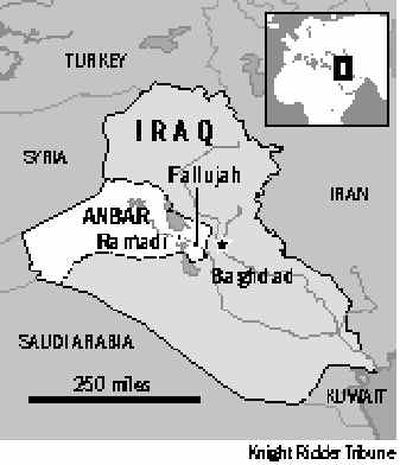

U.S. cedes territory in Anbar Province to rebels

RAMADI, Iraq – After more than a year of fighting, U.S. troops have stopped patrolling large swaths of Iraq’s restive Anbar Province, according to the top American military intelligence officer in the area.

Most U.S. Army officers interviewed this week said the patrols in and around the province’s capital, Ramadi – home to many Iraqi military and intelligence officers under Saddam Hussein – have stopped largely because the soldiers and commanders there were tired of being shot at by insurgents who’ve refused to back down under heavy American military pressure.

Asked for comment, officials from the 2nd Battalion 4th Marines in Ramadi – which makes up about one-fifth of the forces there – provided a 21-year-old corporal, who confirmed that the Marines have discontinued patrols, but said it was because of the hand-over of sovereignty to the interim Iraqi government.

While American officials in Ramadi wouldn’t provide exact figures for the change in numbers of patrols, there’s obviously been a significant drop.

After losing dozens of men to a “voiceless, faceless mass of people” with no clear leadership or political aim other than killing American soldiers, the U.S. military has had to re-evaluate the situation, said Army Maj. Thomas Neemeyer, the head American intelligence officer for the 1st Brigade of the 1st Infantry Division, the main military force in the Ramadi area and from there to Fallujah.

“They cannot militarily overwhelm us, but we cannot deliver a knockout blow, either,” he said. “It creates a form of stalemate.”

In the wreckage of the security situation, Neemeyer said, U.S. officials have all but given up on plans to install a democratic government in the city, and are hoping instead that Islamic extremists and other insurgent groups don’t overrun the province in the same way that they’ve seized the region’s most infamous town, Fallujah.

“Since Ramadi is the seat of the governate, we worry that if they could unsettle the government center here they could destabilize the al Anbar province,” said Capt. Joe Jasper, a spokesman for the 1st Brigade.

The apparent failure of a long line of Army and Marine units to bring peace to the province, which makes up about 40 percent of Iraq’s landmass, will be a major challenge for Iraq’s new government and could prove to be a tipping point for the nation as a whole. Increasingly, Iraq is a place in which cities or part of cities have been taken over by insurgents and radicals.

U.S. officers in Ramadi openly acknowledge that the Iraqi security force trained to take over the hunt for insurgents, the national guard, has become a site-protection service that so far is incapable and unwilling to conduct offensive operations.

When the governor of Anbar left town last month, the head of the national guard, who since has been replaced, took part in an attempt to overthrow him. National guardsmen in town have refused to go on patrols either alone or with the Americans. The 2,886 national guardsmen in Ramadi so far have detained just one person.

To show how operations in Anbar have changed, Jasper sketched a map on a piece of paper.

Pointing to a neighborhood outside the town of Habbaniyah, between Fallujah and Ramadi, he said, “We’ve lost a lot of Marines there and we don’t ever go in anymore. If they want it that bad, they can have it.”

And then to a spot on the western edge of Fallujah: “We find that if we don’t go there, they won’t shoot us.”

Marine Cpl. Charles Laversdorf, who works in his battalion’s intelligence unit, said the Marines averaged just five raids a month and no longer were running any patrols other than those to observation posts.

The sharp reduction in patrols flies in the face of comments made recently by a top military official in Baghdad, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“Any insurgent that … somehow thinks that after June 28 we’ll be pulling back into base camps will be disappointed,” he said. “This is a long-term program of handing over responsibility… . It’s not going to take days nor weeks, it’s going to be months and years.”

More than 124 U.S. troops have died in Anbar since President Bush declared major combat operations over in Iraq on May 1, 2003.

Between the 1st Brigade’s 4,000 soldiers, who arrived in Ramadi last September, and a battalion of 1,000 Marines, who came in February, more than 80 have been killed and more than 450 injured.

Since the hand-over of sovereignty June 28, 25 U.S. soldiers have been killed. Fifteen of them were in Anbar.

The numbers grow more striking at smaller unit levels.

Capt. Mike Taylor, for example, commands a company of men in nearby Khaldiya. Out of his 76 troops, 18 now have purple hearts, awarded for combat wounds.

The Marines’ Echo company, with 185 members, has had 22 killed.

“There’s a possibility that we’ll say we’ll protect the government and keep travel routes open, and for the rest of them, to hell with ‘em,” said Neemeyer, the intelligence officer. “To a certain degree we’ve already done it; we’ve reduced our presence.”

Neemeyer continued: “I’m sure they are beating their chests and saying they drove us out, but what have they driven us out of? Rural farmland that’s not tactically important. … If they want to call that victory, that’s fine.”

Looking up at a map on the wall, Neemeyer flicked his laser pointer across a large piece of land between Ramadi and Fallujah. “We don’t go into that area anymore,” he said. “Why go there when all that happens is we get hit?”

The U.S. military has poured about $18 million into reconstruction projects in Ramadi, but Neemeyer said the projects hadn’t done much in the way of winning people over.

“The only way to stomp out the insurgency of the mind,” he said, “would be to kill the entire population.”