An AI supercomputer whirs to life, powered by giant computer chips

SANTA CLARA, Calif. – Inside a cavernous room this week in a one-story building in Santa Clara, California, 6½-foot-tall machines whirred behind white cabinets. The machines made up a new supercomputer that had become operational just last month.

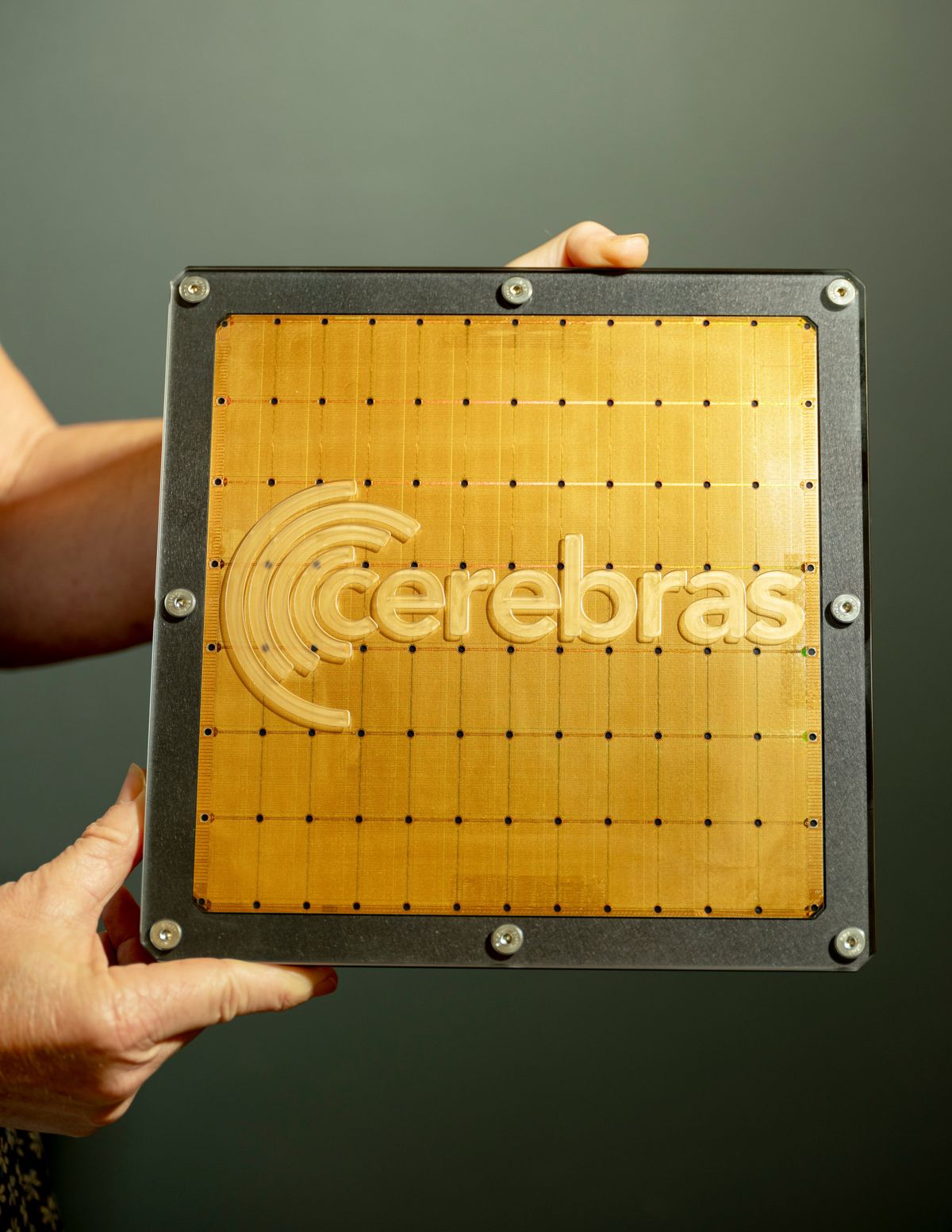

The supercomputer, which was unveiled earlier this week by Cerebras, a Silicon Valley startup, was built with the company’s specialized chips, which are designed to power artificial intelligence products. The chips stand out for their size – like that of a dinner plate, or 56 times as large as a chip commonly used for AI. Each Cerebras chip packs the computing power of hundreds of traditional chips.

Cerebras said it had built the supercomputer for G42, an AI company. G42 said it planned to use the supercomputer to create and power AI products for the Middle East.

“What we’re showing here is that there is an opportunity to build a very large, dedicated AI supercomputer,” said Andrew Feldman, CEO of Cerebras. He added that his startup wanted “to show the world that this work can be done faster, it can be done with less energy, it can be done for lower cost.”

Demand for computing power and AI chips has skyrocketed this year, fueled by a worldwide AI boom. Tech giants such as Microsoft, Meta and Google, as well as myriad startups, have rushed to roll out AI products in recent months after the AI-powered ChatGPT chatbot went viral for the eerily humanlike prose it could generate.

But making AI products typically requires significant amounts of computing power and specialized chips, leading to a ferocious hunt for more of those technologies. In May, Nvidia, the leading maker of chips used to power AI systems, said appetite for its products – known as graphics processing units, or GPUs – was so strong that its quarterly sales would be more than 50% above Wall Street estimates. The forecast sent Nvidia’s market value soaring above $1 trillion.

“For the first time, we’re seeing a huge jump in the computer requirements” because of AI technologies, said Ronen Dar, a founder of Run:AI, a startup in Tel Aviv, Israel, that helps companies develop AI models. That has “created a huge demand” for specialized chips, he added, and companies have “rushed to secure access” to them.

To get their hands on enough AI chips, some of the biggest tech companies – including Google, Amazon, Advanced Micro Devices and Intel – have developed their own alternatives. Startups such as Cerebras, Graphcore, Groq and SambaNova have also joined the race, aiming to break into the market that Nvidia has dominated.

Chips are set to play such a key role in AI that they could change the balance of power among tech companies and even nations. The Biden administration, for one, has recently weighed restrictions on the sale of AI chips to China, with some American officials saying China’s AI abilities could pose a national security threat to the United States by enhancing Beijing’s military and security apparatus.

AI supercomputers have been built before, including by Nvidia. But it’s rare for startups to create them.

Cerebras, which is based in Sunnyvale, California, was founded in 2016 by Feldman and four other engineers, with the goal of building hardware that speeds up AI development. Over the years, the company has raised $740 million, including from Sam Altman, who leads the AI lab OpenAI, and venture capital firms such as Benchmark. Cerebras is valued at $4.1 billion.

Because the chips that are typically used to power AI are small – often the size of a postage stamp – it takes hundreds or even thousands of them to process a complicated AI model. In 2019, Cerebras took the wraps off what it claimed was the largest computer chip ever built, and Feldman has said its chips can train AI systems between 100 and 1,000 times as fast as existing hardware.

G42, the Abu Dhabi company, started working with Cerebras in 2021. It used a Cerebras system in April to train an Arabic version of ChatGPT.

In May, G42 asked Cerebras to build a network of supercomputers in different parts of the world. Talal Al Kaissi, CEO of G42 Cloud, a subsidiary of G42, said the cutting-edge technology would allow his company to make chatbots and to use AI to analyze genomic and preventive care data.

But the demand for GPUs was so high that it was hard to obtain enough to build a supercomputer. Cerebras’ technology was both available and cost-effective, Al Kaissi said. So Cerebras used its chips to build the supercomputer for G42 in just 10 days, Feldman said.

“The time scale was reduced tremendously,” Al Kaissi said.

Over the next year, Cerebras said, it plans to build two more supercomputers for G42 – one in Texas and one in North Carolina – and, after that, six more distributed across the world. It is calling this network Condor Galaxy.

Startups are nonetheless likely to find it difficult to compete against Nvidia, said Chris Manning, a computer scientist at Stanford whose research focuses on AI. That’s because people who build AI models are accustomed to using software that works on Nvidia’s AI chips, he said.

Other startups have also tried entering the AI chips market, yet many have “effectively failed,” Manning said.

But Feldman said he was hopeful. Many AI businesses do not want to be locked in only with Nvidia, he said, and there is global demand for other powerful chips like those from Cerebras.

“We hope this moves AI forward,” he said.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.