For House Speaker Mike Johnson, a pressing task: Keep the government open

House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) speaks to reporters after a meeting with Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese on Capitol Hill on Thursday. (Jabin Botsford/The Washington Post)

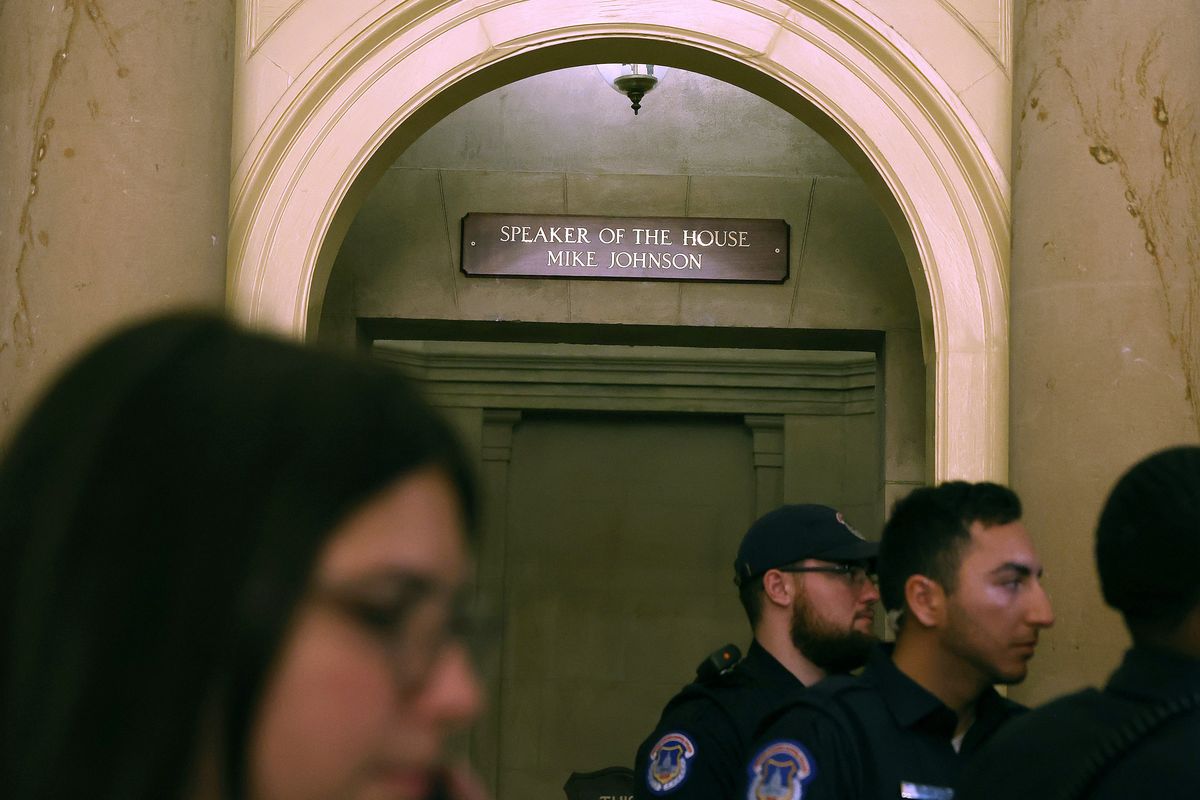

New House speaker Mike Johnson (R-La.) faces immediate challenges to keep the government open, shuttle U.S. aid to Ukraine and Israel and approve funding for federal agencies, a pivotal test for a relatively inexperienced speaker who has focused more on social issues than on economic policy during most of his career on Capitol Hill.

A government shutdown looms Nov. 18 if Congress does not pass a short-term funding measure – enacting individual appropriations bills would probably take far too long, as the House and Senate don’t agree on how much to spend this fiscal year.

President Biden has also asked Congress for $106 billion in supplemental foreign aid and defense funding – including $61.4 billion for Ukraine and $14.3 billion for Israel – and another $56 billion for domestic causes, including child care and broadband internet access. On Thursday night, Johnson indicated he’d prefer to split the Israel funding from the Ukraine aid.

What’s in Biden’s $106 billion funding request for Israel, Ukraine

Johnson must lead the volatile Republican conference through those fiscal fights, the same battles that led hard-liners to oust his predecessor, Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.), who focused much of his speakership on federal spending and had reached, then discarded, an agreement with the White House on overall spending levels for the year.

Up to now, Johnson, who first took office in 2017, has spent more time on antiabortion policy, restricting LGBTQ+ rights and the House’s impeachment inquiry into Biden.

“If you’re picking the top three issues he’s talking about, fiscal policy is not one of the ones he’s picked,” said Maya MacGuineas, president of the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

“It is a trial by fire. He’s a relatively new member of Congress. He doesn’t have an enormous track record,” said Alex Nowrasteh, vice president of economic and social policy studies at the conservative Cato Institute. “He’s going to face immediate challenges that are going to show quite quickly whether he can be an effective speaker.”

Colleagues say that Johnson gained a reputation as a fiscal wonk during his tenure as chair of the Republican Study Committee, a conservative policy caucus, from 2019 to 2021. There he backed policies to raise the eligibility ages for Social Security and Medicare, increase Medicare premiums and extend Trump-era tax cuts for corporations and wealthy earners.

In his first remarks after being elected speaker Wednesday, he previewed his economic policy stances, declaring that the House would vote to create a bipartisan commission to study the national debt and social safety net spending.

“The greatest threat to our national security is our nation’s debt,” Johnson said. “We know this is not going to be an easy task, and tough decisions will have to be made. But the consequences if we don’t act now are unbearable. We have a duty to the American people to explain this to them so they understand it well. And we’re going to establish a bipartisan debt commission to begin working on this crisis immediately.”

Previous Congresses have used debt commissions to try to restructure entitlement programs without saddling either party with responsibility for the changes. Obligations for Social Security and Medicare are the largest drivers of U.S. debt, but have been left out of most recent conversations on deficit reduction.

Biden jockeyed with congressional Republicans during his State of the Union address over conservative calls to cut the programs.

“Rather than focusing on the discretionary portion of the budget, a fiscal commission would look at mandatory spending and revenue. That’s a sensible and reasonable approach to solving these issues,” MacGuineas said of Johnson.

Those goals, though, run counter to one another, some experts say. Extending the Trump tax cuts would add $3.5 trillion to the deficit by 2033, according to a May report from the Congressional Budget Office, Congress’s nonpartisan bookkeeper.

“I don’t think anybody can be taken really seriously if they say that they want to extend those tax cuts, add more on top of them, and also somehow say that they care about the deficit,” said Samantha Sanders, director of government affairs and advocacy at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute.

In the meantime, Johnson faces more immediate economic concerns. Most pressing is the prospect of a government shutdown in a matter of weeks, which would see members of the military potentially miss paychecks, national parks close and the Internal Revenue Service forced to run shoestring operations.

To avoid that crisis, Johnson will have to face some of the same internal GOP disagreements that doomed McCarthy. Last month, with a day to spare before the government would have closed, McCarthy relied on Democratic votes as well as Republicans to pass a stopgap funding bill, called a continuing resolution, or CR.

That triggered a band of eight conservative rebels, led by Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-Fla.), to oust him from the speakership with complaints about McCarthy’s conservative fiscal chops and his willingness to pass legislation that wasn’t on party-line votes. Some Republican fiscal hawks say they oppose CRs on principle and want the government funded only through individual full-year spending bills.

Johnson on Wednesday told Republican colleagues he may take the same tack as McCarthy did, putting a CR on the floor next month to avoid a shutdown and keep the government operating until either January or April, and relying on hard-liners to give him a grace period as a new speaker to cut some unpopular deals.

“He doesn’t get carte blanche,” Rep. Doug LaMalfa (R-Calif.), a staunch McCarthy ally, told the Washington Post on Wednesday. “He’ll have a little more leeway. But if he’s out there going too far on certain things, I think that leeway runs out pretty fast.”

Just before or after the funding deadline, the Senate is expected to send the House legislation with Biden’s emergency request for foreign aid and defense spending. Sens. Patty Murray (D-Wash.) and Susan Collins (R-Maine), the top two members of the Senate Appropriations Committee, are drafting a package for that legislation, and aid for both Ukraine and Israel has wide bipartisan support in the upper chamber.

But Johnson is a skeptic of the effort to fund Ukraine and voted against bills to provide $40.1 billion for Ukraine’s defense against Russia’s invasion in 2022 and another $300 million in 2023. Support for Ukraine has faded within the House GOP’s ranks.

Johnson on Thursday night said he told the Biden administration that House Republicans preferred to “bifurcate” funding for Israel and Ukraine, rather than consider both in a single piece of legislation, posing a possible hurdle for the Ukraine aid.

“The American people are demanding some real accountability for the use of those dollars,” he told Fox’s Sean Hannity. “We can’t allow Vladimir Putin to prevail in Ukraine, because I don’t believe it would stop there, and it would probably encourage and empower China to perhaps make a move on Taiwan. We have these concerns.

“We’re not going to abandon them, but we have a responsibility, a stewardship responsibility, over the precious treasure of the American people. And we have to make sure that the White House is providing the people with some accountability for the dollars.”

Rep. Glenn Grothman (R-Wis.), who has voted repeatedly for Ukraine aid, told the Post that he would not vote to approve the next package, citing a perceived lack of clarity as to the Biden administration’s plan to end the fighting. That dents the pressure from within the GOP that the White House and Senate hope to use to compel Johnson to put Ukraine funding up for a vote, where it would be expected to pass with Democratic votes.

“If Ukraine runs out of munitions and Russia wins that war, that would be a bad thing. I think that fear may cause Mike to reconsider his position,” Grothman said.

“To a certain extent when I voted for it in the past, even I didn’t like it,” he added. “My attitude was … I didn’t want to vote yes, but it puts the Biden administration in a stronger position if a bunch of Republicans say we’re united.”

House Republicans on Wednesday stood up and gave Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries (D-N.Y.) a standing ovation when he said that the House must immediately send aid to Israel. Fewer Republicans stood up, but still a notable amount did, when Jeffries said the House should also send Ukraine more help “until victory is won.”

Another deadline looms soon after next month’s. If Congress doesn’t enact appropriations bills, longer-term legislation to fund individual agencies and programs, by Jan. 1, budget cuts to nondefense programs – including certain antipoverty food assistance programs and medical research – will kick in at the end of April.

Those cuts were part of the deal McCarthy struck with Biden during negotiations this spring over the U.S. debt ceiling, which also set a spending cap for the current fiscal year, but House Republicans now want to spend well below that limit.

That’s where Republican lawmakers said they had the most faith in Johnson. He gained popularity among the conference during his candidacy for his ability to bring the fractious group together and unite the party’s Trump wing with Republicans hailing from districts Biden carried in the 2020 election.

Even if the House blows through the Jan. 1 deadline on appropriations bills, it would probably add language to spending legislation to supersede the budget caps, giving the lower chamber more leverage to negotiate a final deal with the Democratic-controlled Senate.

“I hope that we can ultimately get together and negotiate appropriations bills, and I think we could even do some pre-negotiating,” said Rep. Garret Graves (R- La.), another key McCarthy ally, “meaning even on some of these bills we haven’t even moved out of the House yet, and start trying to negotiate with the Senate and ultimately try get to a good landing place.”