Little brown-haired girl from Idaho has touched us all

The day was perfect as the Harley Owners Group convened for its monthly meeting and ride. Within 30 minutes, the planned ride was scrapped and a new route chosen,

“I charted three different routes so we could make it to Cruiser’s,” said Road Capt. Gabe Fernos, a burly ex-Army sergeant. His Puerto Rican accent added flavor to his words. “I figured it was the least we could do” to show support for Shasta Groene and her family.

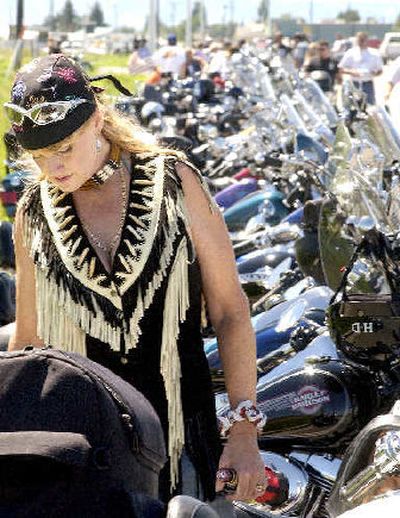

He mounted his bright yellow Electra Glide, denim vest covered with patches and pins and pulled to the head of the group, which left from the North Side Eagles Lodge and took a winding route though North Idaho before arriving at Cruiser’s, in Stateline, Idaho, last Sunday.

Two miles of bike chrome gleamed in the sun at the small bar. Police cars were parked in the entryway but the cops were glad to be there just like the rest of us. After all, this was a combination of states and communities trying to cope with the unthinkable and support a little girl who has a world of hurt to work through.

By now, most are aware of what happened one night to the Groene/McKenzie family – three people were killed. Shasta and her brother, Dylan, vanished. Communities were shaken; parents came under a new siege of fear. And pictures of Shasta and Dylan were everywhere, their impish grins peeked out with eyes full of childlike wonder.

Days turned into weeks. Most suspected the worst but hoped they were wrong while local and federal law enforcement tracked leads.

Seven weeks later, Shasta, an 8-year-old with long brown hair, is the sole survivor. Nine-year-old Dylan’s remains found in a remote Montana campsite near the Idaho border.

Shasta didn’t see Sunday’s outpouring of community support, but that didn’t stop our instinctive desire to help when the defenseless are injured.

She didn’t see the Red Hot Mamas dancing to “We are Family,” nor the Hooters staff washing cars and bikes, the hundreds of donated items for the silent auction, the spaghetti meal provided by Luigi’s, the miles of bikes, hot rods and minivans, the plethora of biking leather and baby strollers all convening at one small biker bar to wish her well, to let her know we’re here for her in the only way we know how – by our presence.

“God’s blessing and our prayers to Shasta and her family,” one sign read. “Welcome home Shasta,” another said in bold black letters.

People took donations and a band played while the Cruiser’s crew worked their tails off to keep the food and beverage flowing. Pictures of Shasta were scattered throughout the silent auction tables, reminding bidders why they were there.

Right now, Shasta doesn’t realize how distressed the community was when she and Dylan disappeared, how they pulled together to find them by watching and calling the police when she walked into a Coeur d’Alene Denny’s, looking apprehensive and accompanied by a monster disguised in human skin, but perhaps one day, when this tragedy recedes, when her mind is free from fear, she’ll know how many lives she touched.

She’ll also know what we, as a community, did to protect her and others.

In the meantime, we’re here, Shasta, and that’s the best we can do for now.