Copyright dilemma

BOSTON — It’s been the better part of a decade since Napster and other free song-sharing services began scaring the daylights of the music industry. And still recording companies can’t find an effective anti-piracy technology to save their hides.

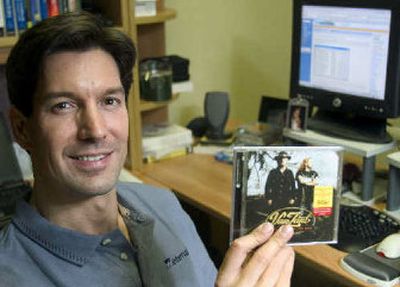

The fact that so-called digital rights management might always be a doomed experiment became painfully clear with the fiasco that erupted after Sony BMG Music Entertainment added a technology known as XCP to more than 50 popular CDs.

After it was discovered that XCP opened gaping security holes in users’ computers — as did the method Sony BMG offered for removing XCP — Sony BMG was forced to recall the discs this week. Some 4.7 million had been made and 2.1 million sold.

Factor in lawsuits that Sony BMG could face, and it’s worth wondering whether the costs of XCP and its aftermath might even exceed whatever piracy losses the company would have suffered without it.

That’s not even accounting for the huge public relations backlash that hit Sony BMG, the second-largest music label, half-owned by Sony Corp. and half by Bertelsmann AG.

“I think they’ve set back audio CD protection by years,” said Richard M. Smith, an Internet privacy and security consultant. “Nobody will want to pull a ‘Sony’ now.”

Phil Leigh, analyst for Inside Digital Media, said the debacle shows just how reluctant the labels are to change their business model to reflect the distribution powers — good and bad — of the Internet. He believes that rather than adopting technological methods to try to stop unauthorized copying of music, record companies need to do more to remove the incentive for piracy.

“The biggest mistake the labels are making is, they’re letting their lawyers make technical decisions. Lawyers don’t have any better understanding of technology than a cow does algebra,” Leigh said. “They insist on chasing this white whale.”

It’s easy to understand why the music industry wishes songs could magically be prevented from being ripped from CDs and shared freely.

The industry has seen an estimated $2 billion overall decline in CD sales in the last five years. New digital services such as Apple Computer Inc.’s iTunes have made up some of that, but still account for just 6 percent of the industry’s global sales.

The challenge has been to find an anti-piracy tool that works well enough to please the industry without overly annoying users, many of whom want to make legitimate backup copies of their CDs and don’t like being assumed to be criminals.

The anti-piracy methods that have been attempted are legion, some rather low-tech. For a while recording labels commonly sent music critics promotional material in portable players glued shut to prevent copying.

For the broader audience, new discs emerged that included digital watermarks — extra encoding designed to lock the recordings, or at least their high-resolution portions — on the disc.