James Patrick Thomas returns to Eastern Washington to discuss debut book detailing more than a few pilgrimages for peace

James Patrick Thomas’ voicemail ends with “I wish you peace.”

It’s the kind of sentiment you’d expect to hear when reaching out to a man whose life has been, in many ways, a decades long pilgrimage for peace. There’s the physical 6,700-mile-long pilgrimage he took by foot through nine countries in an attempt to end the nuclear arms race, and the figurative quest to discover the impacts of the nuclear contamination poisoning Eastern Washington. There’s also the journey he’s undertaken within his faith, and himself, as a Jesuit.

In his debut book “Atomic Pilgrim,” a memoir of Thomas’ many pilgrimages, he details his experience and lessons learned on those different journeys, while exploring their many intersections and ties to his own upbringing in the Inland Northwest. Local readers will have the opportunity to hear Thomas discuss “Atomic Pilgrim” at 7 p.m. Tuesday at the Myrtle Woldson Performing Arts Centre at Gonzaga University as part of The Spokesman-Review’s Northwest Passages series.

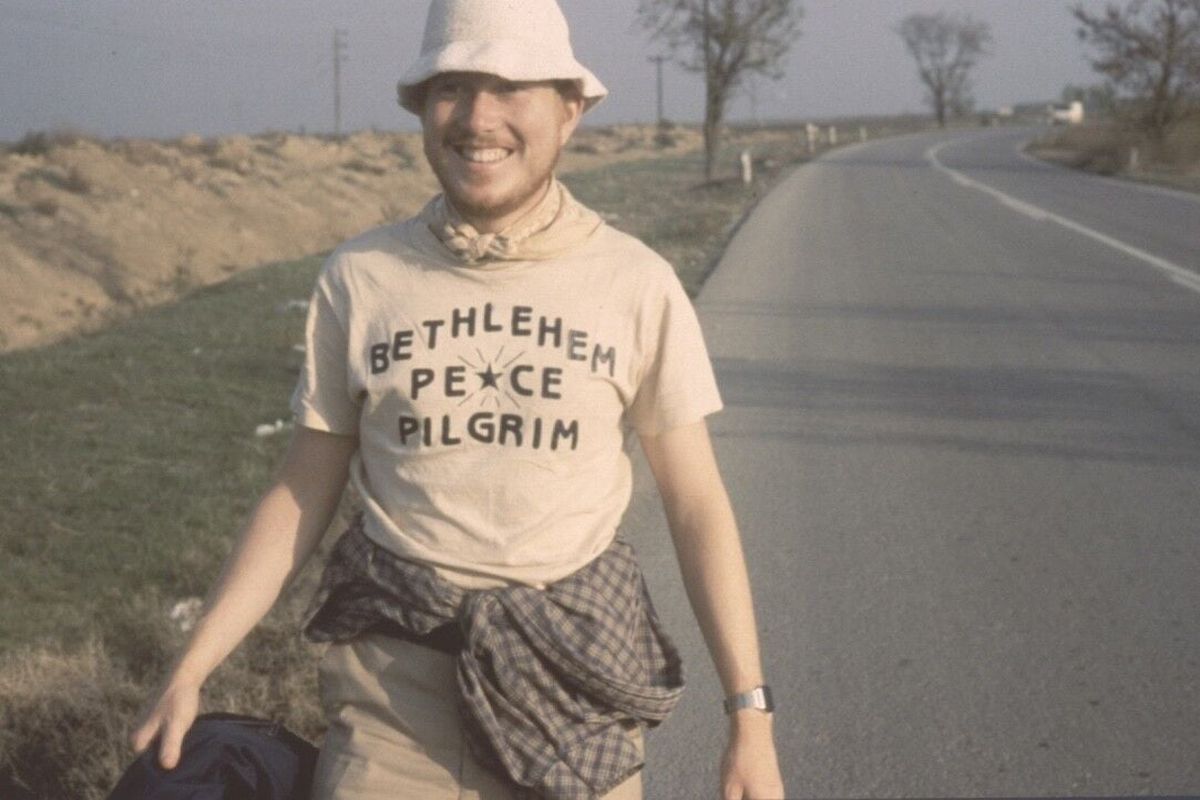

Starting with his upbringing in Great Falls, Montana, Chewelah and Spokane, under the specter of the Cold War, Thomas invites readers to walk step for step with him as a member of the early 1980s Bethlehem Peace Pilgrimage for nuclear disarmament, and then backtracks to the region he grew up in by sifting through thousands of government records to understand the impacts of the nuclear weapons production conducted at the Hanford Site starting in the 1940s. All the while, he explores his own faith.

“I wanted to have a life that was more like the one in the Gospel, of the early disciples following Jesus, and that’s what the pilgrimage was like for me,” Thomas said. “It was scary for me to think of living as a vagabond for the better part of two years, not knowing where my next meal was, certainly not knowing when the next shower would be, not knowing exactly where l’d be sleeping each night. But it was also at a time when the peril of nuclear war was very, very real.”

In an interview last week, Thomas said he looks forward to returning to Spokane. Now based in Seattle, his journey detailed in “Atomic Pilgrim” begins in the Lilac City just after he graduated from Gonzaga with theater and broadcast degrees and became an operations engineer for KREM. While he has nothing against his former employer, Thomas said he did not find the job fulfilling after a few years and began looking for a calling with more meaning.

That higher calling came in 1981, and from an unlikely but fitting source: Mother Theresa. Thomas said he was watching a documentary on her life on the local public television station one night, and at one point in the program, the documentary reporter asks her “How do you know you’re doing God’s work?”

“And her response was very simple; it was ‘Love until it hurts,’ ” Thomas recalled. “And I got a feeling in my gut that my life had just changed, and it was the next day that I sent off a letter asking for an application to the Jesuit Volunteer Corps.”

Within months, Thomas was in Seattle at the front lines of the growing push against the nuclear arms race, inspired by local leaders like Father George Zabelka, the former U.S. Army chaplain who blessed the bombers who dropped the nuclear warheads on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and went on to spend years advocating for disarmament. He later lamented his participation after seeing the devastation in Japan with his own eyes. The suffering those who lived through the blast and the fallout left a lasting impression on Zabelka and in recountings of the experience, Thomas as well.

“He saw a number of people die literally before his eyes; that always sticks with you,” Thomas said. ” … When you hear somebody talk about that, their eyewitness account of it, it gives you a deeper sense of the profound risk we take each day when we have thousands of nuclear weapons between Russia and the United States, a number of them on hair-trigger alert.”

“The stakes are really, really serious, and we have to have the concerted will to make steps toward peace and disarmament,” Thomas said.

Zabelka, at 67, was the oldest member of the pilgrimage, and had joined a number of faith leaders in the Northwest confronting what Thomas describes as the figurative tip of the American nuclear spear, the many submarines stationed at the Bangor naval base on the Kitsap Peninsula each capable of carrying the equivalent of 5,000 Hiroshima bombs. Protests plagued the site throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, and it’s in that backdrop that the 19 members of the pilgrimage crafted their plans and set off on their journey.

Their journey was long and arduous, spanning the U.S, Europe and the Middle East. Various groups joined Thomas, Zabelka and the rest of the pilgrims for varying durations and distances as word spread. It would be 20 months before Thomas was back on American soil, and he credits his faith for carrying him through.

“It goes back to what I was saying earlier about that saying from Mother Teresa: ‘Love until it hurts,’ ” Thomas said. “That we have to be willing to sacrifice our comfort for the good of others and the good of the future of the world.”

Thomas embarked on his next journey within a few weeks of his return, this time assisted by a local group that would come to be known as the Hanford Education Action League. Although plutonium development had been occurring at Hanford for decades, Thomas explained the public had little insight into the operations and its impacts.

“About the only thing we knew and could find out was that Hanford plutonium was in the bomb that was dropped on Nagasaki,” Thomas said. “But as far as what had happened for 40-plus years at Hanford, since World War II, it was literally a black hole. There was no information available.”

Through thousands of records released in Freedom of Information Act requests, HEAL, Thomas and local journalists uncovered the devastating health complications those living in Hanford’s shadow were contending with as a result of radiation exposure. Their efforts led to the release of several documented instances of the intentional release of radioactive materials into the region while Hanford was active, including the Green Run. The large scale 1949 operation spread radioactive iodine-131 as far north as Kettle Falls and as far south as Klamath Falls, Oregon, according to the U.S. National Park Service.

“We were thinking we’d find something akin to the Three Mile Island accident, but what we found was much, much more serious,” Thomas said. “Almost all of the radiation Hanford released over those 40 years was because of routine operations.”

There were no equipment failures, he said.

“Everything was working in the plants as designed,” Thomas said, “but because of the secrecy, they were able to operate very cavalierly and basically hid behind an iron curtain of secrecy until 1986.”

Thomas still carries the stories, grief and frustration of those in the affected areas, known as downwinders. He witnessed their fight to be heard, their health deteriorate over the years and in recent years, their deaths.

“They did not have to suffer as much as they did,” Thomas said. “If the government would have come out in the ‘70s when it shut down the plutonium operations the first time and notified people.”

The process of putting together the book took months of poring over accounts from his fellow pilgrims, Thomas’ own records and thousands of government records, but Thomas believes the memoir is as timely as ever. The scope of nuclear war and international conflict has reared its head again, and the additional nuclear capacity between several global powers only adds to the potential for disaster.

“It’s only a matter of time before there is some misstep or false alert that doesn’t get recognized as a false alert – we’ve had dozens and dozens of those, just between Russia and the United States over the last 80 years,” Thomas said. “And if you increase the number of weapons and the different countries, you’re just working the wrong way at the odds of maintaining a peaceful world, or at least as peaceful as it is now.”

Thomas still has faith though, particularly in the power of the individual banding together with others to make an impact. That was his experience on the pilgrimage and in his work with the Hanford Education Action League. He hopes “Atomic Pilgrim” serves as an inspiration for others to effect change.

“That’s what I’ve experienced both with the Peace pilgrimage as well as with the Hanford Education Action League there in Spokane,” Thomas said. “We were just ordinary citizens in both instances, and we took on these very intimidating national security issues and said, ‘We are citizens of a democracy, we have a right to this information and we have a role to play in the decisions being made, both with regard to our nuclear posture as a country, but also needing to protect our local health and environment.’

“We basically fought our way in, and we changed the course of history, especially at Hanford.”