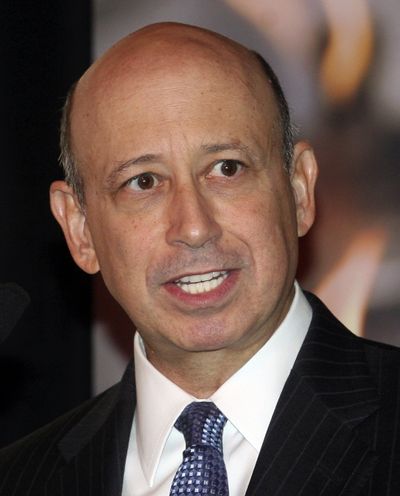

Goldman Sachs chief offers plan to restrict pay

Move may be effort to head off Congress limits

NEW YORK – The campaign to clamp down on executive pay is getting an assist from an unusual source: the head of Wall Street’s most powerful investment bank.

Lloyd Blankfein, chief executive of Goldman Sachs Group, said Tuesday that the financial industry needs a “renewal of common sense” and pay standards to “discourage selfish behavior, including excessive risk-taking.”

Blankfein said that most compensation should be in stock rather than cash, employees should be required to hold their shares for longer periods and companies should “claw back” previously paid bonuses if employee risk-taking leads to losses.

The proposals would represent a notable shift in Wall Street compensation practices, primarily by binding employee pay to the longer-term financial health of their companies.

But with Congress preparing its own crackdown on compensation, some analysts think Blankfein may be seeking to blunt an even tougher assault.

“Companies want to control these issues before legislation does it for you,” said Alexander Cwirko-Godycki, research manager for compensation information business Equilar Inc. “This is somewhat analogous to the movie industry, which created their own rating system before someone else did it for them.”

To a degree, executive pay already is reflecting the harsher financial environment. Compensation for chief executives of companies in blue-chip Standard & Poor’s 500 index fell 6.8 percent last year from the previous year, according to a study released by Equilar Tuesday.

That was the biggest drop since a 9.9 percent decline in 2002. Median pay at financial companies plunged the most – 38.3 percent – to $6.5 million, mainly because fewer than half the companies paid bonuses, Cwirko-Godycki said.

Public fury over Wall Street compensation boiled over last month after it was revealed that American International Group Inc. was paying $165 million in bonuses to employees in the unit that generated such severe losses that AIG needed a series of government bailouts, which now total $182.5 billion in commitments.

Critics say the current financial crisis was spurred by compensation structures that encouraged employees to boost short-term revenue and profits in pursuit of massive bonuses. Thus, loan officers wrote subprime mortgages that later defaulted and traders loaded up on risky positions that cost their companies billions of dollars, critics said.

Blankfein, speaking at the Council of Institutional Investors meeting in Washington, D.C., said that “compensation should take into account strict adherence to a firm’s management and controls, especially with respect to a person’s judgment and exercising that judgment in terms of risk in all of its forms.”

Jeanne Branthover, head of the financial services practice at Boyden Global Executive Search in New York, said the comments could be viewed as mea culpa.

“It’s their effort to say, ‘Looking back, we didn’t do the right things but we want you to know that looking forward, there will be change and we’re listening to the public,’ ” she said. “There is no doubt that senior management, the leaders of Wall Street, understand there must be a change in the compensation structure and the mind set of the employees receiving bonuses.”

Blankfein only reiterated the industry’s long-held position that companies need the flexibility to pay incentives to attract the best talent.

Blankfein himself earned $43 million last year in total compensation.