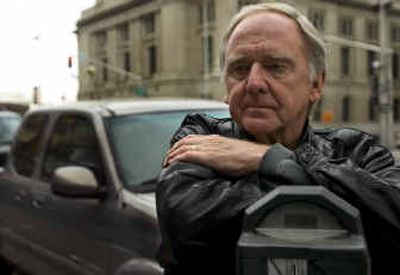

Investor seeking answers

Gerry Hanson stands to lose more than $1 million in the Metropolitan Mortgage & Securities fiasco, and he wants some answers.

Hanson, who lives in Sparks, Nev., was recovering from prostate cancer when the company he entrusted much of his money with began to stumble.

He was too sick to ask questions then. As one of the largest creditors in Metropolitan’s bankruptcy case, he might even have qualified for a seat on the official creditors’ committee.

He did write a couple of letters explaining his medical condition and asking the company to refund his investment to ease the sting of medical bills.

“I didn’t even get a reply,” he now says.

Feeling better now, Hanson, 67, drove his silver Toyota pickup to Spokane last week and began asking questions.

He spoke with lawyers, met with company officials, called other investors and scoured Bankruptcy Court records. He plugged a small fortune into downtown parking meters.

Within days he had filled a notebook with names and numbers. What he learned transformed disbelief and frustration into anger: He has more than $700,000 invested in Metropolitan bonds, and $500,000 more sunk in sister company Summit Securities Inc.

“We got taken,” he says, “and I’m not too happy about it. Somebody better pay.”

At least one person involved with Hanson’s loss will.

Hanson’s broker, Theodore R. Metoyer, of Spokane, settled charges this week that he made unsuitable investment recommendations. The consent decree, according to the state Department of Financial Institutions, includes a $5,000 fine, but more importantly, permanently bars Metoyer from working as a licensed broker or investment adviser in Washington.

Hanson’s story is like that of many other investors. Metropolitan was his sure thing – the safe investment handed down to him from decades of family investing.

His grandfather farmed near Hayford, west of Spokane, and began investing in Metropolitan in the early 1950s. He personally knew the company founder, the late Paul Sandifur Sr. Some of that investment was passed to Hanson’s mother, who recently died, and then on to Hanson, who says that as he continued to buy unsecured bonds called debentures, he never knew that the company had changed from a thrifty outfit buying discount mortgages into a risk-taking firm deeply into commercial real estate.

The sense of security seemed so sure that Hanson urged relatives and friends to buy bonds. He now feels sick about what’s transpired, he says.

His trip to Spokane is part of a puzzle. He won’t have peace of mind until he figures it out.

“How could this have happened?” he asks. “Didn’t anybody know? Wasn’t anyone watching? Who is to blame?”

All are nagging questions for the more than 16,000 people who invested in Metropolitan, which first sought bankruptcy protection in early 2004 after an auditing scandal began exposing a series of questionable practices.

Hanson is no rube. He went to Spokane schools and graduated from Gonzaga University. He spent 35 years with pioneering computer company Control Data Corp., once heading up the firm’s international sales division. His eyes still light up when he talks about how he helped sell supercomputers to the U.S. military in the early 1960s that were so big they wouldn’t fit inside the living room of most houses.

Today, he says with a laugh, such processing power can fit inside a shoebox.

He recalls once teaching the faculty of the Stanford Research Institute about the computers.

The job just about killed him. Hanson had his first stroke while trying to sell a blockbuster computer package to the Japanese government many years ago.

A second one followed when he returned to work too quickly.

He had been enjoying his retirement and grandchildren when he nearly succumbed to prostate cancer in 2003. By early 2004, doctors had planted hundreds of so-called irradiated seeds to combat the disease.

The doctor told him that if he made it a year, he would easily make it 10 more.

So here he is, tromping around downtown Spokane searching for elusive answers as windstorms blow the sky brown with dust from barren farm fields. “Lovely town you’ve got here,” he remarks.

But he knows he’s a year late, as Metropolitan prepares to release a new liquidation plan, the second since it filed for bankruptcy 13 months ago. Hanson says he wishes he could rewind the clock.

“I got here as soon as I could,” he says, “and now I’m just so appalled about everything.”

He rattles off a list of grievances that includes everything from alleged securities fraud and bogus real estate dealings, to expensive bankruptcy lawyers.

“I think as investors we’ve all been lied to so much that we don’t know what to believe anymore,” he says.