Confronting child abuse

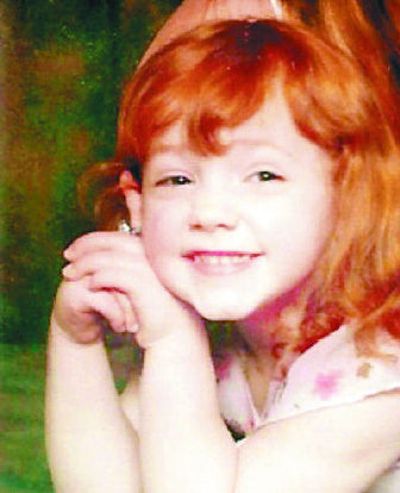

Before she became Spokane’s most horrific example of abuse in recent memory, Summer Phelps was an invisible child.

No one recalled much about the girl with the red hair and brown eyes who lived with her father and stepmother in the cramped Dresden Apartments on Spokane’s North Monroe Street.

Neighbors saw nothing wrong with the child who rarely ventured beyond the door of apartment No. 25. State social workers, warned last year about possible neglect, found no evidence. Because she was only 4, Summer was not yet in school, where a teacher might have noticed the burns and the bite marks and the bruises before it was too late.

Instead, the horror that was Summer’s short life became evident only after her death.

On March 10, the 3-foot-6-inch, 45-pound girl was brought to Deaconess Medical Center with injuries severe enough to keep veteran Spokane police Sgt. Joe Peterson awake at night.

Police said the girl had been routinely tortured and forced to pick up garbage and scrub soiled clothing and bedding at all hours. She had been shocked with a collar designed to quiet barking dogs, dunked head-first in dirty bath water and smothered with urine-soaked clothing.

Summer’s father, Jonathan D. Lytle, 28, and her stepmother, Adriana Lytle, 32, remain jailed on homicide-by-abuse charges.

“This case is beyond comprehension, what they did to this little girl,” Peterson said.

Just as disturbing, however, is that such abuse went undetected in the heart of a community that prides itself on being a good place to raise kids. Inland Northwest advocates who work with abused and neglected children say that Summer’s death is only the most extreme evidence of the kind of harm that affects thousands of youngsters in Eastern Washington and North Idaho each year.

“Those are the ones you read about, you hear about, but kids are beaten every day in cities across the country – and in Spokane,” said Karen Winston, a program supervisor at Partners with Families and Children, a social services agency. “I wouldn’t want anyone to think this is an isolated incident.”

Raising awareness about the reality of the problem, detailing its effects on children and families, and offering community solutions for the future is the subject of a monthlong series by The Spokesman-Review that begins today.

Although the April project was planned long before Summer’s death, experts said the loss of the child underscores the need for individuals and agencies to re-evaluate the way they think about – and respond to – abuse.

“It seems even more tragic when you think it didn’t have to happen,” said Joan Sharp, executive director of the Washington chapter of Prevent Child Abuse America, a national advocacy group.

Perhaps, she said, the shock of Summer’s death will become a turning point for community action.

“We’re trying to inspire and galvanize or open that sense of possibility at the individual, family and societal level,” Sharp said.

Few children die from injuries directly tied to abuse, records show. On average, 20 cases of unexpected fatalities in young people under age 18 are considered by Spokane’s Child Death Review Committee every year, said Cathy Fritz, a public health nurse who heads the program. Of those, perhaps three are ever tied explicitly to abuse.

“But in the background of the family unit, there’s a lot of it,” Fritz said. “There’s a lot of it.”

Washington state Department of Social and Health Services records show that nearly 4,200 children in Spokane County were named as victims of physical abuse, sexual abuse or neglect in cases accepted for investigation in 2005. In Spokane, that was a rate of about 40 victims of abuse for every 1,000 children ages birth to 17, advocates said.

Last year, Washington Children’s Administration officials received 4,014 referrals in Spokane County from people concerned about children being abused. About half of those were accepted for further investigation, said Nicole LaBelle, a program manager with the agency. The rest either were turned over to law enforcement or other agencies for action, or were dismissed for lack of evidence.

In the five counties that make up North Idaho’s Panhandle, 619 referrals were received in the fiscal year that ended last June, according to records of the state Department of Health and Welfare. Of those, about 27 percent were verified, and about 65 percent were classified as “unable to determine” or left blank. The rest were deemed invalid.

Local statistics generally match national breakdowns for types of abuse inflicted on kids, LaBelle said. About 10 percent of all abuse cases involve children who are sexually abused, most often by people they know and love. An additional 15 percent are physically abused, hurt in ways including beatings, burns, choking – and worse. The vast majority – more than 70 percent – are victims of neglect severe enough to present a danger to the child’s health, welfare and safety.

Although recorded instances of abuse and neglect number in the thousands in our region, experts agree it’s likely they are a fraction of actual incidents in the Inland Northwest, where child abuse remains a hidden problem.

“Abuse of a child is a dirty little thing,” said Connie Lambert-Eckel, a deputy regional supervisor with the DSHS. “You have families turning away from what they don’t want to see.”

The problem isn’t that people don’t know child abuse exists, said Sharp, of Prevent Child Abuse America. Focus groups conducted by the agency in the early 1980s and again two decades later showed that nearly 100 percent of respondents recognized all types of child abuse as a serious problem nationwide.

The trouble occurs when people are asked to translate the national concern to their own neighborhoods.

“They believe abuse and neglect happen to someone else,” Sharp said.

That’s as true in the Inland Northwest as anywhere, said Lambert-Eckel, who frequently encounters people who believe that child abuse occurs only in the poorest areas of Spokane.

“There’s this idea that those are bad neighborhoods and that poor people produce neglect,” she said. “But I’m looking at some of the upper South Hill ZIP codes and there are referrals. There’s no doubt about it. … We just don’t believe as an agency that kids are not abused on the South Hill.”

Child abuse allegations were recorded in every community in Eastern Washington, a ZIP code analysis of 2006 referrals showed, although they are more common in areas of lower income and limited education.

The largest number of referrals – 666 – came from the 99207 ZIP code, the Hillyard-area neighborhood where median family income hovers at about $30,000 annually and less than 9 percent of residents have a college degree, according to census figures.

By contrast, there were 44 reports of abuse in the 99203 ZIP code in one area of Spokane’s South Hill, where median family income tops $60,000 a year and nearly a quarter of adults have bachelor’s degrees.

Advocates here and across the country generally agree that child abuse and neglect is a vastly underreported problem, with two additional incidents of abuse for every one officially recorded, according to Fight Crime: Invest in Kids, a national nonprofit advocacy group.

Spokane-based studies suggest that nearly 20 percent of all children – one in five – live with violence, said Roy Harrington, a former DSHS regional director who is now a senior research associate at Washington State University.

“The incidence of family violence in this community is stunning,” Harrington said.

A 2004 WSU study of 3,200 Spokane residents showed that about 43 percent of women and 22 percent of men reported encountering intimate partner violence in their lifetimes. National figures vary widely, with estimates of violent contact ranging from 9 percent to 30 percent for women and 13 percent to 16 percent for men. By any measure, Spokane exceeds those levels, researcher Christopher Blodgett noted.

It’s not clear why violence may be more common here, but Harrington believes that more families here face multiple problems that contribute to crisis.

“When you stack poverty, family violence and mental illness on the same stack, you are creating probabilities that we cannot ignore,” he said.

Families in more affluent areas might be isolated from poverty, but it doesn’t mean they’re immune to abuse, advocates said.

Stephanie Leek, a veteran counselor at Holmes Elementary School in one of Spokane’s poorer neighborhoods, was openly skeptical of figures that showed there were 10 referrals for child abuse or neglect in Liberty Lake’s 99019 ZIP code in 2006.

“Only 10?” said Leek, laughing. “You know good and well that it’s far more than that.”

A lifelong Spokane resident who lives in the middle-class 99223 ZIP code neighborhood, Leek said social pressure contributes to the lack of reports in economically comfortable areas.

“The message is: We have a good family, a solid family. The pressure to appear to be a middle-class family is really strong. Those kids know not to talk,” she said. “At Holmes, our kids talk.”

That pressure extends to friends and neighbors who may be concerned about abuse but unwilling to risk the hassle of reporting – or of being wrong, said Lambert-Eckel.

“In upper-income families and the cul-de-sac neighborhoods, it’s like, ‘Close the window, it’s none of our business,’ ” she said.

Even worse, of every 100 Washington children exposed to chronic violence, only 25 are ever referred for intervention or care. Of those 25 kids, half are screened out because they don’t match the legal criteria for abuse. Of those that remain, fewer than four typically are found to be substantiated victims of abuse, Harrington said.

What happens to the rest?

The prognosis is not good, said Harrington. Child victims of trauma are far more likely to have trouble in school, in work, in relationships, in life. They’re more likely to perpetuate violence in their own families – and to pass the problem on to succeeding generations.

“Those kids are completely invisible to everyone,” Harrington said.

The best solution appears to lie in shifting public attitudes about abuse to emphasize shared community responsibility, advocates said: Instead of focusing on the failings of a single abusive parent, communities should focus on ways to improve the support networks that bolster all families.

Exactly how to do that remains unclear, even after decades of study, said Sharp, of the Prevent Child Abuse America agency. “The work of the last 25 or 30 years had led us to a dead end in terms of community engagement,” she said.

But they’re still trying. The latest effort, including the philosophy adopted by Spokane County agencies, focuses less on the horrific results of child abuse and more on the ways the community can come together to prevent it.

“Instead of starting from the point of despair, we’re starting from the point of optimistic hopefulness about what kids need,” Sharp said.