Review: “Tom Foley: The Man in the Middle” tells life of Democratic politician elected to a heavily Republican district

As the U.S. Congress reached a historic low of public approval this year, and amid polarizing partisan politics, few Americans might have realized the path to the bottom began in Spokane.

The first step in the continental divide that would separate two-party American politics began when voters ousted a former Spokane prosecutor from a three-decade seat in Congress in 1994.

Tom Foley may well have been the last Speaker of the House presiding over a Congress where coalitions were built and bridges extended across party divides.

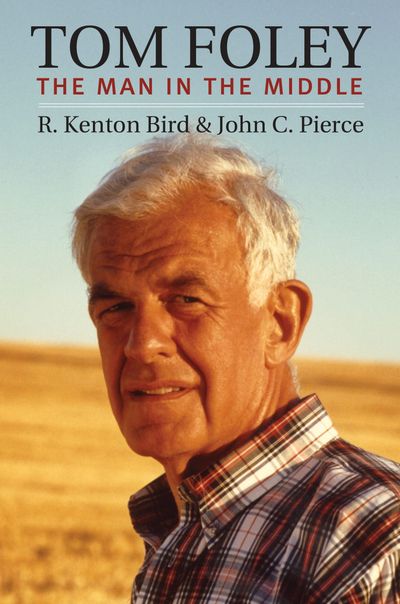

That story of a centrist who could get jobs done in Washington, a Democrat elected to a heavily Republican district where constituents benefited from his work, gets a detailed telling in “Tom Foley: The Man in the Middle” by R. Kenton Bird and John C. Pierce.

The two academic professors, Bird in journalism and Pierce in public affairs and liberal arts, tell a fascinating tale of Foley’s political career in the context of the increasing polarization of American politics.

The Democrat took office in 1964 in a Republican bastion of a district, riding what would today be called a blue wave behind President Lyndon B. Johnson. He would stay in office until 1994, rising to Speaker of the House for six years, before falling amid a Republican political backlash led by Newt Gingrich, which would lead to the divisive and deadlocked federal government we’re experiencing today.

Bird and Rich manage to traverse the edge of a slippery political climate to tell the story of Foley’s life squarely in the center. He was able to cross party lines and draw votes, first as an agricultural chair, and later as majority whip to Tip O’Neill and then as Speaker, second in line of ascension to the President.

The authors take such care in remaining as neutral as their subject; the book weighs more academic than literary. This is not the kind of narrative that will inspire an epic Broadway musical. Although make no mistake: Foley was usually in the room where it happened.

Political junkies and political science both will lose themselves in this deep dive into how Congress lost its way and how America became so divided, both politically and culturally.

When Foley was rising to power, public confidence in Congress were consistently high. With few exceptions, that slide began after he left office and continues today.

Meanwhile, Foley became a hero for Washington farmers by helping broker the dam and irrigation projects on the Columbia and Snake rivers. He pushed back against his own party to support President Clinton’s efforts to pass the North American Free Trade Agreement with bipartisan support, which boosted agricultural exports back home.

When Foley was in office, and through his leadership, voters saw government as a tool to get this done. Congressional colleagues, meanwhile, saw Foley as a politician who always looked to do the right thing, even when it meant bucking his own party.

But a drawing of the 5th District map in 1972 began to gradually stack voters who began to listen more to Missouri radio talk host Rush Limbaugh’s increasing dim view of America. Fueled in the 1990s by Gingrich’s “Contract for America,” the idea became not to get things done but to grab and hold onto power.

Stalemates and political rancor became the order of the day.

This is not only a story of Foley and his fight to hold the middle, it’s also the story of how American politics became broken to the point that it lost public confidence.

But none of that was Foley’s fault. Yes, he may have underestimated the influence that ultra-conservative politics and media would wield. He may have worked so hard at holding Congress together as Speaker that he neglected campaigning at home (he lost by a mere 4,000 votes). Foley became a casualty in the war for absolute power.

Foley was a man in the middle who got caught in the center of one of the most heated cultural and political wars of recent times. The Spokane Democrat may have been the first Speaker voted out of office by his home district since Abraham Lincoln’s administration, but it didn’t defeat his memory.

The most telling testament to that bipartisanship came when the man that took back the 5th District seat for Republicans, George Nethercutt, led efforts to name the U.S. Courthouse in Spokane after Foley.