Atlanta’s unexpected civil rights museum: Its Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport

Walking through the Atlanta airport, I hear a powerful voice calling out over the bustle. “The world is waiting for you,” it proclaims. The passengers surrounding me continue their march past Burger King and toward security.

But I stop and turn, searching for the source. “The world would like you to find a way, to get in the way,” it continues with a preacher’s cadence, “to get into what I call good trouble, necessary trouble.” Not your typical preflight announcement, but the messenger isn’t an airport employee, either.

I round the corner to find John Lewis calling to me from a video monitor. Surrounding him in the domestic terminal atrium are display cases holding artifacts and mementos that document his extraordinary life.

Lewis was a onetime Freedom Rider who led lunch-counter sit-ins, suffered a fractured skull after an attack during a civil rights march near Selma, Alabama, and served 17 terms in Washington, D.C., as a Democratic representative for Georgia’s 5th District, which includes most of Atlanta.

The exhibit complements a departure gate display devoted to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., which includes objects such as the transistor radio he carried to marches to monitor news coverage.

And near the airport train, an extensive walkway exhibit shows how Atlanta’s Black community fought segregation. Taken together, the exhibits at Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International, one of the world’s busiest airports, offer visitors an unexpected dive into civil rights history.

For passengers, it’s certainly a more rewarding way to spend a layover than lining up for an overpriced sandwich. And although airport officials like to say that the ATL sees more people in a month than Paris’ Louvre welcomes in a year, there never seems to be a crowd at the exhibits.

Although it might seem surprising to find artifacts at an airport, Benjamin Austin, Hartsfield-Jackson’s senior art program manager, says these transportation hubs are “the most public, diverse and democratic settings available.”

“There are many people in the world who do not have the opportunity or inclination to visit institutions such as the King Center or Smithsonian,” he says. The displays provide “a unique opportunity that not even the greatest museums in the world enjoy: the ability to reach an audience … that does not intentionally seek out such experiences.”

Because there are many other traditional exhibits devoted to King, those who want to learn about the leader aren’t forced to come to the airport. But the Lewis display and artifacts make up one of the most extensive exhibits about him.

Tom Houck, who served as a driver and personal assistant to King and now runs Civil Rights Tours Atlanta, is a big fan of the displays. “I’m for doing everything possible to put our African American civil rights history in front of everyone’s eyes.” And, he adds, the displays are particularly appropriate, given that the airport’s name partially honors the city’s first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson.

So, after clearing security, I pull my rolling suitcase past an InMotion electronics and headphone store to take a look at “Legacy of a Dream,” the free-standing King display at the top of the escalators in concourse E.

The display, which includes artifacts on loan from the King Center for Nonviolent Social Change and the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, was installed in the 1980s. It offers a window into the leader’s personality, insecurities and struggles.

Family pictures show the famed minister at age 2. The text notes that he felt the sting of racism just a few years later when the mother of two white boys wouldn’t let them play together.

Other photographs offer glimpses of upper-class Black life in Jim Crow Atlanta: a family portrait with a 10-year-old King in a suit and tie; college graduation with his sister; and his wedding day with Coretta Scott. The future preacher, we learn, discussed marriage on their first date. Later, we see King playing with his children as well as presiding over a family dinner with a picture of Mahatma Gandhi hanging over the doorway.

There are some surprises. A kiosk shows King’s reading glasses, noting that although he didn’t need them, he felt they made him look distinguished. The minister, you can sense, felt the enormous burden of his role in his lifetime. The exhibit includes a draft of his 1959 resignation letter from Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, where he met Rosa Parks and led the bus boycott.

“At points, I was unprepared for the symbolic role that history had thrust upon me,” he wrote to his congregation. “Little did I know … a movement … would change the course of my life forever.”

A candid airport waiting room photograph shows King and aide Andrew Young, who would become U.S. ambassador to the United Nations. Both men look tired but determined.

Artifacts include a permit, program and protest sign from the 1963 March on Washington; a suit worn by King when he met with President Lyndon Johnson to discuss the Voting Rights Act; and a funeral photograph of a mule-drawn cart carrying his casket.

Before leaving, I took note of the 10-foot wall tapestry by Czech artist Peter Sis. It was sponsored by U2 members Bono and the Edge along with former Police frontman Sting.

The handmade artwork, showing a silhouette of a robed King, recalls his speech at Washington’s Lincoln Memorial during the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom. King’s “Give Us the Ballot” address was the “I Have a Dream” of its day, helping cement his national profile.

Meanwhile, as airport visitors can learn as they make their way down the corridor between concourses B and C, Atlanta was facing its own struggle with civil rights.

Presented sequentially, a more than 400-foot-long display titled “A Walk Through Atlanta History” fills two walls with a mosaic of graphics, videos and photos. Most passengers, gliding by on moving sidewalks, pass it in a blur.

Step off the treadmill, and you’ll find a mini city museum starting at 11,000 B.C. and ending with Atlanta’s appearance on the global stage as host of the 1996 Summer Olympics. Although heavy on boosterism, the exhibits don’t ignore reality. During the mid-20th century, Atlanta cultivated its reputation as the “city too busy to hate.” The story is more complicated.

Photographs show a voting registration drive in the 1940s and an NAACP protest sign: “12 other Southern cities have open hotels, why not Atlanta?” Another display notes how the Georgia legislature refused to swear in duly elected civil rights activist Julian Bond, and we also see a banquet celebrating King’s 1964 Nobel Peace Prize – one of the first times Atlanta’s white establishment honored its native son.

But of all the displays, the Lewis exhibit, dedicated in 2019 a year before his death, feels most personal. He worked with exhibit designers and lent objects for display. During the dedication of the tribute wall, the congressman noted that he spent plenty of time at Hartsfield-Jackson. “Sometimes I feel like I should have maybe a condo, maybe an apartment, a house here at the airport. I feel like I live here.”

When I pass through the airport a week later, I build in extra time to visit. Separate cases labeled “Preacher,” “Activist,” “Public Servant” and “Visionary” take us from his childhood on a tenant farm in Troy, Alabama, to national prominence.

The journey starts with chicken figurines. As a child, the man who was called the “conscience of Congress” hoped to become a minister, and during nightly feeds he would preach to an audience of chickens. Throughout his life, chickens reminded Lewis of his roots.

The 24-foot painting above the cases, titled “The Hero’s Journey,” captures key moments from Lewis’ life, from the cotton fields of his youth to his more than 50 honorary degrees. The art is framed by riveted metal, evoking Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, where Lewis was beaten on Bloody Sunday, and it’s surrounded by charred wood. The fire-tempered material, we’re told, represents the inner strength of protesters and also the farmhouse where Lewis was raised.

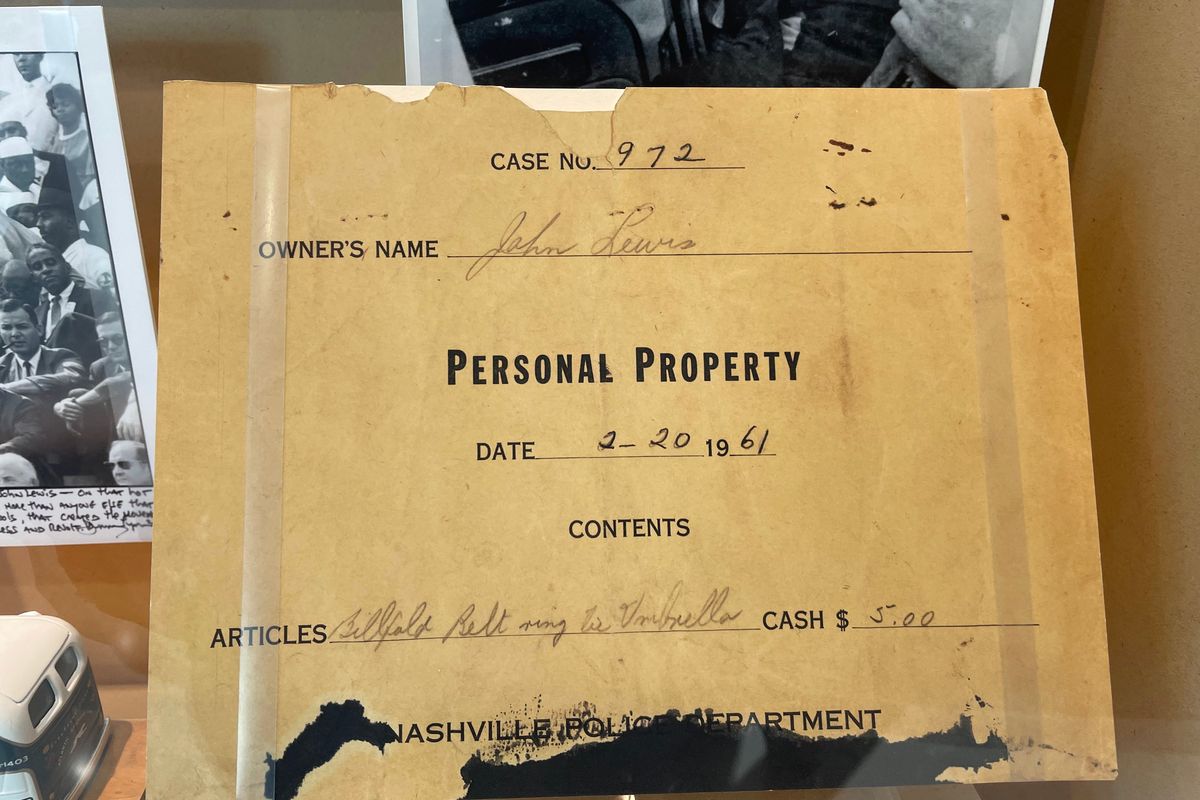

Other artifacts include an arrest file from Nashville; a John Lewis action figure; and his Presidential Medal of Freedom. In the bottom corner of the last case, I notice the signed envelope from the 2009 inauguration when the nation’s first Black president acknowledged his debt to the civil rights leader who preceded him. “Because of you, John,” reads the note from Barack Obama.

Too soon, it’s time to go. As a chorus of “We Shall Overcome” rings out from a looping video, Lewis offers his parting words. “In the ’60s, I got arrested a few times, 40 times, and since I’ve been in Congress, another five times,” he says.

“My philosophy is very simple: When you see something that’s not right, not fair, not just, stand up, say something, speak up and speak out.”

I turn to join the stream of passengers flowing toward security, then to my flight. As Lewis has promised, the world awaits all of us.

INFO: Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, 6000 N. Terminal Parkway, Atlanta; (800) 897-1910; atl.com