We The People: The noble life of James Forten, a Black man inspired by the Declaration of Independence

Each week, The Spokesman-Review examines one question from the Naturalization Test immigrants must pass to become United States citizens.

Today’s question: What founding document said the American colonies were free from Britain?

On Sept. 8, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was first read publicly in Philadelphia. A boy who attended the reading was so inspired by the words to not only join the fight, but to expand America’s core ideals to all its citizens.

James Forten was a free man of African descent born on Sept. 2, 1766, in Philadelphia. A small percentage of Black citizens were free in the colonies during the Revolution. Both of Forten’s parents were free when he was born, and they managed to afford some formal education for their son. However, in 1773, Forten’s father died, forcing him to quit school and begin working to help support the family.

“His experience of hearing the Declaration of Independence read in Philadelphia led to him encouraging the United States to further commit to those ideas of liberty and quality,” said Matthew Skic, the curator of exhibitions at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia.

At 14, Forten began serving in the Revolution on the American privateer ship ”Royal Louis,” captained by Stephen Decatur. The Royal Louis sailed around the continental U.S. and captured British vessels, one of the few ways for the poor Continental army to gain new ships for their navy. Privateer ships are privately owned but given authority by a government to attack an enemy vessel during a time of war.

People of African descent played a prominent role in the Revolutionary War. Around 20,000 fought for the British , and 5,000-8,000 fought in the Continental Army. The Royal Louis featured dozens of African Americans on its crew. These men took an exceptional risk, because if they were captured by the British, there was a significant chance they’d be sold as slaves, Skic said.

During their first voyage, the crew members of the Royal Louis captured several British ships and brought them back to Philadelphia. However, on their second voyage, they were captured off the coast of Virginia and brought to New York Harbor by the British.

“Forten took a great risk for his country at a young age, which showed courage and boldness,” Skic said.

Captured soldiers were brought aboard prison ships in New York. Conditions in these prison ships were notoriously poor, with Forten being stationed aboard the “Jersey,” which had a reputation as perhaps the worst . He spent seven months on the vessel, which nearly killed him.

One of Forten’s most noble acts during the war took place on the Jersey. The British had made arrangements with America for a soldier exchange. Forten had an opportunity to escape inside the U.S. soldier’s wooden trunk.

He was only 14 and would easily fit in the trunk and escape. However, another young soldier aboard the vessel had fallen ill. Forten gave up his opportunity and let Daniel Brewton take his place. Brewton never forgot the favor, and the two remained friends throughout their lives.

Forten was freed in 1782, a year before the Revolutionary War ended, and he walked from New York to Philadelphia. When he returned home, it was a pleasant surprise for his mother and sister. They had assumed that he died as a result of his military service.

Following his service in the Continental navy, Forten became the leading sailmaker in Philadelphia in 1798. He became well known for making high-quality sails for merchant and naval ships, Skic said.

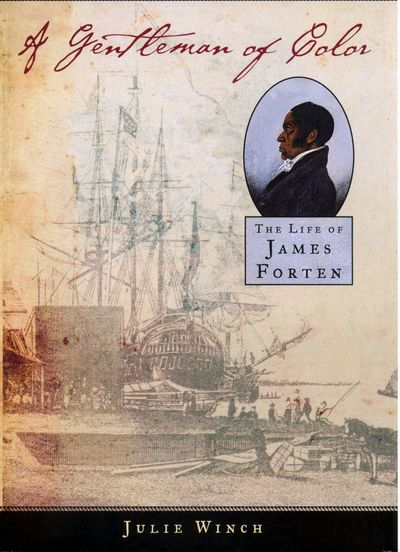

He used his earnings to support his beliefs, said Julie Winch, a history professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston and author of Forten’s biography, which was published in 2003.

“A lot of the money he accumulated went towards advancing his vision for America, which is a nation without slavery and a nation committed to equality of opportunity,” said Winch.

Forten raised his children to push for abolition and fight for the rights of his people.

“He campaigned for both the abolition of slavery and the abolition of laws and practices that make people unequal,” Winch said.

He was proud to be a veteran of the Revolution and was bothered by the fact that Black soldiers were not welcome in the street parades in Philadelphia on the Fourth of July.

During the Civil War, the Forten family supported the Union and recruited for the 43rd Regiment of the United States Colored Infantry organized in Philadelphia. One of Forten’s sons, Robert Forten, served in this regiment and was appointed its sergeant major, taking a senior role in leading the regiment.

James Forten died in 1842, still more than two decades before his hopes of abolition would be acknowledged nationwide.

Forten’s used his substantial wealth during his later years to help found The Liberator, published by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. The paper served as a community news board for the issue of slavery in the United States. It was a controversial paper for the time, not only for its fervent support of abolitionism but its advocacy for women’s rights.

The newspaper was in circulation until 1865 and inspired Frederick Douglass, a freed slave and abolitionist whose autobiography became a major work of American literature. The paper was banned in Southern states, with cash rewards offered to those who distributed it . The final edition ran in February 1865, shortly after Congress passed the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery. It chronicled several testimonies from generals and was filled with letters from African American readers rejoicing for their freedom.

The Museum of the American Revolution opened an exhibit earlier this year covering 100 years and three generations of the Forten family in Philadelphia. The exhibit, which closes in November, includes some of Forten’s writings, written records of his business and furniture from his home that was passed down through generations and donated by his descendants.

“The big thing is, he wants America to cleanse itself of slaveholding,” Winch added. “He sees slavery as not just a southern issue but a national concern.”