Summer Stories 2025: ‘Ill Wind’

We didn’t eat the baby

Till we burned up all the wood

Considering that she was raw

She tasted pretty good

– From the folksong “Tasty May,” American trad.

Now that we were free of vaccines, we could finally pursue the illnesses we’d always longed for, from dengue fever to typhoid fever to yellow fever to Saturday night fever and all the fevers in between, not to mention smallpox, which we were all hoping to get, and measles, which some of us were currently enjoying, or rubella, which none of us even believed existed. Then there was mumps, which was fun to say and fun to get because of how it made our faces swell, and of course, polio, which had always seemed so out of reach, so old-fashioned and presidential, but was now available to everyone, not just the top-hat-wearing elite.

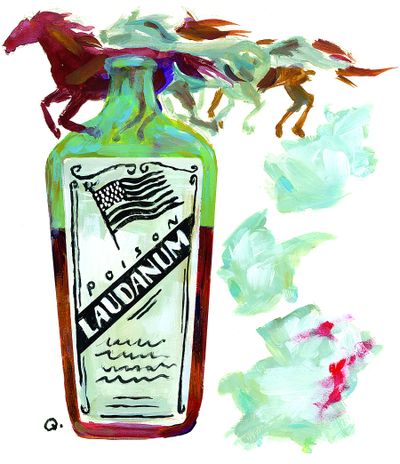

Mother most wanted diphtheria because 1) the smell that accompanies it is like rotting grapes, and 2) the old fashioned name for it is Putrid Throat, which is almost as enchanting a name as Galloping Consumption, which Grandma most wanted because it reminded her of stampeding horses and also of the olden days, when sanatoriums dotted the landscape and so many famous people were coughing themselves to death, like Edgar Allen Poe and Emily Bronte and Anton Chekhov and Jimmy Carter and Andrew Jackson, not to mention all the other founding fathers and mothers and sisters and cousins. Was there ever anything more American or European or African or Asian than dying from some painful, stinky, withering, rotting, debilitating disease? I most wanted chickenpox, which felt like a good starter sickness for smallpox, my most cherished disease because of the way if makes your skin bubble, leaving open sores, and how you might hallucinate throughout the high fevers, and how only the worthy will survive infection and become eligible for further illness. All the poxes were excellent, but monkeypox and cowpox were special favorites in our family because of their animal names. Dad wondered if we could maybe crossbreed the poxes or develop new poxes of our own to share with the world, like Sasquatch pox or slug pox or marmot pox.

Mother took laudanum every day, nodding off on the fainting couch around midmorning, then waking and taking more laudanum. She always wanted more laudanum and also more babies, lots more babies, hers or anyone else’s, and she wanted to brine the babies and roast them and eat them, which, so far we had only managed once, on the Fourth of July, though Mother said we should gather enough babies so we could roast one every Sunday, and Father was building a corral big enough to hold thousands. Mother said it wasn’t a sin to roast babies as long as we cooked them thoroughly and didn’t exhaust our supply, leaving some babies to grow up and get jobs to pay for Mother and Father’s social security benefits. And we kids wanted more babies so we could dress them in Disney costumes and teach them how to walk and talk and get sick and refuse vaccines, making dozens or hundreds of baby headstones in the family plot, just like the olden times, when everything was better, but also sometimes worse.

Father often talked about the olden times, how back then the government would try to prohibit us from getting sick, which felt like the most un-American thing we could imagine. We had every right to our illnesses and intended to be sick always and spread our sneezes and juices among our brethren as crop dusters spread fertilizer over fallow fields. We had never cared much for germ theory or the single shooter theory or the theory of relativity or the theory of gravity or any other theories. We came from a long line of healers and holy (wo)men who specialized in making people sick, easing them off this mortal coil and into the arms of various colonial demigod angels taking tickets at the gates of heaven. And because we were self-taught, we were unencumbered by the lies of the effete elite, as Dad called them, who seemed to think they were better than the diseases that surrounded them. We thought otherwise.

We’d been wanting to die in the most horrifying ways from the very beginning.

Banishing fluoride had been a good start. At least we lost our teeth quickly.

But there was so much more we wanted to lose.

Which was why Great Grandfather started a leper colony outside Walla Walla in the late 1940s, only to be shut down by jackbooted thugs from the federal government who said the most horrifying things anyone could imagine: “We’re from the government – and we’re here to help,” insisting upon treating the lepers with drugs, as if the government itself was some kind of god, denying tens of thousands of Americans their right to lose arms.

We prayed for a plague to return – not a middling plague, but an enormous one, a black death that would kill almost everyone, like in the 14th century when half of Europe was wiped out, raising wages for everyone left behind. In modern times, people sometimes talked about diseases as if they were plagues, but they never killed almost everyone, especially when the government tried so hard to keep us alive and kept taxing us and bossing us around.

It became my job to find the babies for Mother to brine, which I tried to do at the bus station and in shacks attached to certain farmers’ fields, and anywhere else babies might be found, such as meatpacking plants and railyards. I was supposed to round them up and bring them home like kittens in a burlap sack.

It was my duty. And my God-given right.

Grandfather always said that true religion was at its peak during the dark ages, which were only troubling times if you were afraid of the dark, which we were not. And are still not. Darkness is the greatest gift promised to all living things, Grandpa said. And yet …

And yet …

The problem was I couldn’t bring myself to fetch the babies home.

I wanted to.

I knew if they were a little older they’d want to be as sick as I wanted to be.

But I didn’t know if they’d want to be eaten.

I knew it was a sin and a curse to leave them with their families.

The problem was seeing their faces. And their fat little hands.

I thought it might be better if we imported them for Amazon to deliver packed in ice, tariffs be damned.

The only baby we had eaten so far was my baby sister Kitty, and she tasted like pork, as Father said she would. It was kind of weird, to tell you the truth – not just eating your sister, but enjoying her so much with Mother’s gravy and dumplings and green Jello.

Kitty had never even enjoyed a major illness, dying as she did in her sleep for no apparent reason. Bad air, Mother said. Vapors. Which may have been a kind of illness, though Kitty didn’t get to suffer much.

The truth is I didn’t really want to abduct anyone.

I wanted them to enjoy their suffering, and while I was happy to share my illnesses and fight to keep the babies vaccine-free, it didn’t seem right to just take them.

Mother said it was either take them and eat them or shoot them in the face and send them to Bolivia. It was the law, she said, and we couldn’t go against the law.

Sometimes I hated the law’s guts.

I knew it was wrong to think that way.

I knew my main job was to get sick and die.

And I wanted to.

I really did.

Like Lynyrd Skynyrd falling out of the sky in flames.

But sometimes I wondered why I had to wait so long.

“All good things come to those who wait,” Mother said, nodding off at the kitchen table as she fed Baby Roy some kind of goopy meat paste.

And then I felt it, a tickle in my spine like a whisper of what was to come, then a dizzying wave of fever, the walls starting to melt, the floor warping, as if I had taken laudanum myself – Smallpox, at last! I knew it! – saving me from days of failed baby-gathering! And maybe, if I was lucky, nearly killing me and everyone else. I fell to my knees prepared to cherish each back-breaking, feverish moment of the disease, and prayed I’d be worthy.