Nobel given days after death

Cell scientist honored; panel unaware he died

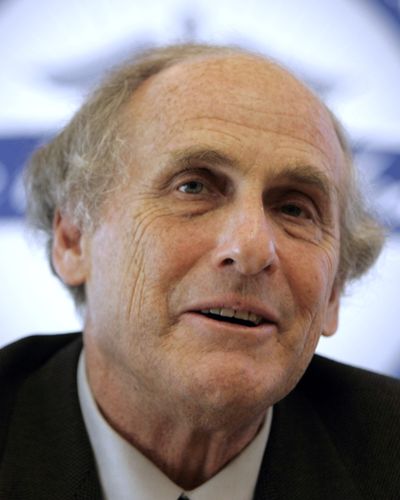

NEW YORK – Ralph Steinman, a pioneer in understanding how cells fight disease, tried to help his own immune system thwart his pancreatic cancer.

Steinman survived until Friday. Three days later, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine.

The Nobel committee, unaware of his death, announced the award Monday in Stockholm. Steinman’s employer, Rockefeller University in New York, learned of his death after the Nobel announcement.

Steinman’s wife, Claudia, said the family had planned to disclose his death Monday – only to discover an email to his cellphone from the Nobel committee.

Experts disagree whether Steinman’s research helped him live for 4 1/2 years after he was diagnosed. A colleague in his lab thinks it did. The odds of making it even a year with his type of cancer are less than 5 percent.

Nobel officials said they believed it was the first time that a laureate had died before the announcement without the committee’s knowledge.

“It is incredibly sad news,” said Nobel Foundation chairman Lars Heikensten. “We can only regret that he didn’t have the chance to receive the news he had won the Nobel Prize. Our thoughts are now with his family.”

Since 1974, the Nobel statutes don’t allow posthumous awards unless a laureate dies after the announcement but before the Dec. 10 award ceremony. That happened in 1996 when economics winner William Vickrey died a few days after the announcement.

However, the committee said Monday that Steinman’s award would stand and that his survivors would receive his share of the $1.5 million prize.

The Canadian-born Steinman, 68, was awarded the prize along with American Bruce Beutler and French scientist Jules Hoffmann. They were honored for discoveries about the body’s disease-fighting immune system.

Steinman discovered so-called dendritic cells in 1973. These cells regulate the activity of other cells – Steinman called them the conductor of the immune system.

“When he got sick, he realized he needed to call upon these cells to induce a strong enough immune response to fight his tumor, and that is what he did,” said Dr. Sarah Schlesinger, clinical director for his lab.

Steinman tried eight to 10 experimental therapies approved by the federal government, focusing in various ways on revving up his immune system to fight his cancer, she said.

In one approach, samples of Steinman’s own dendritic cells were loaded with protein markers from his tumor, and then reinjected into his body. The idea was that this would “teach his immune system how to respond to that tumor,” said Rockefeller colleague Dr. Michel Nussenzweig.

Steinman was the only patient, with no control group – other patients with the same cancer for comparison, a scientific must for convincing evidence. “It’s not the kind of experiment Ralph would have liked to have done.”

Rockefeller University said “his life was extended” using the therapy of his own design. Schlesinger believes that, pointing to the poor survival odds for his tumor and his good quality of life during his treatment. Noting that he also got chemotherapy, she said, “I think it all worked together.”

But Dr. Alan Venook, a pancreatic cancer specialist at the University of California, San Francisco, cautioned against drawing conclusions about the impact of the treatments.

He said surviving four years with pancreatic cancer “is a long time,” but not out of the question, depending on the type and how advanced it was when it was found.

“It’s a disservice to the field for anyone to say that his immune therapy prolonged his life,” Venook added.

Hoffmann, 70, headed a research laboratory in Strasbourg, France, between 1974 and 2009 and served as president of the French National Academy of Sciences in 2007-’08.

Beutler, 53, holds dual appointments at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and as professor of genetics and immunology at the Scripps Research Institute in San Diego. He will become a full-time faculty member at UT Southwestern on Dec. 1.

Beutler and Hoffmann were cited for their discoveries in the 1990s of receptor proteins that can recognize bacteria and other microorganisms as they enter the body, and activate the first line of defense in the immune system, known as innate immunity.

The work of the three men has enabled the development of improved vaccines against infectious diseases, and in the long term could yield better treatments of cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, Type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis and chronic inflammatory diseases, Nobel committee members said.

The work could also help efforts to make the immune system fight cancer, the committee said.

The medicine award kicked off a week of prize announcements, with the physics prize today, chemistry on Wednesday, literature on Thursday and the Nobel Peace Prize on Friday. The winners of the economics award will be announced Monday.