We the People: 14th Amendment defined citizenship

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: What amendment gives citizenship to all persons born in the United States?

The amendment that gives citizenship to all persons born in the United States is the 14th Amendment. Adopted in 1868, Section 1, Clause 1, of this amendment guarantees that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.”

Except for children born to foreign diplomats under the jurisdiction of the U.S., this means that all individuals born or naturalized within the boundaries of the United States or born to American citizens abroad are citizens of the country. While the Citizenship Clause of this amendment seems straightforward, there are important details regarding the background of this clause, citizenship linked rights, and the extension of these citizenship linked rights that merit further examination.

The Citizenship Clause is a codification of the principle of birthright citizenship. For the United States, birthright citizenship was not conceived of in a vacuum but rather was inherited – like several parts of the U.S. constitutional framework – from the British government. Before 1776, all individuals born within the British Empire were considered British citizens, including those in the North American colonies of the empire that later became the first 13 American states.

In fact, a common assumption among American government luminaries of the late 18th century – including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson – was that rights linked to British citizenship ought to be the same for citizens anywhere in the empire.

When some American colonists began to see more sizable gaps between their rights as British citizens and those in other regions of the empire, such as with the issue of “no taxation without representation,” they initially considered and later resolved to separate from Great Britain during the First and Second Continental Congresses in 1774 and 1775.

When the United States become independent on July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence read in part that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Even though the United States kept the practice of birthright citizenship from Great Britain, the constructors of the American government thought the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness would be more securely and equally provided for in the United States when linked to American citizenship.

Although the word “citizen” is present in the original U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights (ratified in 1788 and 1791), in the late 18th century there was no precise definition of American citizenship.

According to Martha Jones in her “Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America,” before 1868 citizenship was both imprecisely defined and predicated on race:

The Constitution’s only references to citizens were fragmentary and implicit: Only citizens could serve as members of Congress; only “natural born” citizens as president; only citizens could sue in federal courts. The Constitution thus guaranteed privileges and immunities of citizens but did not delineate how to distinguish citizens from noncitizens. Additionally, the matter of race and citizenship, in both state and federal terms, remained unsettled.

Privileges and immunities refer to rights connected to U.S. citizenship. Before the American Civil War, these included rights such as the right to labor, freely practice one’s religious beliefs, have the right to a jury trial in criminal law cases, travel within and between states, and more.

During this time in U.S. history, however, federal civil liberties protections (a civil liberty is an individual right protected against government intrusion) in the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights (the first ten amendments) only applied to the actions and laws of the federal government, not to those of state governments.

This meant that different sets of rights were linked to state citizenship versus federal citizenship. For example, into the early 19th century, several states still had a government endorsed religion, which today would be considered a violation of one’s religious rights. Before 1868, though, states had wide discretion in deciding whether to recognize the rights and liberties linked to federal citizenship.

This changed with the American Civil War. The war created the policy window that made the adoption of the 13th (prohibiting slavery, adopted 1865), 14th and 15th Amendments (right to vote regardless of race, adopted 1870) more likely.

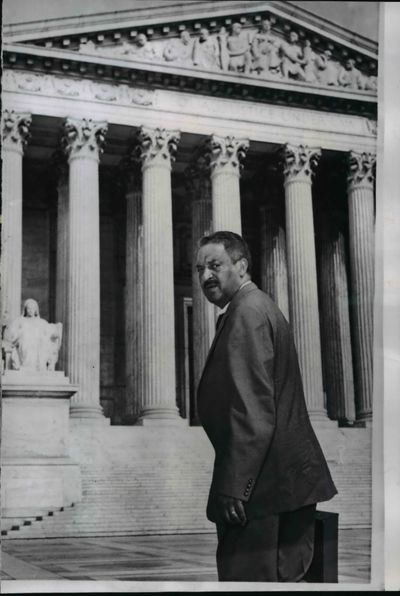

The racialized debates surrounding slavery and citizenship from 1776 to the eve of the war also made the adoption of these amendments – according to former Supreme Court Justices William Brennen and Thurgood Marshall – necessary to improve the U.S. Constitution.

Although the contours of American citizenship were not precisely defined before 1868, federal laws such as the Naturalization Act of 1790 and Missouri Compromise of 1820 as well as Supreme Court decisions such as Dred Scott v. Sandford from 1857 largely limited federal citizenship and linked rights to non-Hispanic whites and excluded African Americans, Native Americans and other racial minorities.

The implications of this were dire. For example, if a free African American were captured in antebellum America by a slave catcher, they might allege that the free African American was a slave and therefore subject to fugitive slave laws. Free African Americans, however, would not have the ability to challenge the allegation in court because they lacked federal citizenship and linked criminal justice rights.

Regarding citizenship, the 14th Amendment was adopted most directly to protect the rights of African Americans, but the implications extend to all those born or naturalized within the U.S. A debate surrounding the Citizenship Clause of the 14th Amendment, from 1868 to today, regards what privileges and immunities of federal citizenship must be recognized by state governments.

While today most federal constitutional rights are considered parts of federal citizenship that belong to all Americans regardless of where they reside, the American government – through a process known as incorporation – still has yet to make several federal rights protections (such as parts of the Fifth and Sixth Amendments) fully applicable to state governments. Although the 14th Amendment more precisely defined federal citizenship in the U.S., the contours of federal citizenship still are being shaped today.

Michael Ritter is assistant professor of political science at Washington State University in Pullman. This article is part of a Spokesman Review partnership with the Foley Institute of Public Policy and Public Service at Washington State University.