The proudest Yankee

FORT WORTH, Texas — This is still a haunting memory for the man who accompanied Billy Martin’s death ride into an icy ditch on Christmas 1989.

“It’s a real bad time of the year,” said survivor Bill Reedy, now 68, who lives in Milford, Mich.

Martin, known for his four turbulent decades in the majors as a gritty player and a scrappy manager, died the way he often lived: recklessly, ironically, violently and full of booze.

He took four teams — Twins, Tigers, Yankees and A’s — to the playoffs.

He was hired and fired five times by Yankees owner George Steinbrenner.

Martin’s life ended, sadly enough, a fungo swing away from his farm house near Binghamton, N.Y., while in a two-tone, blue-and-white Ford 4X4 pickup traveling “17, 18, 19 mph, no more than that,” said Reedy.

Martin’s mother preceded him in death by just two weeks.

A depressed Martin asked Reedy, who had been his friend for nearly 20 years, to be with him for the holidays. They spent that Christmas afternoon together, just talking and bar-hopping. They drank Russian vodka and beer.

When it was time to pay the last bar bill and rejoin their wives back at the farm, darkness had fallen. It was brutally cold. The roads were snow-crusted and icy.

Martin was intoxicated from several days of heavy drinking, but no one could drink more and show it less than the wiry man with the fiery temper.

Martin, according to Reedy, was behind the wheel … a controversial fact that conflicted with original police statements and was debated in the courts.

Anyway, Martin missed his turn.

He was talking about his late mother when he drove past his normal exit off the highway. But rather than turn back, he kept going and took an alternate route across a series of winding, hilly, unlit roads that approached his farm from the opposite direction.

At 5:45 p.m., Martin turned left onto Potter’s Field Road, then tried to negotiate an immediate right into his driveway.

The truck lost traction. It became a three-quarter-ton refrigerator on skates. Martin blurted out something cautionary to Reedy, then fought the steering wheel.

The truck slid past the Billy Martin monogrammed brick entry … and slammed into a concrete culvert.

Martin died at the scene from a broken neck. He was 61.

Neither passenger was wearing a seat belt.

Recalled Reedy: “I mean, Billy missed the driveway by maybe 18 inches.”

Who was driving?

Martin never liked Christmas.

He was reminded of his childhood in Berkeley, Calif., where there wasn’t enough money for presents after his father walked out on the family.

The connection stayed with him a lifetime.

“Billy was very religious,” Reedy said. “He read the Bible and could argue it with anyone … and could do the same thing on the Civil War. He was knowledgeable about a lot of different things. People don’t know that about him.”

Reedy, a former newspaper printer and restaurateur, now works as a union consultant in Detroit.

After Martin’s death, Reedy stopped drinking. He and his wife, Carol, went nine years without putting up a Christmas tree. It took the birth of their first granddaughter in 1998 to get them to change.

Reedy originally told police that he had been driving the night Martin was killed. He later changed his story when he realized that he no longer had to “cover” for his best friend once he was dead.

“That’s the truth,” Reedy said.

Martin’s only son, Billy Jr., now 40, a sports agent based in Arlington, Texas, has accepted the fact that his father was driving.

“I don’t hold Bill Reedy responsible. I don’t care who was driving,” Billy Martin Jr. said. “It’s not going to bring my father back. Besides, I know Bill would’ve taken a bullet for my father — and vice versa.”

Six years ago, Billy Jr. named his first of three children after his dad’s best friend.

Good and evil

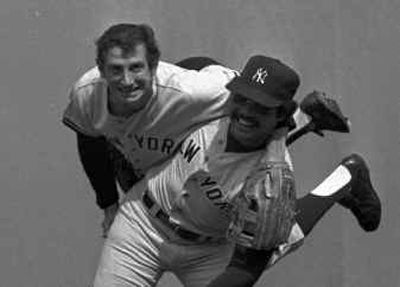

Martin was one of baseball’s most colorful and pugnacious characters.

His love-hate relationship with Steinbrenner became a popular Miller Lite Beer commercial in 1977.

Martin was known for his dirt-kicking tirades with umpires and total fearlessness in barroom encounters with anyone who wished to fight him.

He brawled with his own players. He once even fought with a marshmallow salesman over a few drinks in Minnesota.

The late columnist Jim Murray once wrote: “Some people have a chip on their shoulder. Billy has a whole lumberyard.”

Martin particularly liked Texas, where he took up his first job as a big league manager with the Rangers in 1974. In many ways, he was more Old Wild West than laid-back California.

The Rangers ended up firing Martin, but not until he took over a team that had lost 105 games in `73 and went 84-76 in `74. Martin made the players believe they weren’t the dregs of baseball and that they could finish just five games back of the eventual world champion Oakland A’s in the A.L. West, which they did.

Frank Lucchesi, Martin’s third-base coach and successor with the Rangers, remembers Martin for slipping a 12-year-old kid a $20 bill during a Dallas-to-Oakland flight one Christmas so that the boy could buy his mother a present … and finding the late Merrill Combs a job on Martin’s Rangers staff because Combs needed only 45 days to qualify for his baseball pension.

“People don’t know the big heart that Billy had,” said Lucchesi.

Power and paranoia

Martin kept the same attitude with all his managing stops: “If they want to win, they ‘need’ me.”

He would gladly kick-start any team that accepted his services.

But along with power came paranoia.

Martin was never sure who was with him … or against him. Some say it consumed him.

“Billy was amazingly paranoid,” said former Rangers All-Star catcher Jim Sundberg. “He was very strategic. He knew how to motivate players. But Billy had some very rough edges.”

Sundberg remembers two different Martins with the Rangers: the `74 version who won and the `75 version who was about to be fired.

“Billy was drinking a little heavier by the second year,” Sundberg said. “Sitting next to me in the dugout, he’d start to nod off during games. It became extremely difficult to play for him.”

Martin’s behavior could be erratic.

“If Billy didn’t like the music being played between innings,” Sundberg said, “he’d rip the phone off the dugout wall.”

Another time, Martin slapped Rangers traveling secretary Burt Hawkins during a 1975 team charter because Hawkins’ wife had organized a wives’ luncheon while the players and coaches were on the road.

Buried with The Babe

Lucchesi saw Martin at the baseball winter meetings in Nashville, Tenn., about 10 days before he died.

“Billy told me to get ready,” Lucchesi said. “He was coming back to manage the Yankees again.”

If Martin were still alive today, he would be 76.

“He’d be dressed great,” Reedy said. “Life of the party.”

“My father was one of the most entertaining, fun human beings you ever hoped to be around,” Billy Martin Jr. said. “You don’t always hear how he cared about the little people in life.”

Martin is buried in the Gates of Heaven Cemetery at Valhalla, N.Y.

His grave is about 90 feet from Babe Ruth’s.

Steinbrenner paid for Martin’s burial. Billy’s tombstone reads: “I may not have been the greatest Yankee to put on the uniform, but I was the proudest.”

Martin also holds a place of sanctity inside Monument Park at Yankee Stadium. Despite being a modest .257 career hitter (plus .333 in 28 World Series games), he’s right there in center field with the most fabled Yankees sluggers: Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio and Mickey Mantle.

Martin’s monument reads: “There has never been a greater competitor than Billy.”

Peter Golenbock’s 1994 book “Wild, High and Tight: The Life and Death of Billy Martin” details the controversies, the barroom brawls and the lawsuits. Reedy said it’s probably the most factual book ever written about his friend.

It also puts Martin behind the wheel on Christmas 1989.

“You can’t dwell on the damned thing,” Reedy said of Martin’s death. “But you can’t get it out of your mind, either.

“I just miss him.”

In truth, so does baseball.