Rumsfeld seeks an old friend

WASHINGTON – In August 1956 a newlywed Navy pilot, Lt. James B. Deane Jr., was shot out of the sky on a nighttime spy flight off the coast of China. Nearly half a century later, a famous friend found himself in Beijing with a chance to quietly press Chinese leaders for more cooperation in resolving Deane’s fate.

The friend was Donald H. Rumsfeld, the defense secretary known for hardline views on communist China. He and Deane were fellow Navy fliers and became buddies while stationed together in Florida in 1954 and 1955.

Rumsfeld’s personal connection to the Deane case is a coincidence of history not publicly reported until now.

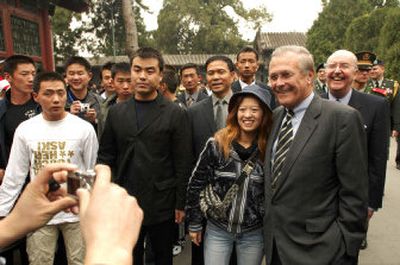

The chief focus of Rumsfeld’s visit to Beijing last October was his concern about China’s military buildup. Privately, he also made a point of urging Chinese officials to look further into the Deane episode. Like other efforts he made on behalf of Deane’s widow before becoming defense secretary, his urging yielded no new answers.

The Cold War case has been clouded in mystery and secrecy since the Martin P4M-1Q Mercator in which Deane and 15 other men were flying was shot down over the East China Sea shortly after midnight Aug. 23, 1956. Rumsfeld raised it while also seeking more Chinese openness on all cases of missing U.S. servicemen.

“I remember the good times with him and remember the sorrow of losing him,” he said of his friend in an interview.

China has acknowledged that its jet fighters attacked the Mercator as it scooped up electronic intelligence on military radars and other sensitive Chinese systems. But China repeatedly has denied knowing Deane’s fate.

The remains of four crew members were recovered – two by the crew of a U.S. search vessel and two by China, which returned the bodies through British authorities in Shanghai. The other 12 were never found. Adding to the mystery were unconfirmed U.S. intelligence reports, in the months after the plane was shot down, that Deane and perhaps one other may have survived the crash and been taken to a Chinese hospital.

A March 4, 1957, report by the 6004th Air Intelligence Service Squadron said two survivors of the Mercator attack had been moved in late November to the residence of a Chinese government official. Identifying information for one “appears to fit the description of Lieutenant (junior grade) James Brayton Deane, Jr.,” said the report, which was declassified in 1993.

The Rumsfeld-Deane link is the only known instance of a secretary of defense, whose official duties include overseeing U.S. government efforts to account for missing-in-action servicemen, having a personal link to an MIA involving China. It is a coincidence that Rumsfeld has kept out of the public spotlight in deference to Deane’s widow, Dr. Beverly Deane Shaver, who until now had pursued the matter strictly in private.

Now Shaver is going public, eager to express her gratitude for Rumsfeld’s support and correct what she believes has been a false U.S. government characterization of her first husband’s fate.

“He was declared missing, when I’m 99.9 percent certain he was not. He was alive,” she said in a telephone interview from her home in suburban Phoenix. “It almost makes a person’s life a lie, and that really bothered me.”

Deane was 24 years old.

“He was a big man, physically, and had a good smile and enjoyed life,” Rumsfeld said in the interview. “As an aviator he was a very serious person. He was a fine, enjoyable person to be around.”

A year after the plane was shot down, the Navy told Shaver that Deane was presumed dead, based on an absence of evidence that he was alive. Shaver, however, now feels she has seen enough evidence – including declassified intelligence reports – to conclude that he likely survived the attack, if not a subsequent detention.

She and Deane were married May 19, 1956, and were living near Iwakuni Naval Air Station in Japan when her world suddenly collapsed. She recalls a Navy chaplain arriving at their home unannounced the morning of Aug. 23. And she recalls thinking then of the words her husband had often used to calm her fears for his safety.

“You don’t have to worry about me flying,” he would say. “You only have to worry when you see a chaplain at the door.”

Over the years, Rumsfeld avoided speaking publicly in detail about Deane, although he mentioned his name in a speech five years ago.

That occasion was a ceremony honoring the crew members of a Navy EP-3E Aries surveillance plane that collided with a Chinese fighter jet in April 2001 near Hainan Island. Though that crew survived and was released from Chinese custody after being held for 11 days, the incident offered haunting parallels to the Deane case.

Both involved an electronic surveillance mission gone awry and both touched Rumsfeld – the first in a deeply personal way.

At the moment he spoke Deane’s name at the Andrews ceremony – “the co-pilot was a close friend of mine,” he began – Rumsfeld says he pictured the 24-year-old’s face. When Rumsfeld noted that 47 men from that same squadron had been lost during the Cold War – including 31 in an April 1969 attack by a North Korean fighter jet – he visibly choked up.

Deane’s link to Rumsfeld had its roots in Grand Rapids, Mich., Deane’s home town. A high school friend of Deane’s, Jon Parrish, went on to Princeton, where he met and became friends with Rumsfeld. Deane attended Cornell.

All three were enrolled in their universities’ Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps programs and after graduating in June 1954 they wound up together in Pensacola, Fla., where freshly minted officers take flight training.

Both Parrish and Rumsfeld were married. Deane was not. When Shaver, whom Deane met at Cornell, came to visit him in Pensacola, she would stay at the Rumsfeld’s house, and she kept in touch over the years.

In late May 1956, just days after his wedding, Deane headed to Japan with his Mercator squadron. It was a time of tension between Washington and Beijing, which suspected U.S. efforts to destroy the communist regime that had seized power in 1949. The U.S. military regularly flew electronic surveillance missions off the Chinese, Soviet and North Korean coasts.

Richard Haver, a former senior U.S. intelligence official and Navy officer who looked into the case at Rumsfeld’s request in the late 1990s, said the Navy’s original investigation concluded that the Mercator’s nosedive into the sea was an “unsurvivable water entry.”

“Chances are really pretty slim” that Deane or any other member of the crew got out alive, Haver said in an interview.

Haver reviewed U.S. intelligence records of the case and interviewed former Mercator pilots. He concluded that Deane’s fate may never be known.

U.S. officials believe the Chinese government knows more about the matter than it has said, which is very little.

Rumsfeld has had a hand in quiet, inconclusive U.S. government inquiries about Deane since 1974, when Rumsfeld was chief of staff to President Ford. At that point, just two years after Washington began to normalize relations with the communist government in Beijing, the Ford administration was using the diplomatic opening to press for information about Deane and other MIA servicemen.

“The Chinese had informed us privately that they, themselves, hold no American servicemen,” Henry Kissinger, then the secretary of state, wrote in a declassified memo in January 1975. “They said they had as yet found no bodies nor had they turned up any other kind of information,” but were still investigating.

When Ford met Deng Xiaoping in Beijing in December 1975, the future top Chinese leader gave Ford a memorandum that said, “The Chinese side has no information on what happened” to Deane and the other 11 missing members of his crew.

Subsequent inquiries by U.S. officials – including Rumsfeld’s last October – produced essentially the same response from Beijing: We’ve looked again and found nothing.

Shaver, who has made two trips to China in search of answers, said that in 1999 she had indirect contact with a former head of China’s air defenses in the region where Deane was shot down. He recalled the attack and said two pilots had survived. But when pressed more directly he would not repeat the claim of survivors.

Shaver has not discussed the matter directly with Rumsfeld, but says she knows he raised the matter in Beijing.

“Rumsfeld was very compassionate on this,” she said.