The unkindest cuts

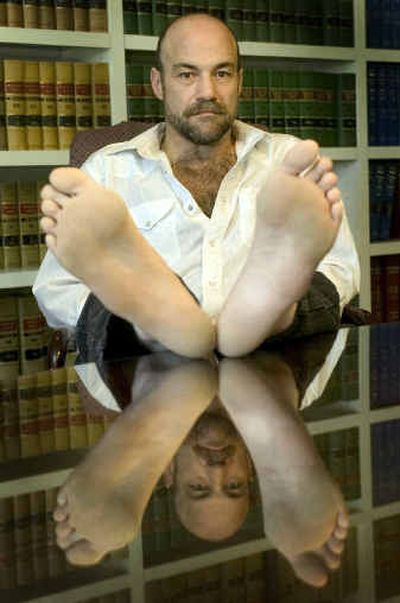

Steve Rudd needed another foot surgery. A Spokane doctor who had operated on Rudd’s foot once before did a second surgery on Sept. 27, 2001.

This time on the wrong foot.

“When I woke up, Dr. Padrta was sitting next to me, holding my hand and crying,” Rudd said.

A nurse at Holy Family Hospital had prepped and draped Rudd’s left foot for surgery instead of his right. The surgeon didn’t notice and fused the bones in four of Rudd’s toes.

On July 1, new national rules went into effect that may prevent so-called “wrong-site surgical errors.” The rules came too late for Rudd, who has filed a malpractice suit against Dr. Brian Padrta and Holy Family.

But already the rules are changing how Inland Northwest surgical teams do their work. Holy Family and other hospitals in the region have changed their practices. Hospitals could lose their accreditation if they don’t follow the new rules.

Two legs, two kidneys, 10 fingers, 33 vertebrae – the human body presents many chances for error. Throw in a flip-flopped X-ray, a typo on the medical chart or a last-minute change of surgeons and you’ve got fertile ground for disaster.

One of the new national rules requires surgeons to mark the correct surgical site with a permanent marker while the patient is awake. Suggested marks are a “yes” or the doctor’s initials. An “X” is too ambiguous because it could mean either “wrong leg” or “X marks the spot.”

Another rule requires the surgical team to pause in a “time out” before surgery begins to verify the patient’s identity, the procedure and the site of surgery.

“It is long overdue and an example of the kind of basic safety procedures we should have had in medicine a generation ago,” said Dr. Robert M. Wachter, co-author of “Internal Bleeding: The Truth Behind America’s Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes” and a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

Which foot?

Rudd, 44, was a construction worker until a fire hydrant assembly fell on his right foot.

It was Nov. 10, 1999. He was on his knees in a ditch, working in Ellensburg on an underground utility system, when the 1,800-pound assembly fell from a mechanical lift.

He spent several days in a hospital in Ellensburg, then returned to his home in Spokane.

Rudd first saw Padrta, an orthopedic surgeon, on Nov. 20, according to Rudd and his attorney, Roger Felice. Padrta operated on Rudd’s foot on Nov. 22, reclosing the swollen wounds.

Two years later, the toes on the injured foot had healed, but were bent and misshapen. Padrta and Rudd decided to attempt another surgery. Padrta thought the foot could be reshaped by fusing the bones in the toes, Rudd said.

At the hospital, Rudd remembers “two or three people” asking him which foot needed surgery. He remembers discussing his surgery with someone at the admitting desk, a nurse and an anesthesiologist. No one marked his foot.

He was given a sedative. The next thing he remembers is waking up with the surgeon at his side in tears.

The mistaken surgery left him with a limp and pain that several physical therapists have tried and failed to resolve, he said. Rudd now is retraining to work in a sedentary job with computers.

“There are a whole bunch of things I don’t do no more,” Rudd said. “I used to train horses, water ski. I can’t run.”

He displayed a dark sense of humor about the event: “I’m just glad I didn’t go in for a vasectomy,” he said.

Cathy Simchuk, a Holy Family vice president, said the hospital “is not disputing an error was made.” For unknown reasons, she said, the patient had a sock on his right foot and a bare left foot. A nurse looked at the bare left foot, observed that the toes appeared bent and in need of surgery, and prepped that foot in error.

The hospital since has added more steps to what was, in 2001, a seven-step procedure for preventing wrong-site surgery, Simchuk said. Today, a surgeon would mark the patient’s foot while the patient was still awake in a holding area outside the operating room. In addition, all members of the surgical team have roles in verifying the correct site.

Jim King, attorney for the doctor and the hospital, declined to comment on the lawsuit.

Rudd’s isn’t the only wrong-site case making its way through the legal system in Spokane.

Jeffrey Girtz, 52, and his attorney, Stephen Haskell, haven’t filed suit and won’t name the hospital and doctors involved because they are negotiating a possible out-of-court settlement.

But they are willing to tell Girtz’s story. The Spokane real estate agent had a tumor on one of his adrenal glands. A surgeon removed the wrong one on July 28, 2003, causing Girtz to need a second surgery.

Now, with both his adrenal glands removed, Girtz must take hormones the rest of his life. He suffers headaches, insomnia, fatigue and nausea. He carries an emergency kit that contains a steroid injection. The kit could save his life if he suffers an attack caused by lack of the hormones the glands normally produce.

One of the odd symptoms of his condition is darkened skin, which makes him look tanned and healthy.

“Friends say, ‘Man, you look great,’ ” Girtz said. “I’m angry because I never feel good.”

Faulty systems

Medical errors are rarely caused by the doctor, said Wachter, the author. Faulty systems are to blame.

“Safety has been an afterthought in modern medicine,” Wachter said in a telephone interview. “We’ve been so busy with progress and technology and specialization that we forgot to make sure we could do this practice of modern medicine safely.”

That’s where the new rules come in. The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, an organization that accredits most U.S. hospitals and some outpatient surgery centers, issued the rules. The commission has been collecting voluntary reports of medical errors since 1995.

Wrong-site surgery is just one category of medical errors and unexpected events collected by the commission. Other categories include transfusion errors, medication errors and delays in treatment.

Wrong-site surgery errors are the third most frequent category of what the commission calls “sentinel events,” meaning those that cause unexpected death or serious harm. The most frequent categories are patient suicide (a problem in psychiatric wards) and complications during and after surgery. Wrong-site surgery incidents make up 12 percent of the total 2,552 events reported since 1995.

The commission issued alerts to its member hospitals about wrong-site surgery in 1998 and 2001. But wrong-site surgery errors continued to be reported at the rate of five to eight a month. So the commission convened an expert panel to write the new rules.

Some hospitals had their own rules for marking surgical sites. But because surgeons work at many hospitals, a universal protocol was needed.

In the Inland Northwest, some hospitals began instituting the Joint Commission rules more than a year ago. The commission’s board approved the rules in 2003.

Spokane’s four big hospitals formed a committee that meets to fine-tune how the rules are implemented. For eye surgery, the committee recently decided it was unnecessary for a surgeon to scrawl his initials on a patient’s forehead above the correct eye. A dot will do, the committee decided, said Denise Dominik, director of performance improvement for Sacred Heart Medical Center.

Some doctors have resisted the rules, Dominik said. Orthopedic surgeons were wholeheartedly behind the rules because their professional organizations had been pushing for them. But other specialists felt insulted.

Kootenai Medical Center in Coeur d’Alene instituted the rules about 18 months ago, said Dr. Joe Bujak, KMC’s vice president for medical affairs. The “time out” rule met with scoffing from some doctors, Bujak said.

“The biggest problem with the time out is the label ‘time out,’ ” Bujak said. “It sounds like something you do in preschool or day care.”

Some surgeons felt offended by the rules, Bujak recalled. “We heard the ‘captain of the ship’ objections. ‘Do you think I’m an idiot?’ ‘This is Mickey Mouse.’ ‘This is going to slow me down.’ “

By avoiding the phrase “time out,” and stressing that the pause before surgery is a way of affirming the interdependence of the surgical team, surgeons’ concerns were eased, Bujak said.

The new protocol “becomes a way of bringing focus of the people in the room to the task at hand,” he said.

Bujak said he could not recall a wrong-site surgery at KMC, but he does remember a near miss in 1997. An orthopedic surgeon made an incision for a joint replacement on the wrong side before recognizing the error.

Fairly rare

Patients, too, have a part to play in preventing medical errors, said Mark Forstneger, spokesman for the Joint Commission. If a patient or family member suspects something is amiss, it’s better to ask questions at the time, rather than later.

“Patients should not be afraid to speak up,” he said.

Wrong-site surgeries are considered fairly rare: One study suggests a rate of 1 in 15,500 surgical procedures. A survey of hand surgeons published last year found that one in five had operated on the wrong site at least once in their careers. The Joint Commission database of “sentinel events” voluntarily reported since 1995 includes 310 wrong-site surgery incidents.

The rarity of wrong-site surgeries has slowed the search for ways to fix the system, Wachter said.

“Cutting off the wrong leg doesn’t happen that often,” he said. “You could be a surgeon for 20 years and you’ve never had it happen, so you have the sense, ‘Why do I have to do all this stuff?’ “

He’s also heard medical folks argue that there’s no hard evidence that the new rules will make any difference.

He has a response.

“There was no evidence that barricading the cockpit doors after 9-11 was a good idea either. If you wait for the randomized study in the New England Journal of Medicine, a lot of patients are going to get the wrong leg operated on in the meantime.”