‘A mother of all mothers’: Retired nurse-midwife with new book gets credit for pioneering dual role at Deaconess

Retired nurse-midwife Catherine Shields introduced the midwifery model of care at Deaconess Hospital in 1995. (Kathy Plonka/THE SPOKESMAN-REVIEW)

When Catherine Shields delivered her first daughter in 1972, it was a “nightmare birth.”

Shields said she was forced to lay in a bed in a chilly room with an IV, oxygen and antiseptic smells. Her doctor, a stranger who was curt and distant, “cut a deep incision in my perineum” to place forceps alongside baby Casey’s head.

Later, she felt traumatized if she saw a pregnant woman.

“I’d just about melted down,” Shields said. “I was worried about them, about who is going to be with them, who is going to take care of them?”

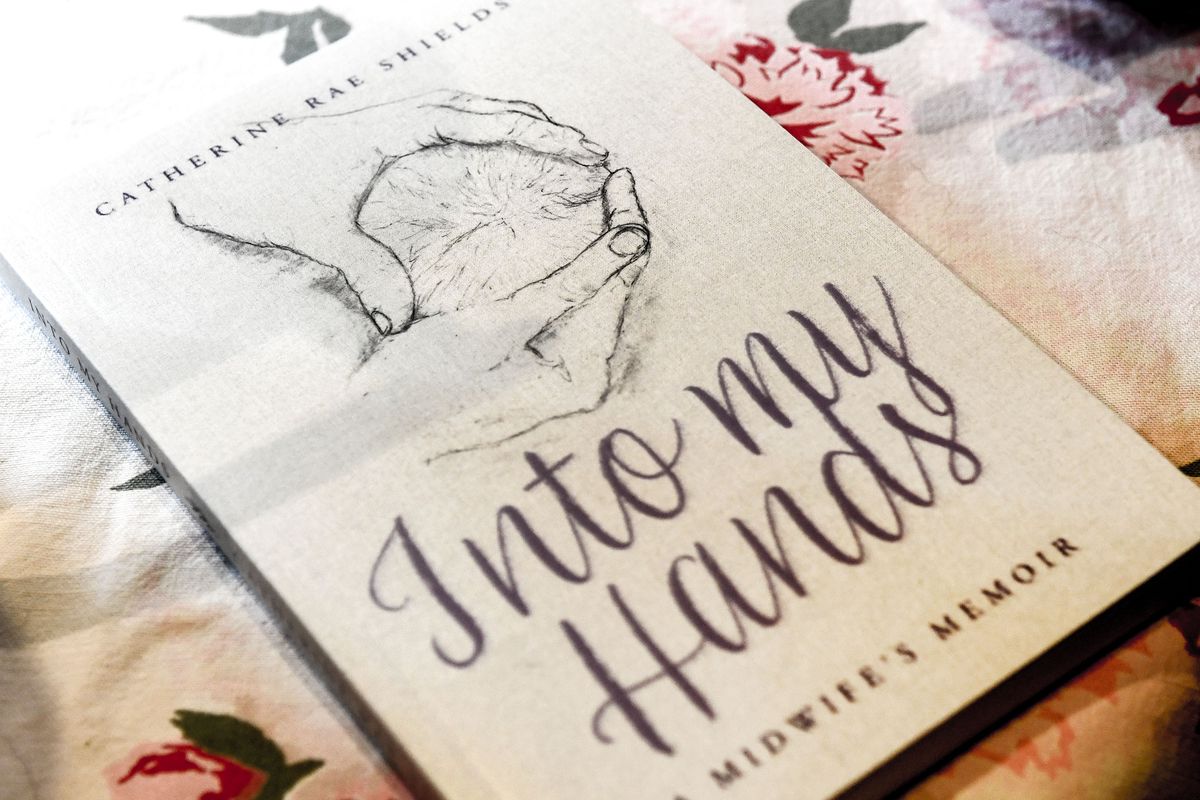

The traumatic birth she described in her new book, “Into My Hands,” is what launched Shields’ eventual career that delivered a new nurse-midwife model of care for women in the labor and delivery unit at MultiCare Deaconess Hospital.

“I decided the only thing to do was to do something about it, so I became a nurse,” Shields said in an interview. “I ended up loving my work.”

Shields’ former colleagues say she pioneered that role by example – with her constant presence, calm voice and soothing techniques. First a Deaconess nurse, she did advanced training to become a nurse-midwife by 1994.

In 1995, she also became director of the Deaconess Women’s Clinic, now called MultiCare Rockwood OB-GYN & Midwifery Clinic. Retired since 2010, Shields describes much of that journey in “Into My Hands,” published in late December.

Her influence continues. In 2023, nurse-midwives handled 38% of births at Deaconess, said Jackie Bartosh, the hospital’s labor and delivery nurse manager. When Bartosh began as a labor nurse, Shields had set that tone.

“Catherine around here at Deaconess is quite a celebrity,” Bartosh said.

“I started working here at Deaconess in 2000, so she was a practicing certified nurse-midwife. The culture at Deaconess was very midwife friendly, and it was very clear to me from the beginning that Catherine was the founder of that culture and mentality.

Bartosh said Shields is “the person who grew all of us young labor nurses up.”

“She taught us what it was like to be with the women in labor and to support them and their families, what it was like to bring a calm presence into their space during a time, really the only time, they’ll experience that birth.”

At Deaconess Women’s Clinic for 15 years, Shields hired its other nurse-midwives while she also worked in that role. Shields said she ensured that all the midwives held the same mindset, to care for a woman throughout pregnancy, and then nonstop during labor and delivery.

“When we went to the hospital, we went when the patient walked in the door, and we stayed,” said Shields, 72, now living in Careywood, Idaho.

Shields knows the exact number of babies in Spokane she delivered as a nurse-midwife: 1,258. She has kept her midwife books where she logged details for each one. But she doesn’t refer to those births as delivering babies.

“We believe, or at least my mentor told me this, that nurse-midwives do not deliver the baby,” Shields said. “The mother delivers the baby. We’re just there to catch the baby, so the mother gets the credit – not us, not the doctor. Who else is doing the work?”

During her tenure, the midwifery clinic was located at the West Central Community Center. It later moved to its present site at 910 W. Fifth Ave.

The nurse-midwives also have provided OB-GYN care, covering women’s health from adolescence to after menopause, and postpartum care. The group would confer with consulting physicians, Shields said, to check records or to step in if surgery or a medical problem required it.

“Midwives have a unique way of caring for people. They don’t forget that. I’m going to add compassionate care. We evaluated them and we stayed with them until the baby was in their arms. I couldn’t see it any other way,” Shields said.

But in most cases at Deaconess, Shields said the midwives do the full spectrum of labor care – monitoring the baby before delivery, coaching the mom, encouraging movement and delivering the newborn.

At Providence Sacred Heart Hospital, if midwives are a patient’s primary care provider, “teams at the Birth Place collaborate closely with them,” a Providence email said. The percentage of births at Sacred Heart involving a midwife wasn’t immediately available.

Shields’ second daughter, Courtney, was born without incident in 1975. But for daughter Annie Rose, in 1980, and son Jake in 1985, Shields had midwives. She found it to be an entirely different, comforting experience, she said.

“What I saw in that was the deep connection, the care and their presence; they didn’t leave me alone,” Shields said. “I wanted women to have that experience of gentle, compassionate care and a listening ear.”

Shields said she introduced birth plans for the hospital. Women could list a wish to be drug-free, to have an epidural, options to move or use a bath. She said midwives encouraged bringing in exercise balls for women to sit on and to have bathtubs installed in rooms.

“The birth plans were kind of laughed at for us at first, but that was mandatory for our clients,” Shields said. “We had them tell us how they wanted their birth to go ideally – out of bed, in the tub, to lean on the bed if your back is aching, to be able to squat.”

The midwifery clinic today has nine nurse-midwives, said Bartosh, who had the group do care for the births of her three children. Shields “caught” two of them. A majority of Deaconess labor nurses have chosen the clinic midwives when having their own babies, Bartosh added.

“I think that says a lot, because we see everybody deliver.”

Bartosh also credits Shields for how she could calm an otherwise chaotic room.

“She has this aura about her that makes you feel calm,” she said. “We all just started to emulate her behaviors and her mannerisms – the things that she’d say that we noticed would calm a patient. We learned her special touches, or the way Catherine would engage with the patient’s significant other or support person.

“She’s a mother of all the mothers. She’s a beautiful soul, and she has helped to bring many lives into this world.”

Shields, who moved to Idaho in 2014 from Spokane, lives with husband Edgar Snoddy. Their home’s multiple photos frame children’s faces, including Shields’ nine grandchildren – five she caught – and one great-grandchild.

She’s kept up with many families who had her as a midwife.

“I pray there will be a midwife for every woman, and whether she is pregnant or in menopause, we can take care of her,” Shields said. “We know the women and their family well. We can take care of them forever.”