100 years ago this week the United States entered World War I, a conflict that would claim the lives of 200 from the Spokane area

By April 6, 1917, the day the U.S. formally entered World War I, Spokane residents already had been fighting with Germans for three years. But not on battlefields. They were brawling in Spokane’s motion-picture houses and saloons.

Tensions ran so high in Spokane after the war broke out in Europe in 1914 that the mayor proposed an edict forbidding all newsreel war documentaries. The mayor said that scenes from the war had caused outbursts that were “hard to control” between “men of foreign birth” (meaning, probably, Germans and Austrians) and the rest of the audience.

The mayor later withdrew that proposal. Yet it illustrates the fraught atmosphere that existed in Spokane and the rest of the United States during the three years that the country stayed neutral in the war. When Americans finally entered the war, the tension ratcheted even higher. The terms “enemy alien” and “seditionist” became commonplace.

The lead-up

The first thing to know about World War I was that, at the time, nobody called it World War I. That name would not be used until a second world war made it necessary. It was simply the European War or the Great War, and later, after the U.S. entered, the World War. Under any name, it had dominated the news in Spokane since 1914.

Residents were clearly divided. In 1915, the Lusitania, a passenger liner, was sunk by German torpedoes with great loss of life. A German shoemaker named Elbert Abitz was sitting in a Spokane saloon, “rejoicing over” the sinking. This enraged L.T. Jacobs, described as a “colored Navy veteran,” who whacked Abitz with a cane and started a brawl. Both were arrested, but by this time, Spokane opinion was firmly on Jacobs’ side. The sinking of the Lusitania had shocked most Americans and marked a hard turn of U.S. public opinion against Germany.

Many other torpedo attacks followed. The torpedo war came home to Spokane in May 1917 when Mary E. Hoy and her daughter Elizabeth Hoy, lately of Spokane, perished when a German submarine torpedoed the liner Laconia in the Atlantic Ocean. The Spokesman-Review’s editorial page wrote that “the assassin of the seas has leapt upon its victim from behind and struck the coward’s blow.”

Spokane’s newspapers were now full of articles about “preparedness,” a term which meant roughly the opposite of “pacifism.” When war with Germany became inevitable, the term “patriotism” replaced “preparedness.” On March 25, 1917, a patriotic rally was held at the Spokane Armory. About 5,000 “patriots” were jammed in. Another 3,000 were gathered in an overflow area on the street. Another 4,000 couldn’t even get near the place. Those inside unanimously adopted a resolution that concluded, “In this hour of crisis, we are Americans without division.”

The declaration

President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war on April 2, and formally signed it on April 6. By this time, most Americans supported the move.

Yet Americans were not entirely without division. U.S. Representative C.C. Dill, from Spokane’s district was one of the 50 representatives who voted against the war resolution (compared to 370 in favor). Back in Spokane, a newly formed group called the Spokane Patriotic League gathered in a “huge throng” and angrily repudiated Dill. When a few people stood up in defense of Dill, people shouted, “Sit down, sit down, down, you traitors!”

“Thus it was that the citizens of Spokane repudiated their congressman in the greatest national crisis since the civil war,” said a front-page story in The Spokesman-Review.

Enlistment and conscription

Young men in Spokane already had been enlisting in droves, but after the declaration of war, the pace picked up dramatically.

It had to. The War Department issued a directive on April 7, 1917, calling for Spokane to furnish 500 men immediately for Uncle Sam’s army, followed by another 500 men by summer, and another 500 men within the year, for a total of 1,500. The rest of the Fifth Congressional District in Eastern Washington was required to supply the same number, bringing the Eastern Washington total to 3,000. The overall goal was to create a force of 1 million soldiers.

However, by June 1917, General John J. Pershing, the commander of the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe, shocked American officials by saying he needed 3 million American troops. There was only one way to get that many soldiers: conscription. A draft registration was instituted for all men between ages 21 and 30 (later broadened to ages 18 to 45).

The stream of recruits in Spokane became a flood. By July 1918, Spokane’s army recruiting district had enlisted more than 11,000 men. Thousands more joined the U.S. Navy.

Over There!

Many of those 11,000-plus would end up in Europe. The 189 soldiers of Battery F, 146th Field Artillery, “composed exclusively of Spokane and Inland Empire men” saw more than their share of combat. Their story, as related in a 1926 article in The Spokesman-Review by battery member R.L. Richardson, serves as a particularly vivid example of a Spokane soldier’s experience.

The battery was organized by Spokane volunteers in July 1917. They were mustered into the army at Fort Walla Walla in September 1917 and then sent to a succession of training camps – Camp Greene in North Carolina, Camp Mills on Long Island, and Camp Merritt in New Jersey. On December 24, 1917, the men were loaded onto a ship and sent – “as a Christmas present,” in Richardson’s wry phrase – to Liverpool.

On January 11, 1918, the battery arrived in France. In Bordeaux, they spent months learning to accurately fire “the new and powerful 155-mm grand power filloux, a marvelous and mobile mechanism which fired 100-pound projectiles over 10 miles and whose accuracy was so great to give it the name of long range sniper.”

On July 7, 1918, Battery F finally arrived at the front, to an area called the Marne, already a bloody and notorious battleground. From July 15-17, 1918, the guns of Battery F “thundered continuously … and played no small part in repulsing the Boche (Germans) in his last big effort,” wrote Richardson.

On July 18, French and American troops pursued the retreating Germans. “For the artillery, it was a matter of standing by the guns day and night until our troops had advanced so far that further firing was dangerous to them,” wrote Richardson. “ During this advance, nearly 40 miles of shell-torn road was traversed by the guns, and the number of emplacements for each gun ran from 10 to 18, which showed how fast Fritz (German soldiers) could run.”

Battery F had earned a welcome rest for a few days, but then it was off to another battle in France on the St. Milhiel salient. Then in September 1918 the battery arrived at “the devilish affair called the Meuse-Argonne offensive.” On Sept. 26, Battery F and other American guns opened fire and “hell broke loose for the Germans.”

Yet it was also the beginning of 47 straight days of hell for Battery F. Here’s how Richardson described it: “Nights of firing and days of moving; tragedies written into the heart of all of them, with no comedy; work, work, work, with no let-up and no relief; hours of straining to get gun wheels back on doubtful roads, only to have them slip again; more meals postponed than eaten; the sleep of exhaustion in soggy blankets; men balanced two-deep in a friendly truck and glad to be there. If material faltered, cast aside. If men faltered – but none did.”

Then began a series of misfortunes “that dogged the footsteps of Battery F until the end of hostilities.” The first – and worst – arrived in the form of a German shell that scored a direct hit on a pile of gas shells, stacked next to one of the Battery F guns. These “sprayed the entire crew with deadly phosgene gas and sent nine of them to hospital.” Corporal Arthur Lewis died immediately.

Battery F moved on to Nantillois, “by far the hottest place” the battery ever fought. German shells scored two direct hits on a Battery F gun, instantly killing Walter L. Smith of Elk. “Many others had close calls with death at Nantillois and all wished we were safe at home,” wrote Richardson.

Battery F was still firing on machine gun nests on Nov., 1918, when word arrived: The armistice was signed and the war was over. But the work was not over for Battery F, which was assigned to the army of occupation. The men spent Christmas Day in Bassenheim, a “German town that looked as though it had stepped from a Christmas decoration.” In May 1919, Battery F finally came home to not one, but two, triumphal parades. The first was in Walla Walla, and the second was in Spokane, as “the largest crowd ever to review troops in the city, gathered to cheer and kiss those returned.”

Yet not everyone had returned. Four Battery F members had died in action and 20 were wounded or gassed.

Casualties

About 200 other Spokane-area men would never return. On June 12, 1918, Charles Burtsch (sometimes spelled Burch), 17, a Lewis and Clark High School student, was one of four soldiers who had volunteered to set up an outpost in a shell crater halfway between the American and German lines. German soldiers, according to accounts of survivors, began crawling “snake-like” toward these four members of Company I, 161st Infantry. Soon Burtsch and the other three soldiers “were surrounded by Huns.”

They dodged bullets, but were unable to dodge a German shell. Burtsch’s last words, as he lay dying were, “Tell Company I that we didn’t run from ‘em.”

He was one of at least 20 Lewis and Clark students and graduates to die in the war.

Not all of Spokane’s casualties were in the U.S. Army. A.R. “Dickie” DeLay, a native of Canada, had left his job as clerk at the Spokane branch of the Bank of Montreal to join the British air force. He was training as a pilot in Britain when he wrote a letter home describing a visit he had just made with some other Spokane boys, who were training nearby. “Sure had a good time,” he wrote. “… It was the first time I had seen a Spokesman-Review since leaving Spokane and it sure did my heart good. It brought back some of the happiest days of my life, and intensified my desire to return to the sunny city as soon as possible. I expect, in the course of a few days, and probably before you get these rambling lines, that I will experience the sensation of ‘strafing Fritz.’”

Before those “rambling lines” arrived in Spokane, DeLay was shot down and killed over German lines.

Spokane’s nurses

One 1918 headline read, “War to Drain The City of All Registered Nurses.”

The demand was insatiable for trained nurses at the front, and many Spokane nurses volunteered. By mid-1918, about 67 of Spokane’s estimated 240 nurses were serving with the army or navy.

Yet this wasn’t enough. The president of the local nurses’ association said that the war effort required the service of one out of every three nurses.

Spokane launched a drive to recruit student nurses. Dr. Anne Howard Shaw, chairman of the local women’s committee for national defense, issued this plea: “This call is to all young women who are strong, loyal and worthy of our country, to enroll as soon as possible.”

Left unsaid was this: nursing could be hazardous duty. Norene Royer, a graduate of Spokane’s Sacred Heart Hospital nursing school, died in France of pneumonia four months after enlisting.

“Slackers” and “deserters”

At home in Spokane, considerable ire was aimed at “slackers,” meaning those who refused to register for the draft. Spokane police conducted routine roundups of slackers, “idlers” and deserters. One such roundup netted 10 men, several of them described as “Austrians.” “The purpose is to get idlers on the move,” said a news story.

One man was approached in a Main Avenue restaurant by volunteers selling Liberty Loans (war bonds). The man gruffly replied that he had never bought a war bond and never would. The war bond workers contacted a police officer, who asked to see the man’s draft registration card. When he could not produce one, he was hauled to jail “as a suspected slacker.”

Another Spokane man, when asked to subscribe to the Spokane Red Cross chapter, was arrested for “uttering disloyal remarks.” He allegedly called the U.S. government “rotten.” He was found guilty in federal court for “violating the espionage act” and fined $300.

“Enemy Aliens” and “Seditionists”

At the beginning of 1918, all “German alien men” over the age of 14 were ordered to register at Spokane police headquarters. The order would later apply to women, too. Within months, the U.S. marshal in Spokane had compiled registration records on 1,000 German alien men and 552 German alien women in Eastern Washington.

If they failed to register, the consequences were drastic. One man, identified as Edwar Loesch, alias Charles Stromur, “a German and unregistered alien,” was picked up by Spokane police and taken to Fort George Wright. From there, he was to be “conducted by an armed guard to Fort Douglas, Utah, and interned for the duration of the war.” Many others also would end up at Fort Douglas.

A Spokane county sheriff summed up one popular view when he said that “any man who has come to this country, taken advantage of its resources, accumulated funds and then refused to support this country ought to be deported.”

Germans were not the only group suspected of sedition. Kathleen O’Brennan, an Irish Sinn Fein lecturer, was threatened with deportation by a Spokane city commissioner after a speech in which she assailed Great Britain, a U.S. ally.

The Wobblies (members of the radical Industrial Workers of the World) were another common target. The Wobblies were strongly anti-war because they felt it was a war of nationalism. When the Wobblies continued to agitate in 1917 for a strike of Eastern Washington agricultural workers, authorities suspected it was part of an attempt to damage the nation’s war effort.

Military authorities raided the Spokane Wobblies headquarters. They rounded up several German enemy aliens amongst the 27 men taken into custody. However, military authorities later admitted that they had found “no direct proof” that German agents had been financing the Wobblies strike plans.

Later, another 22 Wobblies were rounded up in Minnehaha Park for conspiring “to obstruct the war program,” by calling for a general strike in the region’s mines and lumber camps.

The home front and the Home Guard

On the home front, Spokane residents supported the war effort by volunteering for the Red Cross, which provided aid for soldiers and war victims. People also raised their own “war gardens” (later called victory gardens), to free up more food to be sent to Europe. Spokane industries also worked with federal authorities to maximize production of war necessities.

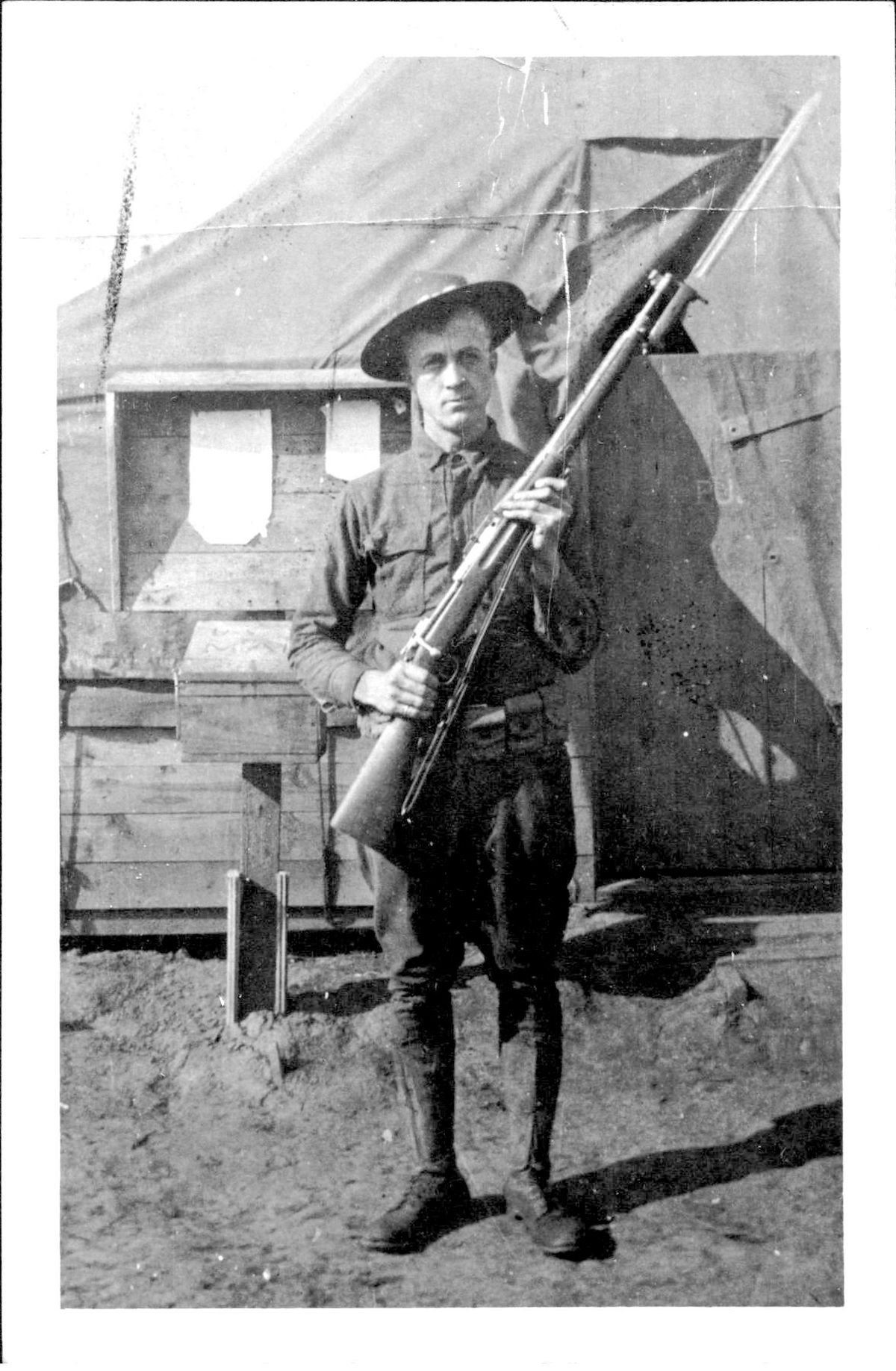

The men of the Spokane Home Guard, however, took a more direct part in the war effort. They were local “lawyers, painters, miners, electricians, barbers, clerks” who devoted their off-hours to military drilling. During one practice drill, this small army was mobilized to chase an “imaginary German scouting party” away from the upriver water pumping station on the Spokane River. Home Guard men, with rifles in hand, jumped into a fleet of passenger autos and light trucks and scooted down Mission Avenue in a mile-long procession. They successfully defended this imaginary attack, yet were never mustered for a real one.

Fort George Wright

In the early months of the war, Spokane’s Fort George Wright served as a receiving camp for local recruits. During one three-day stretch in December 1917, more than 1,100 recruits arrived. The commanding officer asked some recruits to “go back downtown” to sleep; he didn’t have enough beds for them. Most of the recruits were shipped out by rail to Camp Lewis, near Tacoma, as soon as possible.

Fort George Wright later served as a holding camp for some combat units, including the 14th Infantry, before embarking for Europe. It also was the site of a “modern automobile and tractor school” – apparently an army school for mechanics.

As the end of the war approached, Fort George Wright became, ominously, “an improvised Spanish influenza hospital.” A number of trainees in the automobile school had arrived with this dangerous strain of flu. Before long, 208 men were sick. At least seven died within a week. A call went out for all available nurses in Spokane – but only four trained nurses could be found.

This was just a foretaste of the Spanish flu epidemic that would devastate Spokane toward the end of the war.

The armistice and the memorials

“WORLD WAR ENDED” shouted The Spokesman-Review’s gigantic headline on November 11, 1918.

News of the armistice ignited “the largest, wildest most delirious celebration the city ever witnessed,” said the paper. A big bonfire burned at Main Avenue and Monroe Street. An effigy of Kaiser Wilhelm, “constantly jeered at,” swayed from a guy wire at Riverside Avenue and Howard Street.

Marching bands paraded through downtown. An endless stream of autos honked their horns. Boys and girls “did the serpentine dance” down the center of Riverside. “The spirit of the big, hilarious, good-natured, orderly crowd was summed up in the words on the kaiser’s effigy: ‘Ex-Kaiser Bill – Goodbye! To h-ll with the kaiser!’”

The next day’s paper carried this banner headline: “Armistice Terms Take From Germany All Power to Renew World War.” The delirious crowds were, mercifully, unaware of how wrong that statement would be.

A century later, Spokane has several modest memorials to those who served and died in World War I. In the entrance hallway of Lewis and Clark High School, a plaque pays honor to 20 LC students who “gave their full measure of devotion … in the Great War of Nations.” A similar plaque at North Central High School honors nine students “who answered America’s call in the war for democracy.”

The Riverside Avenue bridge over Latah Creek displays several bronze plaques declaring its official name as “the Marne Bridge.” The bridge was dedicated on Armistice Day, 1920, “to the men of Spokane who died in the Great War.”

At Spokane’s Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist, a large bronze plaque lists the names of 128 “Spokane soldiers, sailors and marines” who gave their lives during the World War. The plaque originally stood near a set of tubular chimes. The plaque proclaims that “the ringing of the cathedral chimes” is a “perpetual memorial” to these war dead.

The chimes are long gone. Yet they were replaced by chimes of an even grander variety, the 49-bell carillon in the cathedral tower. Whenever those carillon bells ring out across the South Hill, think of it as a musical homage, tolling for the Spokane souls lost in the Great War.

Note: This story was researched largely from the archives of The Spokesman-Review and Spokane Daily Chronicle, from HistoryLink.org, The Encyclopedia of Washington State History and from the extensive World War I collection of the Northwest Room of the Spokane Public Library.