Report alleges Penn State cover-up

Investigator: Top officials showed ‘callous disregard’ for Sandusky’s victims

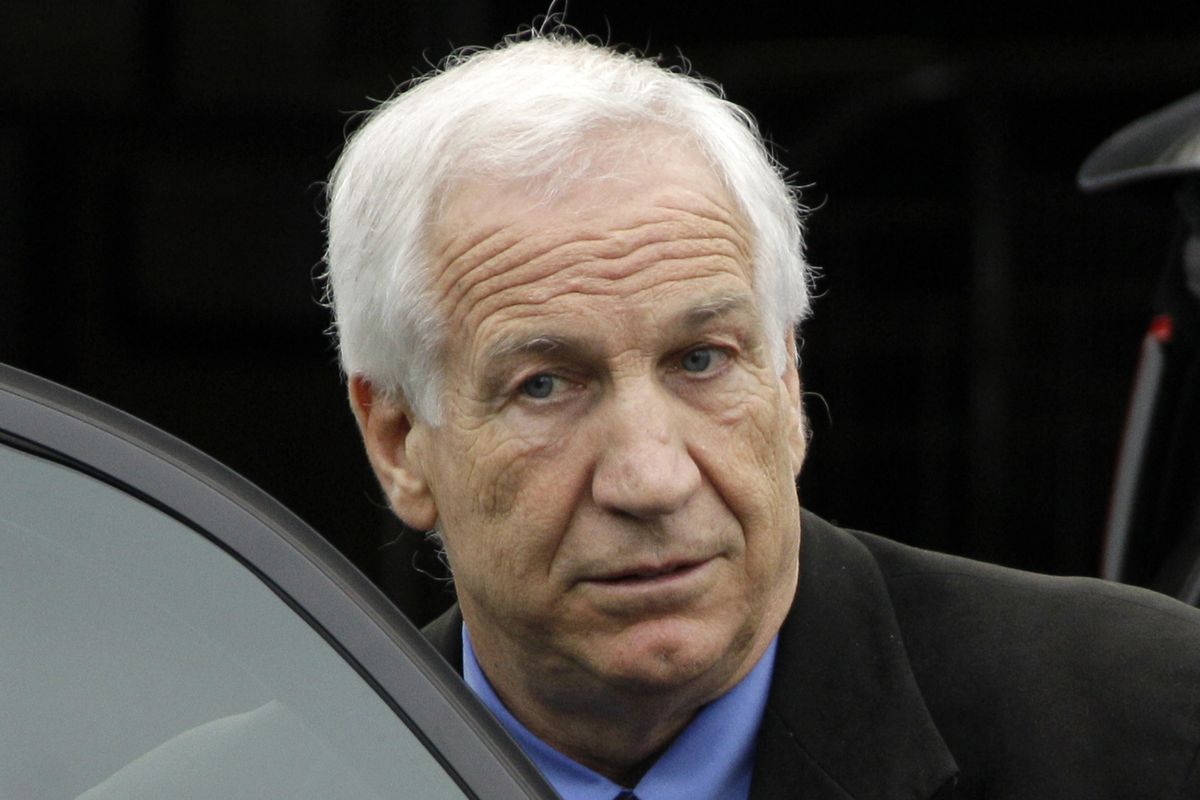

PHILADELPHIA – Deceased former football coach Joe Paterno, former Pennsylvania State University President Graham B. Spanier and other top administrators conspired for more than a decade to keep quiet sex-abuse allegations against Jerry Sandusky, according to the findings of an internal investigation released Thursday.

Fearing bad publicity, the head football coach and the president, along with athletic director Tim Curley and Gary Schultz, a former vice president in charge of campus police, “repeatedly concealed critical facts” and exhibited a “callous disregard for child victims,” enabling the former assistant football coach to prey on boys for years, said Louis Freeh, a former FBI director commissioned last year to lead the investigation.

“Our most saddening and sobering finding is the total disregard for the safety and welfare of Sandusky’s child victims by the most senior leaders at Penn State,” Freeh said at a news conference Thursday in Philadelphia. “The most powerful men at Penn State failed to take any steps for 14 years to protect children whom Sandusky victimized.”

The report is damning in the evidence it marshaled – emails, interviews, long-hidden notes – to show repeated and extensive efforts by Spanier, Curley and Schultz to rationalize, conceal and ultimately dissemble when confronted first by accusations against Sandusky and later by requests from authorities, including trustees, to explain their own roles.

The report specifically shows Spanier stonewalling and misdirecting trustees when pressed for more information about an ongoing grand jury investigation into Sandusky, who was convicted last month of sexually molesting 10 boys over the last 14 years.

Freeh’s investigation also found that Penn State had a culture of deference to figures such as Paterno and Spanier even as those leaders failed in their roles.

“The board’s overconfidence in Spanier’s abilities and its failure to conduct oversight and responsible inquiry of Spanier and senior university officials hindered (its) ability to deal properly with the most profound crisis ever confronted by the university,” the document says.

At a news conference Thursday in Scranton, a cadre of grim-faced trustees – including Ken Frazier, chair of Penn State’s special investigations task force – vowed to chart a new course based on the report’s findings and recommendations, which are likely to loom large in an expected torrent of civil lawsuits and ongoing investigations.

“Let me be absolutely clear,” Frazier said. “An event like this can never happen again. … We are accountable for what happened here.”

In a statement Thursday, Paterno’s family said the now-deceased coach “mistakenly” believed others would investigate the allegations.

“The idea that any sane, responsible adult would knowingly cover up for a child predator is impossible to accept,” the statement said. “The far more realistic conclusion is that many people didn’t fully understand what was happening and underestimated or misinterpreted events.”

Spanier’s lawyers described the conclusion of a cover-up as “simply not supported by the facts.” Attorneys for Curley and Schultz called the investigation “lopsided” and said it left “the majority of the story untold.”

Curley and Schultz await trial on charges they failed to report allegations against Sandusky to authorities and later lied about it to a grand jury.

Spanier has not been charged with a crime. Sources close to an ongoing grand jury investigation have said he has recently become a potential target.

Freeh declined to speak Thursday on whether Spanier should join Curley and Schultz in facing criminal charges.

Some of the report’s most damning findings came in the form of emails and handwritten communications that directly contradict previous testimony from Paterno, Spanier, Curley and Schultz before the grand jury that investigated Sandusky.

The men testified last year that they did not know or were only vaguely aware that campus police had investigated a report in 1998 from a mother upset that Sandusky had showered with her son.

Though no criminal charges were filed in that case, Curley noted in one 1998 email cited in the report: “Coach is anxious to know where (the investigation) stands.”

All four were repeatedly briefed on the probe, according to Freeh’s report.

In another set of notes taken from an early meeting on the case, Schultz wrote to himself: “Is this opening a Pandora’s box?”

Their behavior in light of subsequent allegations suggests Schultz and the others were eager to keep that box closed.

In 2001, graduate assistant Mike McQueary alerted Paterno, Curley and Schultz that he had walked in on Sandusky engaging in sexual activity with a 10-year-old boy in a locker-room shower.

Paterno and the administrators testified last year that they never alerted authorities because McQueary failed to make clear to them the severity of what he saw.

Emails cited in Freeh’s report Thursday suggest they knew enough to be concerned.

Immediately after hearing of McQueary’s allegations – but before speaking to McQueary – Schultz drafted a plan, along with Curley and Spanier, to report Sandusky to state child-welfare investigators. Only after “talking it over with Joe” did Curley propose an alternative in an email dated Feb. 27, 2001: Confront Sandusky, ban him from bringing children on campus, and only report him should he deny having a problem.

Spanier agreed, writing that “the only downside for us is if the message isn’t (heard) and acted upon, and then we become vulnerable for not having reported it.”

While the administrators struggled with how to deal with Sandusky, “there is no indication that Spanier, Schultz, Paterno, Curley or any other leader at Penn State made any effort to determine the identity of the child in the shower or whether the child had been harmed,” Thursday’s report reads.

But as much blame as Freeh’s report heaps on administrators, it also takes aim at the culture at Penn State that gave so much unchallenged power to Paterno and, by extension, Spanier.

In one interview, a university janitor explained why he never reported an incident in 2000 in which a co-worker saw Sandusky performing oral sex on an adolescent boy. “It would have been like going against the president of the United States, in my eyes,” he said. “I know Paterno has so much power, if he wanted to get rid of someone, I would have been gone.”

Trustees told Freeh that despite their chartered role as university overseers, they often felt as if their meetings were “scripted” by Spanier and they were there to “rubber stamp” his decisions.

Even after news reports first emerged about the grand jury investigation into Sandusky, Spanier was slow to brief trustees on the university’s potential liability. Many of them learned of the arrests of Sandusky, Curley and Schultz in November only after reading about them in the newspaper, Freeh said.

The report also exposes failings within Penn State’s oversight system, including a scathing assessment of the university’s compliance with the federal Clery Act. The law requires the reporting of certain crimes on campus, including sexual assaults, even if criminal charges are never filed.

Neither the 1998 nor 2001 allegations against Sandusky were reported under the act, Freeh noted. Between 2007 and 2011, only one Clery report was made for the entire campus.

“The Penn State board failed to exercise its oversight functions,” Freeh’s report states. “Because the board did not demand regular reporting of these risks, Spanier and other senior university officials did not bring up the Sandusky investigations.”

Lawyer Thomas Kline, who represents one of Sandusky’s victims, described the Freeh report as a “road map and a guideline” for civil suits against the university.

“The report clearly concludes there was a colossal and monumental failure by Penn State at the highest level,” he said.