Afghan artifacts safe after all

More than 22,000 treasures from the Kabul Museum in Afghanistan, long thought to have been lost in the war against the Soviet Union and the subsequent cultural purge by the Taliban, have been located in bank vaults and other safe places where they were hidden by museum officials.

The priceless Bactrian gold collection, precious ivories, bronze statues and other artifacts of 5,000 years of history on the Orient’s Silk Road – virtually all of the museum’s most precious items – were preserved despite the devastation engulfing the country, archeologists said Wednesday.

The discovery of the Bactrian gold was announced this summer, but a just-completed inventory revealed that virtually all of the museum’s most precious items are intact, said Oxford University archeologist Fredrik T. Hiebert.

In the midst of the resistance against the Soviets, a team of curators in the early 1980s boxed up the most valuable pieces in the museum’s collection, stashing them in various vaults around Kabul, the Afghan capital. The curators – most of whom are unknown – used small safes, tin boxes, steel containers and anything else they could find.

They then went “dead quiet,” said British archeologist Carla Grissman, keeping their knowledge to themselves even as rumors floated widely about the destruction and looting of the museum’s contents.

They kept their secrets for a quarter of a century.

“These are the real heroes of this story,” Hiebert said.

Because the once-missing artifacts come from so many different places along the Silk Road the find “has a significance well beyond Afghanistan and Central Asia. It’s of world importance.”

Now that the artifacts have been inventoried, they have all been packed up again and stored in a once-again secret location until the government can find a new home for them.

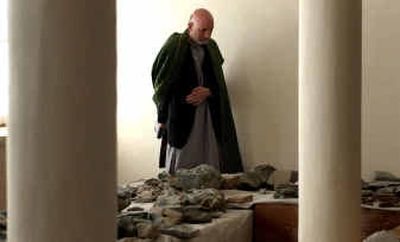

The Kabul Museum has been restored, but security there is not sufficient to protect the artifacts. Curators hope to build a state-of-the-art museum in central Kabul, but no one is sure where the money will come from.

The Afghan Ministry of Culture may organize an international tour for the collection in an effort to reestablish the country’s historical bona fides.

The Kabul Museum was a small facility housed in a 1920s-era federal building about 30 minutes outside the city center. Although it was small, Hiebert noted, “it is said that every piece (it had) was a masterpiece.”

Because it straddles the Silk Road that camel caravans used to transport textiles from China to Europe and pottery, artworks and other materials in the opposite direction, Kabul was a prosperous city throughout much of civilization’s early history.

As a result, the museum held objects from a string of civilizations that conquered or traveled through the region, including the Bactrians, Kushans, Greeks and Buddhists.

Unfortunately, the museum’s neighborhood became a frontline in the fighting against the Soviets and the building was shelled into a windowless, roofless hulk. Many of the artifacts that had not been removed were blasted to shards. More important, the inventory cards that described the museum’s contents were destroyed by fire and neglect.

That wasn’t the end of it. The victorious mujahedin broke open storerooms and looted much of what was left. Antique dealers in New York, Tokyo and London began displaying artifacts bearing catalog numbers from the museum.

The final indignity came with the Taliban regime, which smashed many of the remaining statues in the museum and destroyed the monumental Buddhas in Bamiyan. They tried to find the hidden treasures, but were unsuccessful.

Among the greatest treasures hidden away was the Bactrian gold, a collection of 20,457 golden objects excavated in northern Afghanistan in 1978 by Russian archeologist Viktor Sariandi. Excavating a crude burial mound not far from the city of Shiberghan, Sariandi found that the coffins, skeletons and clothes of the six occupants had rotted away, leaving behind a collection of near-pristine golden ornaments.

The collection included appliques from cloaks, figurines, clasps decorated with cupids riding dolphins, pendants depicting war scenes, a statue of the goddess Aphrodite and an elaborate crown.

After the gold disappeared during the early stages of the war, historians feared that it had been carried off to Russia or possibly melted down for its gold.

As it turned out, the Bactrian gold was stored in an elaborate bank vault along with much of the country’s store of gold bullion, protected behind a shield of seven locks that defied the efforts of the Taliban to break in. It was not until August 2003, when a team of locksmiths was brought in from Germany, that their location became known.

Hiebert was brought in this spring to catalog the gold with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Geographic Society. Using a portable laboratory carried in a half dozen suitcases, the team identified each piece, photographed it, cataloged it, and preserved it before packing it back away.

They found that every piece of the Bactrian collection, from medium-sized statues down to fingernail-sized slivers, was present and accounted for.

When Hiebert finished that task, he was surprised to be told there where some other boxes to be inventoried.

The team began opening them in August of this year. The first set of boxes contained 2,000-year-old ivories from the Kushan capital of Begram, intricately carved and engraved with scenes from palace life. Other boxes contained highly detailed glass goblets from Alexandria, Egypt, bronze statues and plaster busts of the elites from Rome and Belgram, and early Buddhist sculptures.

“It was a very emotional experience watching these men (Afghan archeologists) as they saw their own heritage coming back to life,” Hiebert said.

He said the team has now found and inventoried all but about a hundred of the most valuable artifacts from the museum. They have also recreated the original cataloging system, so that they know which items are missing from the collection. Armed with that information, international authorities may be able to retrieve many of the items from dealers and collectors, he said.