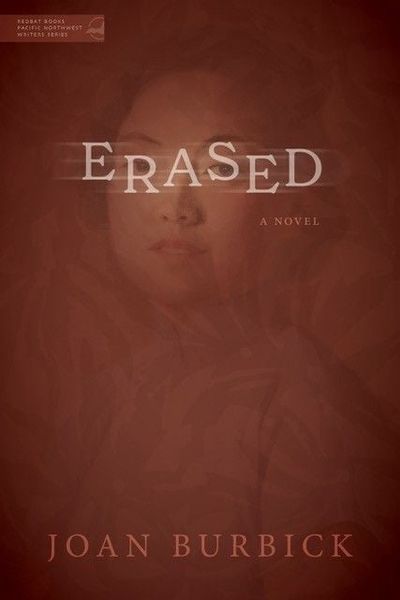

‘Erased’: A writer’s quest to find answers about her husband’s family

The impetus for Spokane author Joan Burbick to write “Erased” happened the way it would in a book: Her husband received an oil painting of his mother, who disappeared in Japanese-occupied China during his early childhood.

“When she looked at that painting, that portrait, she felt some connection to her,” said Alexander Kuo, who is Burbick’s husband and also a writer. “Part of the project was to discover the nature of this connection.”

On Thursday, Burbick, a retired Washington State University English professor, will celebrate her book release, a fictional memoir about Katherine Lin, the mother-in-law she never met but pursued doggedly in research.

“That’s one of my fortes is finding out about things, going through archives and digging,” Burbrick said. “I finally just got to the point like, ‘This is ridiculous. We have to know who she was.’

“We have to understand that she was erased from this family, so it was to defy that.”

Though Burbick has published another novel, “Stripland,” the lion’s share of her books have been nonfiction: “Gun Show Nation,” “Rodeo Queens and the American Dream,” “Healing the Republic,” “Thoreau’s Alternative History” and more.

Before the painting appeared, Kuo’s knowledge was limited.

“The only information I had about my mother was my birth certificate, period,” Kuo said. “And I’m not kidding you. That’s it.

“Her name and her race, which was indicated as ‘yellow.’ This was in Boston, Massachusetts, 1939.”

Both of Kuo’s parents were from China. During a three-year research trip in the U.S., Kuo was born. The family returned to China in 1939, moving to Chungking. Kuo’s mother died when he was young, and when the war ended, his family moved to Hong Kong, where he lived until he attended college in the U.S.

Though the book is published as fiction, many of the characters have real-life counterpoints, including the character of Kuo’s mother.

“Almost all of the characters in this story that are based on real characters have died,” Burbick said. “So there’s a parallel narrative where I assume his mother’s voice, because I found out certain things about what she did.

“I tried to find out everything I could about that period of time – I just did a deep dive, literature, history, movies, anything that brought back the moment. And we did know at one point that she traveled across the country, with my husband, through occupied territory, to China to get to the West from Shanghai, so that was almost 1,000 miles.”

Part of what made Burbick more comfortable taking on this topic is that she and Kuo have regularly visited China to teach and lecture over the past 20 years.

They had visited many of the places his mother would have been during her journey, and she was able to research using primary documents, such as letters Kuo’s father had sent. Unveiling information about his mother revealed hard truths.

“It was a dangerous place for him, because these things are hard to find out, and you have to be strong,” Burbick said. “He’s one of the strongest people I know. He was a child during war. He lost his mother during war.”

Kuo acknowledges that there can be hurdles in the subjects Burbick tackles in her book.

“From the objective point of view, I think that kind of book, research work, written by a white woman in that area that is, at best, at the very beginning, very foreign to her – and that is not meant as an insult,” Kuo said. “But through a series of going to China, different cities, and Hong Kong for the last 20 years, that made a huge difference, which shows me that my wife welcomed new opportunities of learning and living.”

Kuo sees Burbick’s book as a gift to him, and something only she could have written.

Burbick said she learned about the nature of secret-keeping from this project.

“It creates violence,” she said. “And it goes on generationally.”