Tropical storm could form in Atlantic next week and threaten Caribbean

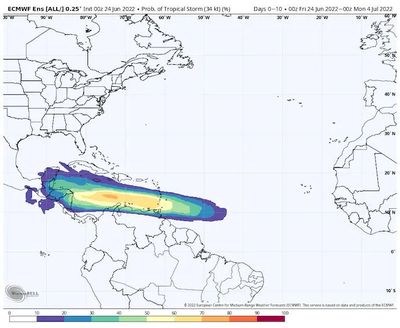

Atlantic hurricane season officially starts June 1 but doesn’t usually ramp up until July or August. But an unusually early tropical storm has a strong chance to develop next week in the “main development region” of the tropical Atlantic. The potential storm is already of interest to the Windward Islands, which mark the divide between the Atlantic and the Caribbean.

The system isn’t a tropical depression yet, but it’s in an environment that favors organization. Weather models are bullish on its prospects of development, and overall steering currents would take it west toward the Caribbean.

It’s not yet known to what extent it will intensify, but it’s worth keeping close tabs on it as it evolves over the coming days. If it organizes and attains sustained winds of at least 39 mph, it will be named Tropical Storm Bonnie.

The National Hurricane Center in Miami estimates a 60% chance of eventual development, writing: “A tropical depression could form during the early to middle part of next week … and approaches the windward islands.” Thereafter, the system should wind up somewhere in the Caribbean. Eventually, it could affect Central America.

As it stands, experts have unanimously predicted an active or hyperactive hurricane season, the anticipated effects of a lingering La Niña coupling with anomalously warm sea surface temperatures.

The system is a mere cluster of showers and thunderstorms about 600 miles south-southwest of the Azores. Downpour activity is more prevalent on the northern half of the system.

That’s also where signs are beginning to manifest of loosely organized outflow, or air exiting the storm at high altitudes. Tropical cyclones are, in essence, heat engines – they ingest warm, humid air in contact with the bath-like sea surface at the low levels, and exhale “spent” air aloft. The more efficiently a system can evacuate already-processed air from above, the easier it is to draw in more moisture-laden air from below and intensify.

In the coming days, the nascent system will meander west through a relative minimum in wind shear, or a change of wind speed and/or direction with height. Wind shear can be pernicious and disruptive to a tropical system, knocking it off-kilter and inhibiting its organization. The lack of wind shear is a window of opportunity. It remains to be seen to what extent the clumping of downpours can take advantage of improving environmental conditions in the days ahead.

From its current perch in the eastern tropical Atlantic, the system should continue almost due west, with little to interrupt its motion.

Weather models suggest it will remain a diffuse area of spin before consolidating sometime in the Monday to Wednesday time-frame, potentially on final approach to the Windward Islands.

The system probably won’t have enough time to intensify dramatically before affecting the islands, but heavy rain and some localized flooding would be probable in the midweek period.

There’s an outside chance that the system could strengthen to become a high-end tropical storm or low-end hurricane and unleash strong to damaging winds, torrential rain and an ocean surge.

Thereafter, it’s probable that the system would continue its westward journey into the Caribbean. That’s around the time when shear looks to fall off markedly, potentially promoting intensification.

Sea surface temperatures are acutely above average in the eastern Caribbean, but near to slightly below average in the western Caribbean. Still, areawide they’re at or above the roughly 82 degree threshold needed to support the growth and maturation of a tropical cyclone.

Nicaragua and Honduras ought to pay close attention to what transpires with this system, but any possible arrival of inclement conditions wouldn’t occur until the beginning of July. There’s also a slight chance that the system gets pulled north toward the Dominican Republic and Haiti after passing the Windward Islands. In that case, Florida and the Southeast United States. would need to pay attention to the system.

Assuming Bonnie forms in the “main development region” of the tropical Atlantic – which stretches through roughly the eastern two-thirds of the tropical North Atlantic several degrees north of the equator – it would be unusually early. Only three storms have formed in this zone during June previously, according to Phil Klotzbach, a tropical weather expert at Colorado State University. June tropical storms more typically form in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

Last year, Tropical Storm Elsa formed near the main development region on July 1 – farther east than only one previous storm so early in the hurricane season. Eric Blake, a forecaster at the National Hurricane Center, posted a tweet showing eerie similarities between forecasts for last year’s Elsa and what could become Bonnie this year.

However, while Elsa was dragged north and eventually barreled up the East Coast, what may become Bonnie has a better chance to take a more southerly track toward Central America.

Elsa was a harbinger of a very active Atlantic season that featured 21 named storms, the third most on record. Should Bonnie form, it could portend something similar for 2022.

“[T]he warmth in the Atlantic continues to rise and as of this week, the Main Development Region is the 7th warmest on record going back 40 years – behind some very active hurricane seasons like 2010, 2005, 2020, and 2011,” wrote Michael Lowry, tropical weather specialist for Miami television affiliate WPLG, in a newsletter. “The combination of the thermodynamic profile (the water temperatures) and conducive dynamics (lower wind shear) of the region are two big supportive factors in development ahead.”