Biographer Gary Giddins shines light on Bing Crosby’s ‘War Years’

At this point in his career, writer and educator Gary Giddins practically knows more about Bing Crosby than Bing Crosby knew about Bing Crosby.

After decades of research into the life and career of the famed singer and actor (and former Spokane resident), Giddins is releasing his second of three Crosby biographies.

The first, “Bing Crosby: Pocketful of Dreams - The Early Years 1903-1940,” was released in 2001.

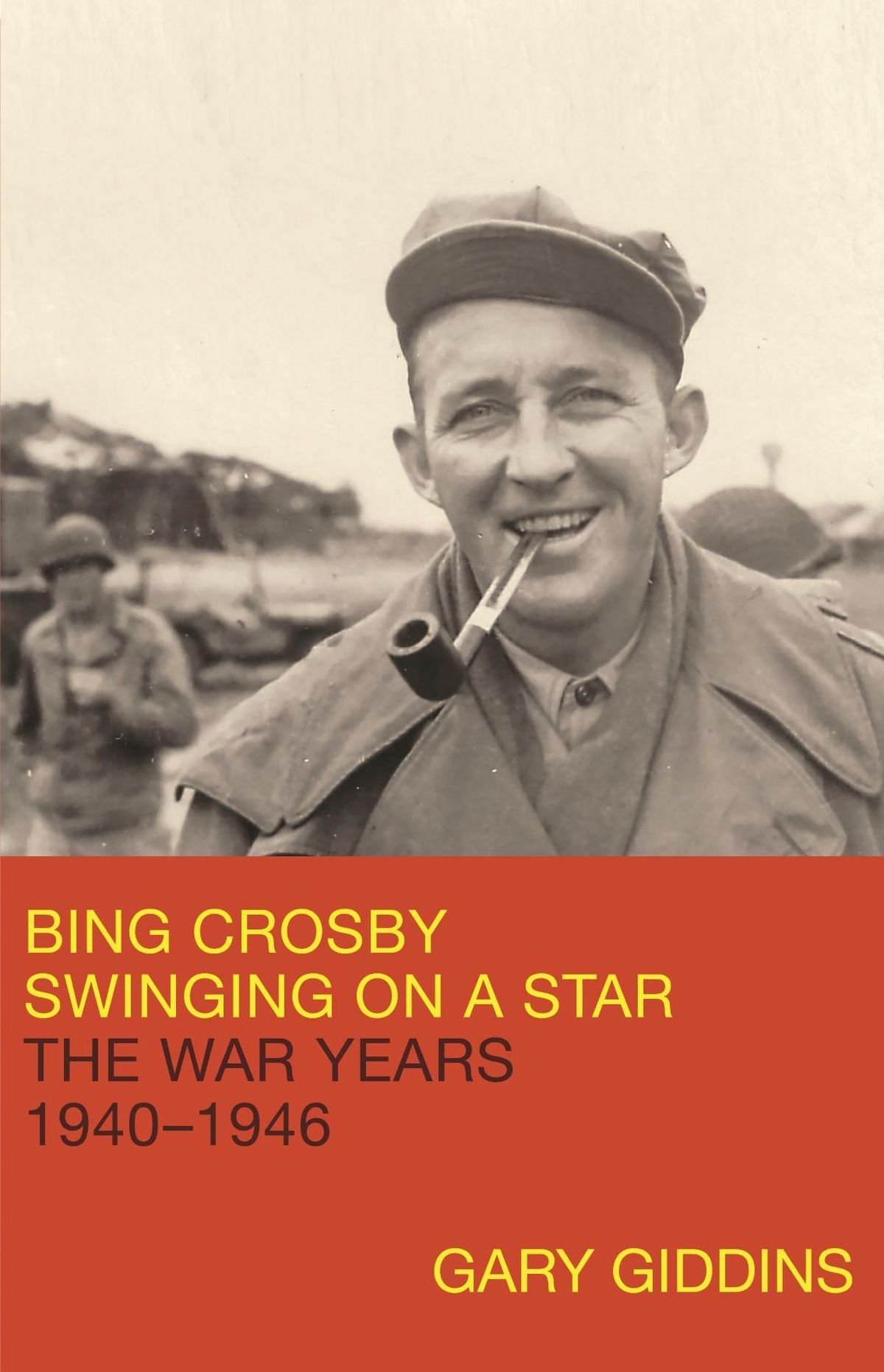

The second, “Bing Crosby: Swinging On a Star - The War Years 1940-1946,” will hit shelves Tuesday.

In celebration of the book’s release, Giddins will return to Crosby’s hometown Thursday for two events, one at the performer’s namesake theater at 2 p.m. and one at Gonzaga University, which Crosby attended for three years, at 7 p.m.

It didn’t take much for Giddins to become a fan of Crosby.

He remembers listening to a Folkways anthology of jazz and hearing Crosby singing on Paul Whiteman’s “Louisiana.”

“That really knocked me out,” he said in a recent interview.

He then heard a couple vocals from Crosby and the Rhythm Boys (the trio of Crosby, Harry Barris and Al Rinker) on a Bix Beiderbecke album, and soon after had a two-record collection of some of Crosby’s recordings from the early 1930s on repeat.

But, Giddins admits, that was pretty much all the Crosby he listened to until RCA put out a record that featured Crosby’s 1957 album “Bing with a Beat.”

Then, he was all in.

When Crosby played the Uris Theater (now called the Gershwin Theatre) in 1976, Giddins was there, writing a story for Village Voice.

He even got to spend a few minutes with Crosby before the show.

“I was just bowled over by his professionalism, how cool he was,” Giddins said. “Everybody else was yelling about the rehearsal. ‘You should be on this mark. You should be on that mark,’ and so forth and Bing, he let it just breeze right over him. He was really quite extraordinary.”

Years later, Giddins began work on “Pocketful of Dreams,” which chronicled Crosby’s upbringing in Spokane and the early years of his career.

“Gary Giddins has performed a great service in tracking Crosby’s life and career so scrupulously,” Robert Gottlieb wrote in a review for the New York Times. “He’s not only superb on the music, but he has lovingly considered the films of the 30s… a masterly performance.”

Seventeen years and several books separate “Pocketful of Dreams” and “Swinging on a Star” but Giddins never stopped doing research on Crosby.

Just months after “Pocketful of Dreams” was released, Giddins was back in Los Angeles, visiting the Margaret Herrick Library and, unexpectedly, the home of Crosby’s second wife, Kathryn.

Kathryn hadn’t been cooperative when Giddins reached out while working on “Pocketful of Dreams,” but after her son Harry persuaded her to read the book, she invited Giddins to look through Crosby’s files, letters, contracts and journals.

That meeting ended up changing Giddins’ plan for “Swinging on a Star” completely.

What was originally going to be the second of two biographies, chronicling the latter half of Crosby’s life, turned into a book about his experience during World War II, inspired by letters Crosby received from soldiers and the parents, siblings and friends of soldiers who died in the war, as well as the journal Crosby kept during those years.

“To be able to write about the homefront from the view of Crosby seemed like an irresistible project, and also it’s his most important years as an artist in many respects,” Giddins said.

Crosby’s journal especially gave Giddins a lot of insight into his life during the war, which, according to Giddins, was much more extensive than many thought because Crosby did a lot of work that the press didn’t see.

Traveling an estimated 50,000 miles around the country and overseas, sometimes with his children and others with just a pianist or guitarist as accompaniment, Crosby performed for countless soldiers.

The humble Crosby didn’t boast about this work, even making a joke about the Hollywood Victory Caravan in his memoir “Call Me Lucky.”

“I think he hated when people slapped themselves on the back over doing this,” Giddins said. “He thought it was his duty.”

But he shared the personal significance of his work with those close to him.

“If you look at interviews at that time and personal letters, he said ‘This is the most important thing I’ve ever done in my life,’ ” Giddins said.

Soldiers were as appreciative of his work as he was of theirs, naming him the person who had done the most to boost morale during the war, over then-President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Gens. Eisenhower and MacArthur and fellow entertainer Bob Hope, in a poll by Yank, the Army Weekly.

“Number one,” Giddins said. “That says a lot.”

Having access to Crosby’s original manuscripts for “Call Me Lucky,” as well as interviewing Crosby’s sons Gary and Phillip, also allowed Giddins to rewrite some of what Gary wrote in his memoir “Going My Own Way” about Crosby’s use of corporal punishment.

Giddins found out that Dixie Lee, Crosby’s first wife and Gary’s mother, was behind the punishments more often than Crosby.

“Bing speaks more about his parenting and his concern about the kids, but he wasn’t a mean or uninterested father,” Giddins said of the original manuscripts. “The problem was he was too bloody interested, too much discipline, too much thinking he could force them to be very different from when he was a kid. He didn’t want his sons being like he had been.”

“Swinging on a Star” also features an in-depth look at “Going My Way,” the film for which Crosby won the Academy Award for Best Actor, and director Leo McCarey.

“One of the things nobody talks about anymore is that he had a tremendous influence on young men going into seminaries and taking their vows, wanting to be Father O’Malley,” Giddins said. “I compare it in the book with the way a lot of people during the civil rights era saw ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ and decided to study law.”

Crosby died in Spain in 1977 at the age of 74, which means there are 30 years of Crosby’s life Giddins has yet to write about.

He’s done the research but doesn’t have a contract for the third volume. Giddins thinks getting a contract depends on how well “Swinging on a Star” is received.

But it’s hard not to like Crosby, the man behind “White Christmas,” Father O’Malley and the “Road to …” series.

“He unified the country with his art …,” Giddens said. “High school kids loved him and their parents loved him and their grandparents loved him. There was no gender distinction. … There was no bias in terms of ethnicity …

“I can’t think of anybody in my lifetime of whom you could say that everybody was into him,” Giddins said.