How wineries stave off trouble

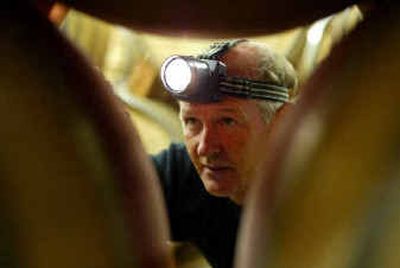

NAPA, Calif. — THWACK, THWACK, THWACK! The sound of master cooper Douglas Rennie hammering metal hoops off a leaky barrel thunders down the long corridors of the Stag’s Leap Winery cave.

It’s noisy work, but quick. In minutes, Rennie has whipped out the offending stave (the skinny pieces of wood that make up a barrel’s sides), replaced it with a new one and — WHAM, BANG, BANG! — put the pieces back together.

Technology may reign elsewhere in the wine business, from computerized inventories to aerial photos of vineyard growth, but it’s all about tradition for barrel repair, a resolutely high-skill, low-tech art.

“I love the job,” says Rennie, a fourth-generation cooper, the traditional term for barrel maker. “I’ve been doing it 30 years; it’s what I know.”

For all their simplicity, barrels are a critical and lucrative part of the premium wine industry. Rennie works for the Napa arm of the well-known French cooperage Seguin Moreau; the U.S. operation, Seguin Moreau Napa Cooperage, sells about 50,000 barrels a year with revenues of $25 million to $35 million.

More than 240,000 French oak barrels were imported to California in 2002, and another 59,000 barrels were imported from Hungary, according to a report by St. Helena-based wine analysts Motto Kryla Fisher.

Barrels are more than just a collection of staves knocked together. Before they’re filled with the grape juice that will become wine, the insides of the barrels are toasted by fire pots placed inside. The toasting caramelizes the wood sugars, which lends flavor to the wine.

Winemakers order the level of toast they want, controlling how the finished product will taste.

“In a traditional winery, part of the signature style of the house can come from the cooperage,” says Bo Barrett, winemaker at Chateau Montelena Winery in Calistoga.

Barrels run in Rennie’s family. His father, grandfather and great-grandfather all made whisky barrels in Scotland and he remembers going to the works with his dad as a boy of 10 and being “just fascinated” by the activity.

Whether he’s fixing one barrel or 20, Rennie works with the same kind of tools his great-grandfather did, like the adze, which smooths rough-cut wood, and the croze, used to gouge the groove into which the barrel lid fits.

“It’s nice to have four generations, but it doesn’t make me any better than any other cooper,” Rennie says. “You have to earn that, earn the respect that you’re willing to sweat.”

And he does.

At Stag’s Leap, Rennie was red-faced with exertion as he worked the new shave in with its brethren, planing the wood smooth and sending curlicues of shorn wood fluttering to the floor.

For the final step, he whirled the barrel with one hand and brought down his hammer with the other, wielding the tool with a percussionist’s precision as he banged the hoops back into place.

BOOM, BOOM, BOOM, he was done.