Murderer now fights for his life

Nine years ago, Faron Lovelace just wanted to be put to death.

A federal fugitive captured by the FBI near Priest River, Idaho, in 1996, Lovelace couldn’t stomach the thought of more prison time. He’d spent much of his adult life behind bars for a variety of crimes – stealing cars, armed robbery and escaping from prison.

So he confessed to murdering a fellow racist and led authorities to the body of 23-year-old Jeremy Scott, buried in the upper reaches of the Pack River in the shadow of Chimney Rock.

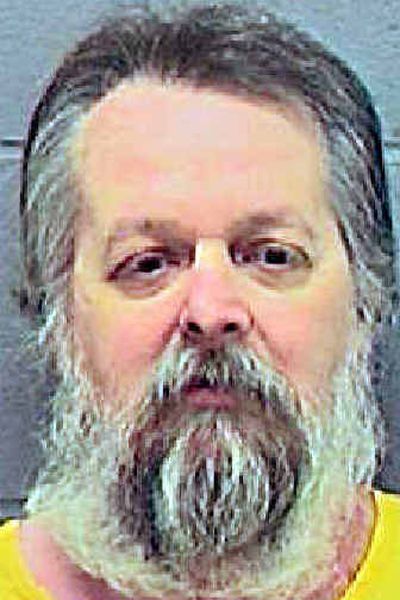

He got his wished-for death sentence in 1997, but now Lovelace, 48, is back in the Bonner County Jail awaiting retrial before a jury. The latest court action follows a U.S. Supreme Court decision that all death sentences must be handed down by juries, not judges.

Lovelace must be resentenced by jury. And this time, he plans to fight for life, even as he expresses ambivalence about living.

“I don’t care – I’m dying anyway. I’ve got diabetes,” he said during a recent jail interview, showing off sores on his ankles and toes caused by the disease.

His change of heart seems motivated by a need to escape the endless days in a 10-by-12-foot cell on Idaho’s death row, whether by death or by entering the general prison population, and a desire to spite a deputy attorney general with a Jewish-sounding name: Jay Rosenthal.

“Now I want Rosenthal to lose,” he said.

Meanwhile, back in Pennsylvania, Scott’s younger half sister prays for another death sentence for Lovelace, and is planning to buy a plane ticket to attend the September trial.

“He’s done irrevocable harm to our family,” said Kathryn Main. After learning of the murder, Scott’s father sank into depression and Scott’s grandmother became so ill she nearly died, Main said. And Scott’s infant son, Hansel, was left fatherless.

“Jeremy had a lot of ideologies that I didn’t agree with, but when it came to being a father, he was excellent,” Main said. “He just adored Hansel.”

Crime and racism

Lovelace passes time in jail reading his Bible, clipping photos of white people out of the newspaper – a collection of “beautiful people,” to the self-described racist – and trying to decide whether to represent himself in his upcoming trial.

He’s been recently weaned from drugs to treat depression that he said was the result of spending years on death row, where he was isolated in his cell for 23 hours a day. Once he tried suicide, slashing his arms and ankles with a homemade knife of razors.

“Imagine the room you’re in. There’s one window, just a little gash,” he said.

Without the drugs, he says he’s hyper-vigilant, and has difficulty keeping his train of thought. While at the maximum security prison south of Boise, Lovelace shaved his face and head for hygienic reasons, but now he’s letting his hair grow and has a gray beard that curls under his chin.

Lovelace grew up in a decent family, he said, but never spent any time around people of other races until he joined the Army in 1974. While in the Army, he said, he was beat up by some black men. Later, while spending time in prison, he had more run-ins with African Americans and his racist views deepened.

By the time he was paroled in 1994, following an armed-robbery conviction, he decided he wanted to spend the rest of his life as an “activist” for the white race, which he fears is disappearing.

“I was willing to lay down my life for the white race,” he said. “I was going to train myself to be an assassin.”

Lovelace skipped out on parole, and was hiding out at Elohim City, a white-supremacist community in Oklahoma, when he met Chevie Kehoe. He joined Kehoe, who was heading to the Inland Northwest, he said.

Kehoe now is spending life in prison for murdering a family in Arkansas, but is implicated in many other crimes, including the 1996 bombing of Spokane City Hall. His brother, Cheyne, was sentenced to 23 years in an Ohio prison following a shootout he and Chevie Kehoe had with law officers there.

Lovelace collaborated with Chevie Kehoe on some crimes in the Inland Northwest, including the kidnapping and robbery of Colville business owners Malcolm and Jill Friedman, who were allegedly targeted because of their Jewish names.

Both Kehoe and Lovelace were acquainted with Jeremy Scott, a young skinhead who came to the Inland Northwest with his girlfriend, Kelly Kramer, in 1993.

Scott disappears

Main recalls getting letters from her brother after he moved to Idaho. He lived with Kramer up the Pack River, first in a bus and later in a cabin.

“He talked about how beautiful it was there and the ability to live on your own and not have a lot of interaction with people,” she said. Scott’s family knew he was involved in the white-supremacist movement, but it wasn’t something they discussed with him – preferring not to know, she said.

Scott’s mother was only 16 when he was born, and left him when he was 18 months old, his sister said. His stepmother, Main’s biological mother, was bipolar and abusive toward Scott, Main said. Her father remarried after a bitter divorce and custody battle.

“He had a pretty crappy go of it,” Main said. “That’s probably what attracted him to the skinhead movement. They really target that angry white male who comes from a rough background.”

Shortly before he was murdered, Scott confided in his dad that he feared Lovelace was going to kill him, Main said. By then, Kramer had moved out with their baby, Hansel. She had left Scott before, and claimed Scott abused her. She eventually moved in with Chevie Kehoe in a polygamist relationship as his second wife.

“He (Scott) missed his son and didn’t know where Kelly and Hansel were,” Main said.

When Scott disappeared in 1995, his grandmother feared the worst. She sent him a box of brownies, but knew that he never picked them up from the post office.

“She had a bad feeling. She knew for a long time,” Main said. “The rest of us hoped he would be OK.”

Confessions of a killer

Lovelace has told a couple different stories for why he killed Scott.

Early on he told authorities that he thought Scott was a government informant who might reveal a plot to assassinate then-Sheriff Chip Roos and other officials. According to Bonner County Sheriff’s Lt. John Valdez, Lovelace later said that Kehoe, who wanted Kramer as his wife, wanted Scott out of the way.

Lovelace has more or less stuck to the story he told at his 1997 trial, that he killed Scott to save Kramer.

After Kramer left Scott, he said, “Jeremy became the hunter.”

Lovelace said he was waiting for Scott and dressed in camouflage the summer evening in 1995 when he surprised Scott at gunpoint near his cabin. Telling Scott that Kramer, his son and others were coming to meet with them, he had Scott drive up toward the upper end of the rugged Pack River Road with him and wait, he said.

“He was waiting for his son. He received a bullet,” Lovelace said during his trial.

Law enforcement authorities didn’t know Scott was missing until Lovelace led them to the body after being arrested for skipping out on parole, Valdez said.

Lovelace still admits to the murder and describes himself as an evil man; “I deserve to be destroyed or worse,” he said.

He was convicted of both first-degree murder and second-degree kidnapping, but now he’s trying to beat the kidnapping conviction, which makes the murder a capital offense.

The attorney general has filed a notice of intent to seek the death penalty.

Lovelace said the attorney general’s office rejected a plea proposal in which he would plead guilty to murder, the kidnapping charge would be dismissed and he would spend life in prison without parole. Attorney General spokesman Bob Cooper said he could not confirm nor deny the plea proposal, saying that discussing any alleged plea agreement would violate professional conduct rules.

Lovelace, who has now spent 27 years in jail or prison, is now fighting to spend the rest of his life there.

“They cannot possibly prove kidnapping,” he said. “I’m the only witness.”