One year later, here’s what we’ve learned about how a pandemic unfolds in Idaho

Protesters gather outside Central District Health’s office on Dec. 15 in Boise. (Otto Kitsinger)

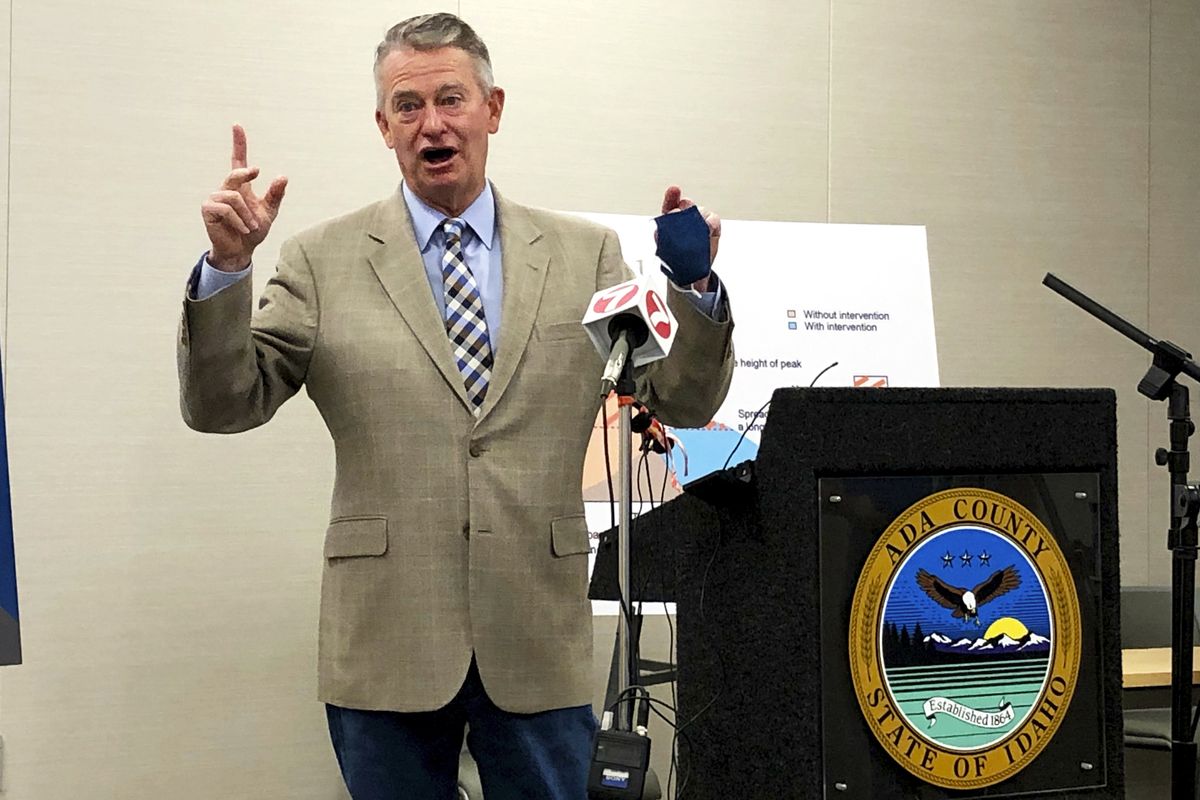

As the one-year anniversary of Idaho’s first reported case of COVID-19 approached, the Idaho Statesman asked Gov. Brad Little what he wished he’d known about how the pandemic would unfold in Idaho.

A couple big things stood out, he said.

First, the many weeks of backlogged unemployment claims took him by surprise.

“We were already besieged with a huge increase in unemployment as a result of the initial wave of layoffs because of the pandemic. And if I knew earlier what superstructure of state government I needed to beef up,” pandemic unemployment aid to Idahoans would have gone smoother, he said. “It was embarrassing.”

The second thing he didn’t anticipate: How skepticism, confusion and denial would damage efforts to control the pandemic. Little said he wished public messaging had been more clear that “it’s a novel coronavirus,” and that public health officials might change their predictions and guidance as they learned more about how the virus worked.

“Having that heart-to-heart with the people of Idaho, about the novel nature of it, and the necessity for everybody to choose to do the right thing, I wish I would have done that earlier,” he said.

Little announced the state’s first confirmed case of COVID-19 the afternoon of Friday, March 13, 2020.

As the year trudged on, a small but vocal group of Idahoans reacted to public health measures by staging protests at health board members’ homes or yelling, throwing food or agitating for fights at local businesses that required masks, according to previous Statesman reporting. But the pandemic brought stories of solidarity, as well. Health care providers that were competitors became allies and even shared precious vaccine doses with each other.

The past year brought surprises to even biosecurity experts who specialized in planning for pandemic response.

Yet, researchers warned for years of problems with a pandemic response.

The Trust for America’s Health and Robert Wood Johnson Foundation have issued reports for at least a decade that raised concerns about Idaho’s readiness for an emergency like infectious disease outbreaks. Idaho ranked lowest or among the lowest in the U.S. in recent years, according to the nonprofits that focus on health.

The state’s low flu vaccination rates for children and adults, and below-average scores in areas related to incident management and communication, were among the reasons listed in a 2014 report. Two years later, Idaho tied Alaska for lowest score, with the report noting a 31% drop in federal public health emergency and hospital preparedness grants.

Local public health agencies were charged with leading Idaho’s coronavirus ground war. But the agencies entered 2020 with depleted war chests, from years of federal and state funding cuts.

For the past 15 years, state lawmakers cut Boise-based Central District Health support. CDH went from receiving state appopriations of $25.38 per capita in fiscal year 2005, to $18.49 per capita in fiscal year 2020, based on a Statesman analysis of budget records and U.S. Census population data for the counties in CDH.

1. The coronavirus was here before anyone tested positive, so were variants

Little held two press conferences at the Capitol on March 13, 2020. That morning, he announced a public health emergency; while Idaho was one of two states without a COVID-19 case, public health officials believed it was just a matter of time. It turned out it was a matter of hours, because he called journalists and health officials back that afternoon to announce the first confirmed case of COVID-19 – in a woman from Ada County who had recently traveled to New York City.

At the time, though, the entire U.S. was hamstrung by a slow rollout of coronavirus tests. The few tests Idaho could secure went to the people most likely to have the virus – those who had symptoms and had traveled to hot spots.

That night, the Statesman sent state public information officers an email.

“The governor stressed that the case announced today was traceable to a confirmed case in another state, and that made it less worrisome than a community transmission,” the email said. “But the testing being done in Idaho is limited to cases like that … linked to travel/contact out of state. From everything I’ve heard, few (no?) tests are being done that could catch a local community transmission, because the testing guidelines don’t allow for that. It seems like this creates a false sense of security – not finding community transmission because you can’t. Can you tell me if I’m wrong? Would the woman who received the test have gotten one, if she didn’t know she’d had contact with the confirmed case in NYC?”

The spokespeople didn’t respond, but it soon became clear that every state was in that same boat. The nation’s scarce testing resources made it next to impossible to stop “community transmission” through testing, tracing and isolation.

Health care providers had limited tests. So they had to choose carefully. The state lab told them to focus on patients most likely to test positive – which, at the time, didn’t include people who caught it at the grocery store, or whose symptoms of headache, diarrhea or loss of smell weren’t yet on the COVID-19 red-flag list.

By the time Idaho announced its first official COVID-19 patient, there were actually hundreds in the state. More than 200 other Idahoans were sick with COVID-19 by March 13 and would eventually test positive or be tallied as “probable” cases.

Later in March, the governor issued a stay-home order. It slowed transmission enough for testing capacity to grow. A year later, testing has caught up to cases, and Idaho recently hit a mark of adequate testing: less than 5% of tests coming back positive.

While COVID-19 tests caught up with Idaho’s infection rates, the new year ushered in a new blind spot: highly contagious variants of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. The only way to detect variants in a community is through sequencing the virus in a lab.

Idaho, like the rest of the U.S., wasn’t doing much of that early this year. There was no national plan to look for variants until last month.

The Idaho Department of Health and Welfare announced Feb. 24 the first cases of variant infections in Southwest Idaho.

A week earlier, though, health officials said they’d found evidence of two different variants in the Boise area. Who was infected? Nobody knows. But local residents were shedding enough of the mutant virus to make it detectable in wastewater.

Now, in mid-March, labs are still limited but have been ramping up sequencing efforts. Idaho has sequenced 363 samples of the coronavirus as of this week, finding 22 cases of people infected with a total of three troublesome variants, according to state data.

2. Public health board members didn’t believe public health experts

Idahoans got a free education in public health decision-making processes at the local level in Idaho.

For the past year, board members who oversee Idaho’s seven regional health districts have questioned the truth about COVID-19, have doubted firsthand accounts from physicians, have shown up to meetings without face coverings and ignored social distancing advice.

The Southwest District Health board met in November to hear from St. Luke’s Health System epidemiology and infectious disease doctors.

They also heard from two local practitioners who shared misinformation and popular internet conspiracy theories.

Idaho is “a victim of a very sophisticated psy-ops, psychological warfare,” Dr. Vicki Wooll told the board. “It’s getting us through social media. We are not the enemy. The enemy is coming from without.”

In a lengthy presentation, Wooll claimed that 5G wireless internet may be tied to COVID-19 – a false theory that was spread on social media – and shared other debunked ideas.

Michael Karlfeldt, an unlicensed naturopath from Meridian, repeated disproven claims about masks, among other things. Karlfeldt said there is no benefit to wearing masks in public and that masks are harmful, “increasing the concentration” of coronavirus particles.

The speakers who followed their presentations were Dr. Sky Blue, a St. Luke’s infectious disease specialist, and Dr. Michaela Schulte, a hospital physician who also specializes in infectious disease. They talked about the coronavirus, how to prevent transmission, how vaccine trials work and what they were seeing in the hospitals where they worked.

After the meeting, the Idaho Statesman asked Southwest District Health how the speakers were chosen. The district’s spokesperson said the board – which is separate from the public health district’s epidemiologists and staff – had invited them.

Katrina Williams, the spokesperson, also offered a statement.

“In addition to the usual board business, the board members had requested to include guest speakers who presented both conventional and non-conventional viewpoints of COVID-19,” Williams wrote. “The viewpoints expressed by the Board of Health members and guest speakers are not necessarily representative of the views of the Southwest District Health organization.”

The board is made up of several elected officials from the counties that comprise the district.

Adams County Commissioner Viki Purdy, who sits on the board, told the Statesman in an email that she invited Karlfeldt and Wooll.

“I made phone calls to (Karlfeldt) and Dr. Wooll to invite them to speak and called again when the speaking times were set,” Purdy wrote. “The reason for inviting doctors outside of the St. Luke’s system was to get more information to citizens to protect their own health. No one has brought to the citizens the need to boost vitamins we may be deficient in that would keep us healthy. That’s just one example.”

In emails provided to the Statesman under a public records request, Purdy said she wanted to “spend the entire meeting learning from” Wooll and Karlfeldt, instead of infectious disease specialists.

“We hear from the St. Luke’s doctors daily,” Purdy wrote in a late-October email to the board and health district officials. “We don’t represent St. Luke’s and we cannot give them a private platform. … I can’t think of a better platform than we can provide to hear all the medical points of view and concerns. Science provides us with a lot of information. We will certainly have a more balanced view, which I am sure the public will appreciate. As I have said, no one ever speaks about how we can all improve our immune system, there are so many questions people have that they are not getting answers to.”

After comments that illustrated a lack of understanding about local hospitals – such as the type of medical care they provide, whom they serve and their ownership structures – Purdy wrote: “My point is that why aren’t we encouraging competition and helping facilitate more private hospitals? This is about far more than this virus. It’s about the capabilities of the system and the control they want to exercise.”

3. Idaho hospitals, clinics still had PPE shortages nine months later

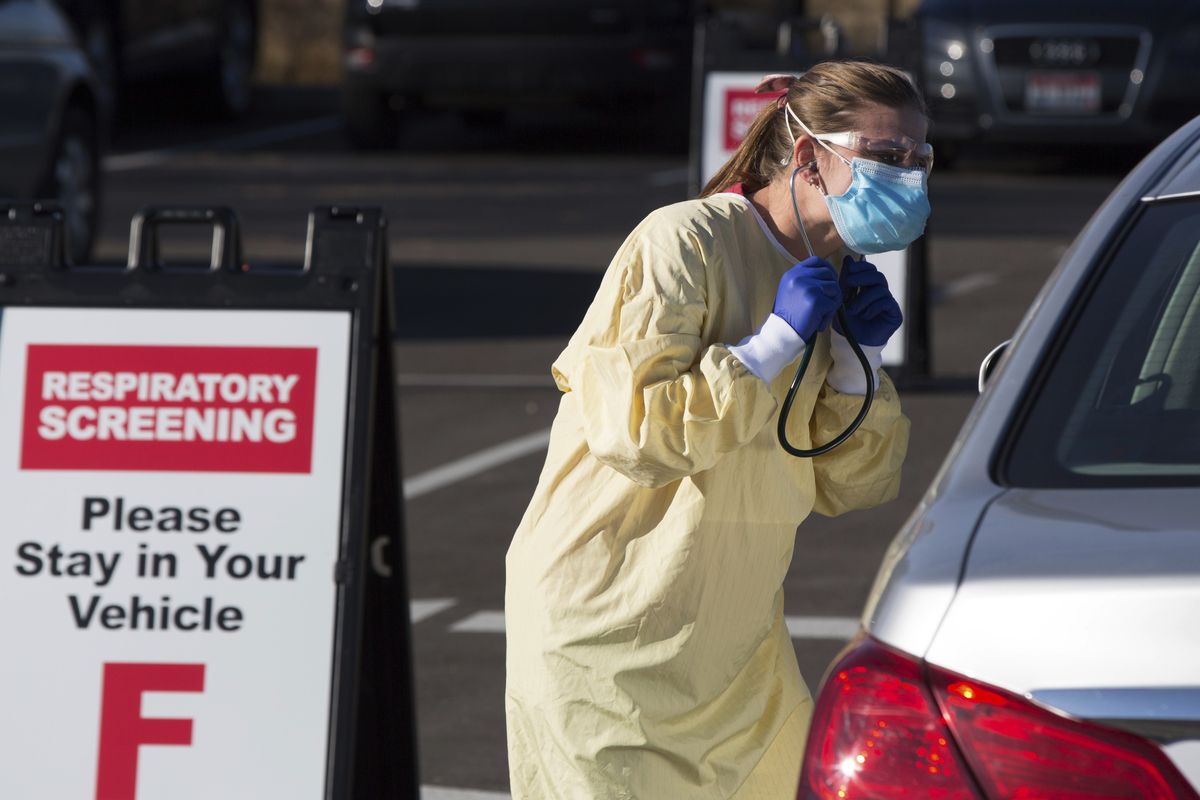

Nurses and doctors around the country were speaking out last spring about the shortages of N95 masks, surgical masks, gowns, face shields and other personal protective equipment.

The N95 shortage was a crisis of its own. Those respirators had enough filtration to protect health care workers from tiny coronavirus particles in the air. But in a normal year, they weren’t a constant necessity.

Health care workers on the front lines told the Idaho Statesman last spring that they had to reuse N95s and that employers were limiting their access to them. One doctor said in March 2020 that she was fired after she insisted on an N95 and brought her own to work.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration issued guidance for the crisis that said it was permissible to reuse N95s, for example.

The PPE shortages stopped making headlines. But they continued – from spring into summer, fall and winter.

Last summer, the Statesman obtained a notice that Saint Alphonsus Health System issued to personnel, with a “reminder” to reuse N95 masks “until soiled, torn, or difficult to breathe through (or unable to obtain a fit seal).”

The health system also told staff that OSHA required all PPE to be provided by and paid for by Saint Alphonsus, so employees couldn’t bring in their own.

“There continues to be worldwide supply chain issues in obtaining masks,” Saint Alphonsus Health System spokesman Mark Snider said in an email to the Statesman in December.

“We are following CDC and OSHA recommendations for conserving N95 masks and have sufficient supplies,” Snider said. “The guidance on N95 usage has not changed since the beginning of the pandemic. Additionally, we are introducing more permanent respirator options, reducing the use of disposable masks in our COVID-19 units.”

While some nurses around the state reported having a more relaxed supply of masks at times, many health care workers who spoke with the Statesman described a “new normal” of rolling supply shortages. One month, the N95s would be in low supply. The next month, gloves or gowns.

Hospital officials with the St. Mary’s and Clearwater Valley Hospital and Clinics in North Central Idaho described trying to afford the PPE during a pandemic.

“More PPE would be welcome,” said Chief Medical Officer Kelly McGrath, in a December 2020 interview. The Cottonwood and Orofino health facilities, like others around the state and country, still had to reuse N95s.

But at that moment, the challenge was gowns. The disposable ones, so easy and quick, had spiked in price.

“The laundered (cloth) ones are less than $1 per use, and the disposable are up to $6 per use,” McGrath said.

“I just feel fortunate that when it first started, with our burn rate, we had a few times we had three days of supply available, and that was stressful because I worried our staff would be put at risk,” he said. “If you’re used to a bad situation, and it’s not quite as bad (anymore), it feels better.”

He wondered aloud how, in the country with the most health care resources and consumption in the world, a hospital would struggle to find “something as simple as a procedural mask or an N95. … We don’t have basic items.”

It wasn’t just PPE, either. Health care facilities in different regions of Idaho reported getting rapid-test machines through a federal program, but couldn’t get their hands on enough supplies to do rapid testing in an effective way.

One small hospital in Minidoka County was still having problems getting COVID-19 test kits in November.

Hospitals and clinics ran low on people, as COVID-19 outbreaks affected their staff or their staff’s family members. During the fall and winter surge in COVID-19 hospitalizations, small hospitals like St. Mary’s and Clearwater Valley could go from fully staffed to drastically understaffed in a matter of a day.

“We have 12 (registered nurses) that cover our hospital, and if two of them are out, those are two shifts that are uncovered,” President and CEO Lenne Bonner said in a December interview.

Bonner said they considered hiring a travel nurse to help. But it was getting harder to find willing nurses at a price they could afford, she said.

“The last traveler we looked (at hiring) was $6,000 a week,” she said. “If you have to, you have to, right? And that’s why they’re so expensive.”