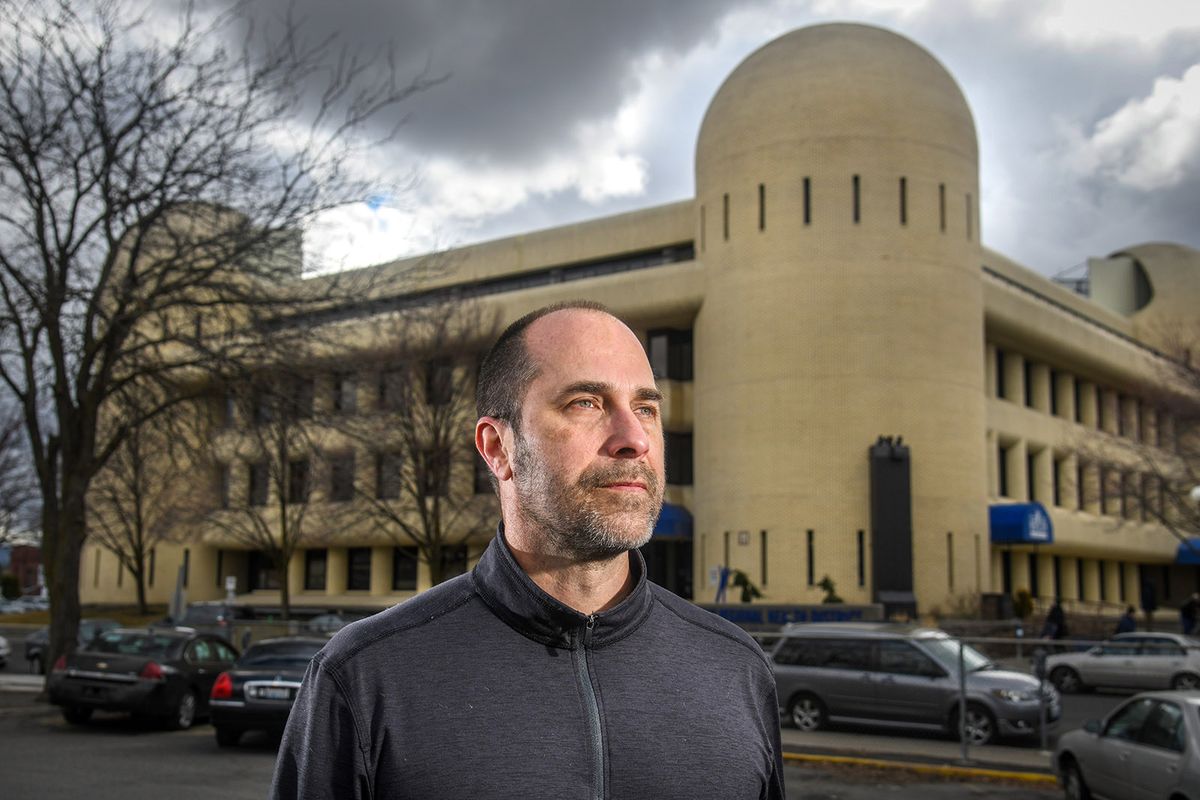

“We knew we weren’t going to be able to contain it,” said Mark Springer, a longtime epidemiologist at the Spokane Regional Health District.

COVID-19 arrived in March, in the midst of respiratory virus and flu season, and local health workers had their hands tied by stringent guidelines and federal lags in testing infrastructure.

“It’s a huge disgrace, what happened on the federal level in how testing rolled out,” Halloran said.

The district was forced to ration its limited testing supplies and use them only in accordance with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines.

“We essentially could only test people who traveled, but we now know it was circulating in our communities well before we identified those first cases,” she added.

Once testing was available, it was limited.

Patients being tested had to presume they were positive and quarantine at home, with test results taking a week or longer to come back. By the time a person learned their test results, they were practically through with quarantine.

By March, the Spokane community was accustomed to hearing or reading about the new virus, as Providence Sacred Heart Medical Center had accepted four cruise ship passengers with COVID-19 into its special pathogens unit.

But while those four passengers, who were in stable condition, were stuck in the hospital, repeatedly being tested for the virus, other positive cases were circulating in the community undetected.

On March 11, 2020, Lutz shut down a youth basketball tournament scheduled for the coming weekend and held a news conference with Spokane Mayor Nadine Woodward, urging social distancing. No one was wearing masks yet, but Lutz was confident the virus was in Spokane.

Epidemiologists had to come up with the proof.

Springer told The Spokesman-Review on March 6, 2020, that it was a matter of “when” not “if” the virus was here. And then, on March 14, the beginning of what has now been more than a year of maybe unprecedented – but certainly predicted – pandemic.

The year that followed brought suffering, depression and disappointment for many in the community.

For epidemiologists, accustomed to outbreaks and containing diseases, a full-blown pandemic has also tested their limits.

Springer, who has worked at the health district for 20 years, and the small but mighty epidemiology team quickly realized it needed more support, and would probably be unable to conduct case investigations if case counts increased. Several other health district staff shifted roles and helped with case investigations and contact tracing.

Eventually, each epidemiologist was overseeing a team of investigators, working with different industries or parts of the communities that needed to adhere to specific health guidance or take precautions against outbreaks. The district eventually hired more epidemiologists to grow the team.

The work was long and tiring. Springer said most epidemiologists were pulling 60 to 70 hours a week.

Epidemiologists at the district take weeklong shifts of being “on call” like Halloran was last March when she got the fateful call. Adding staff to their team, as well as hiring the Public Health Institute, was vital to the district’s ability to keep up.

In April, SRHD staff confirmed an average of seven cases per day. In July, the county averaged 78 cases per day. By December, the county averaged 280 new cases per day.

Springer and the team of epidemiologists had already started preparing for doubling, tripling and even quadrupling case loads in spring 2020. He said they were asking early on, “How do we scale up?” and, “What does it look like for the community to have 100, 200 or 300 cases confirmed in a day?”

“I think our leadership did a really good job bringing on additional staff when it looked like we didn’t exactly need it,” Springer said.

It took time to get people hired and in place, and they were just before the late fall and winter surge of cases, during a time when as many as 1,000 cases would be confirmed in just a few days.

As masking in public became the norm in Washington, cases and outbreaks were more often tied to family gatherings or social events among friends or sometimes workplaces, where people would let their guards down in break rooms.

“We saw a lot of transmission happening in a lot of personal communities with extended families, friends,” Springer said. “People would still have get-togethers and larger events.”

The idea that knowing someone meant they couldn’t give you COVID-19 sounds ridiculous, but that’s exactly how some people behaved – going to stores and doctor’s appointments with a mask on, but taking them off when gathering with friends and family members for a barbecue.

Asymptomatic spread of the virus made tracking COVID-19 even more challenging.

“If I had a nickel for every time people said it was congestion, allergies or it’s just a headache, I would be a rich person,” Springer said.

In late October, the health district was jolted to the spotlight of the crisis, not because of the work it was doing, but because Administrator Amelia Clark, and then the Spokane County Board of Health, fired Lutz.

There were protests outside of the district. The majority of unionized members submitted a vote of no confidence in Clark following the firing.

Some quit out of protest, including Halloran, who left in mid-December.

Others had to continue the daily grind, preparing for what would be the worst surge in cases yet.

The investment in staff paid off as the third wave of the virus statewide crushed the community.

During the winter, the district had more than 15 people internally working on cases, Springer said, in addition to the 40 to 60 employees with the Public Health Institute supporting the district staff.

Outbreaks escalated at dozens of long-term care facilities in Spokane County. Hospital beds filled, wings expanded. Political and public health leaders begged people to stay home and not gather for the holidays.

The winter surge, which escalated hospitalizations and deaths in Spokane County, meant long days for public health workers.

In a little longer than a year, 38,403 Spokane County residents have tested positive for COVID-19.

So far, 1,758 residents have been hospitalized with the virus, and more than 580 residents have died.

Vaccines are finally providing a much-needed reprieve, as are people continuing to social distance, limit gatherings and wear masks.

As case counts have plateaued, Springer and his colleagues can breathe a bit easier – although, by any means, the pandemic is not over.

So far this month , the district has confirmed a little more than 1,000 cases.

Springer said the plateau has been good for morale.

“As our numbers go down, we’re scaling up how aggressive our investigations are in terms of identifying close contacts and isolation – that part has been really encouraging,” he said.

Reflecting on her time at the district last year, Halloran said the team supported one another and, despite her personal burnout, she applauded her colleagues’ dedication and hard work in the midst of what was a chaotic and stressful year.

“If you go through a trauma together, it brings you together,” she said. “It was a complete team effort, and we took care of each other.”

For now, the race isn’t finished. Springer anticipates the spring to bring with it challenges of variants.

He said if community members can refrain from gathering, then perhaps outdoor alternatives for graduations or weddings can become a reality in the season.

Getting through March, April and May with vaccinations and a low incidence rate will help the community push forward for a potentially much more normal summer.

Springer thinks about this spring as the last couple miles of Bloomsday.

“We are close to the finish. We kind of went up our Doomsday Hill for Bloomsday, and we’re in the flats and it’s another mile to the finish line,” he said. “And I would hate people to say, ‘No I’m done with this.’ No, push through.”