Best duck callers know when to shut up

Roger Reynolds, former Western duck-calling champion, competes in only one type of duck-calling contest nowadays – the kind that’s judged by ducks.

When the Washington waterfowl season opens next weekend, the Nine Mile Falls hunter plans to sweet-talk Columbia Basin mallards into his decoy spread. It’s a language he mastered even before he began his 37 consecutive years of waterfowl guiding.

“I specialize in ducks,” he said. “I just prefer duck hunting. Ducks are quicker than geese. I like the way they move around. I love duck hunting, and the people I hunt with love ducks.

“Duck hunting isn’t the big production with all the decoys and special blinds you need for geese. I’m more mobile. I hardly ever hunt in the same place two days in a row.”

Reynolds said he learned to work a duck call at the age of 11 in the Columbia River sloughs near Westport, Ore. He mastered the art as a college student with personal tutelage from Howard Wood, the 1958 Oregon duck-calling champ.

While teaching radio-TV broadcasting at Central Washington University, Reynolds studied the sounds of hen mallards using tape recordings and voice prints. In 1970, he won the Western National Duck Calling Championships.

“That was at a time when judging was based on how close you sounded like a real duck rather than the stylized musical instrument-type calling exhibited in contests today,” he said.

“I’ve won contests and I know what winning is. I’ve done it and judged it. My hat’s off to the guys who are winning calling contests now. They’re good. But it’s more of a stylized thing. I don’t even like judging for that reason.

“If you can’t do the Arkansas ring, you don’t have chance of winning a calling contest, even though no duck makes that sound. It’s getting silly.”

Reynolds takes his duck hunting seriously, too. He has records for every hunt and scouting trip in his career of hunting the Columbia Basin.

“Now when I go scouting, it’s more confirmation of what I thought was the case rather than looking for birds,” he said. “But the hunting does change every year, depending on crops, water levels and weather.”

The most successful waterfowl hunters don’t hunt every day of the season,” he said. “You have to spend time just looking. That essential element keeps guides in business, because most people don’t have the time for scouting.”

Yet with all his experience, Reynolds confessed he still doesn’t know why ducks fly 10 miles, passing numerous cornfield smorgasbords, before they finally pick one field and land.

“If somebody knows, please give me the answer,” he said.

Reynolds keys on mallards because they are a favorite of hunters and they are the most responsive to calls. “Gadwall, pintails and teal are less predictable,” he said.

The most common mistake he sees among duck hunters has nothing to do with calling:

“A lot of guys don’t give enough attention to being properly concealed,” he said. “Smart mallards won’t come in if they detect you, no matter how well you call.”

The most common calling error he hears involves what he calls “blowing into a duck call. “You don’t blow into a call,” he said. “You talk into it.

“On opening day, and when northern birds first come into this area, they’ll respond to almost anything. But generally that lasts for only a few days. Ducks get wise to poor calling because they hear so much of it. It’s probably better to avoid calling if you don’t do it well.”

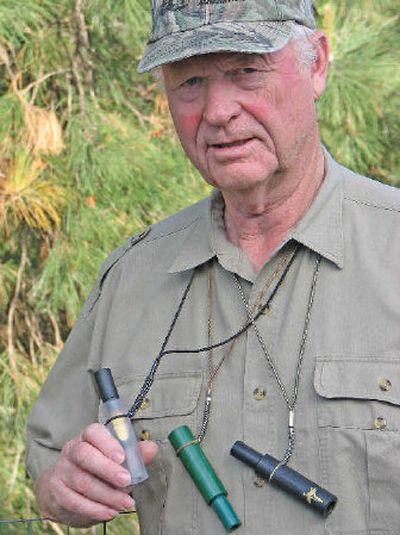

Since 1960, Reynolds has preferred KumDuck Calls, which have been made in Oregon since 1950. “I can make all the sounds ducks want with one call,” he said. “I don’t need a chandelier of calls hanging around my neck.”

Stores offer many good choices for calls, he said: “I like a get-down-and-dirty sound like you hear down in a marsh.”

Even good call artists can error by calling too much, he said.

“It’s easy to get desperate if the birds are going away, but if you lean on them they get suspicious,” he said. “During a hunt, I made a 90-second recording for my class materials when I was teaching duck-calling classes. I surprised myself at how many intervals there were.

“Sometimes you have to manipulate ducks into the pocket for a good shot. If you talk to them too soon in those situations, they might fly over you at tantalizing range and they might spot you.”

Decoy arrangements are important for giving a duck caller credibility and lure ducks to land within shooting range. But Reynolds believes calling can sometimes be an even stronger attraction than decoys. He’s put this theory to the test by noticing what ducks do if he’s out away from the blind looking for a bird when he spots a flight.

“More often than not,” he said, “the ducks want to come to the call, not the decoys.”

Reynolds is a minimalist with decoys. “There’s such a thing as overkill,” he said. “Anything more than 50 and you’re inviting bids to land wide. I’m not putting anybody down for using 200 decoys. I just don’t think you need that many.”

Opening weekend is perhaps the most dependable weekend of the year for duck hunting in Eastern Washington, he said. “Being a guide, however, I have to come up with good hunts from one end of the season to another,” he added.

“Bad weather days can be good for duck hunting in the right places, but I think blue-bird days are the best conditions almost anywhere for a good caller.”

Contact: Roger Reynolds, duck-hunting guide service, (509) 998-2395, or 276-8272.