And now, the big picture

HOLLYWOOD — On an old studio lot outside London, a production crew began work on the movie “Sahara” in November 2003 by staging the crash of a vintage airplane.

But when the film opened in theaters in April 2005, the sequence had been deleted. “In the context of the movie, it didn’t work,” said director Breck Eisner.

The cost of the 46-second clip: more than $2 million.

This kind of spending, according to accounting records, helped turn “Sahara” into one of the biggest financial flops in Hollywood history.

The documents, obtained by the Los Angeles Times, provide a rare, behind-the-curtain peek at the thousands of expenditures that drain the budget of a major motion picture. The line items cover such things as “local bribes” within the Kingdom of Morocco and the salaries and “star perks” paid to Matthew McConaughey and Penelope Cruz.

Movie budgets are one of the last remaining secrets in the entertainment business, typically known to only high-level executives, senior producers and accountants.

“The studios guard that information very, very carefully,” said Phil Hacker, a senior partner in a Los Angeles accounting company that audits motion pictures. “It is a gossip industry. Everyone wants to know what everyone else is getting paid.”

The records offer insights into the economics of modern-day moviemaking and industry practices that seldom are disclosed. Some examples:

“ “Sahara,” an action-adventure based on the bestselling novel by Clive Cussler, has lost about $105 million to date, according to a finance executive assigned to the movie. But records show the film losing $78.3 million based on Hollywood accounting methods that count projected revenue ($202.9 million in this case) over a 10-year period.

“ About 1,000 cast and crew members worked on “Sahara.” The highest-paid was McConaughey, who received an $8-million fee, or $615,385 for each week of filming, not including bonuses and other compensation. Cruz earned $1.6 million. Rainn Wilson, who since has raised his profile through roles in “Six Feet Under” and “The Office,” was paid $45,000 for 10 weeks of work.

“ “Courtesy payments,” “gratuities” and “local bribes” totaling $237,386 were passed out on locations in Morocco to expedite filming. A $40,688 payment to stop a river improvement project and $23,250 for “Political/Mayoral support” may have run afoul of U.S. law, experts say.

“ Ten screenwriters were paid $3.8 million in fees and bonuses — highlighting the increasingly common practice of hiring and firing numerous writers on big-budget features. David S. Ward, who won an Academy Award for “The Sting,” received $500,000.

“ The production company owned by Denver billionaire Philip Anschutz got $20.4 million in government incentives to film part of “Sahara” in Europe.

Unlike most financial failures, “Sahara” performed reasonably well, ranking No. 1 after its opening weekend and generating $122 million in gross box-office sales. But the movie was saddled with exorbitant costs, including a $160-million production and $81.1 million in distribution expenses.

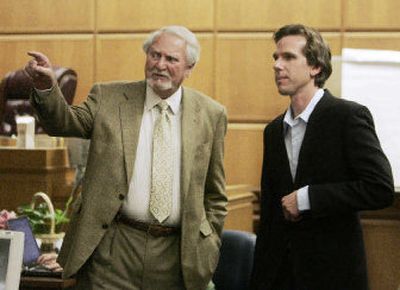

The financial documents obtained by the Times were submitted as “confidential” exhibits in an ongoing Los Angeles jury trial. Cussler initially sued, claiming that Anschutz’s producers reneged on his $10-million contract by failing to honor his right to approve the script. Anschutz countersued, alleging that Cussler exaggerated sales of “Sahara” and other Dirk Pitt adventure books and that he refused to promote the film, hurting attendance. Both sides seek millions of dollars in damages.

“I’m floored that these documents could have been provided by someone, despite the fact that there is a clear agreement within the litigation ensuring that they are confidential,” said Marvin Putnam, an Anschutz attorney. “They have been provided in clear breach of that agreement.”

The records consist of a 151-page final budget, a profit-and-loss statement, a distribution agreement with Paramount Pictures and a six-year analysis of financial transactions.

Although portions of the movie were shot in Britain and Spain, most of the filming was done in Morocco, a country in North Africa that has become a popular site for U.S. filmmakers. “Babel,” “Syriana,” “Black Hawk Down” and “Kingdom of Heaven” all have benefited from Morocco’s welcoming environment, favorable exchange rate and cheap labor.

In one impoverished village, a “Sahara” crew acquired household items at a bargain price. “We actually bought all the dressings from this person’s house at a very inflated rate, which was probably about a dollar,” Eisner said on the “Sahara” DVD.

Producers had little reason to worry about red tape or paperwork because in Morocco a single permit provides access to the entire kingdom.

Cold cash came in handy. According to Account No. 3,600 of the “Sahara” budget, 16 “gratuity” or “courtesy” payments were made throughout Morocco. Six of the expenditures were “local bribes” in the amount of 65,000 dirham, or $7,559.

Experts in Hollywood accounting could not recall ever seeing a line item in a movie budget described as a bribe.

“It’s a bad choice of words in a document, but it’s a perfectly normal and cost-efficient way of getting a film made in a place like Morocco,” said David A. Davis of FMV Opinions Inc., a Los Angeles financial advisory company.

The final budget shows that “local bribes” were handed out in remote locations such as Ouirgane in the Atlas Mountains, Merzouga and Rissani. One payment was made to expedite the removal of palm trees from an old French fort called Ouled Zahra, said a person close to the production who requested anonymity.

Other items include $23,250 for “Political/Mayoral support” in Erfoud and $40,688 “to halt river improvement project” in Azemmour. The latter payment was made to delay construction of a sewage system that would have interrupted filming.

Putnam, Anschutz’s lawyer, said the “local bribes” reflected line items that were budgeted but not actually spent. He said the payments on location in Morocco were reviewed after “Sahara” executives were contacted by the Times. “The review of all of the ledgers failed to show a single expenditure that wasn’t completely legitimate,” Putnam said.