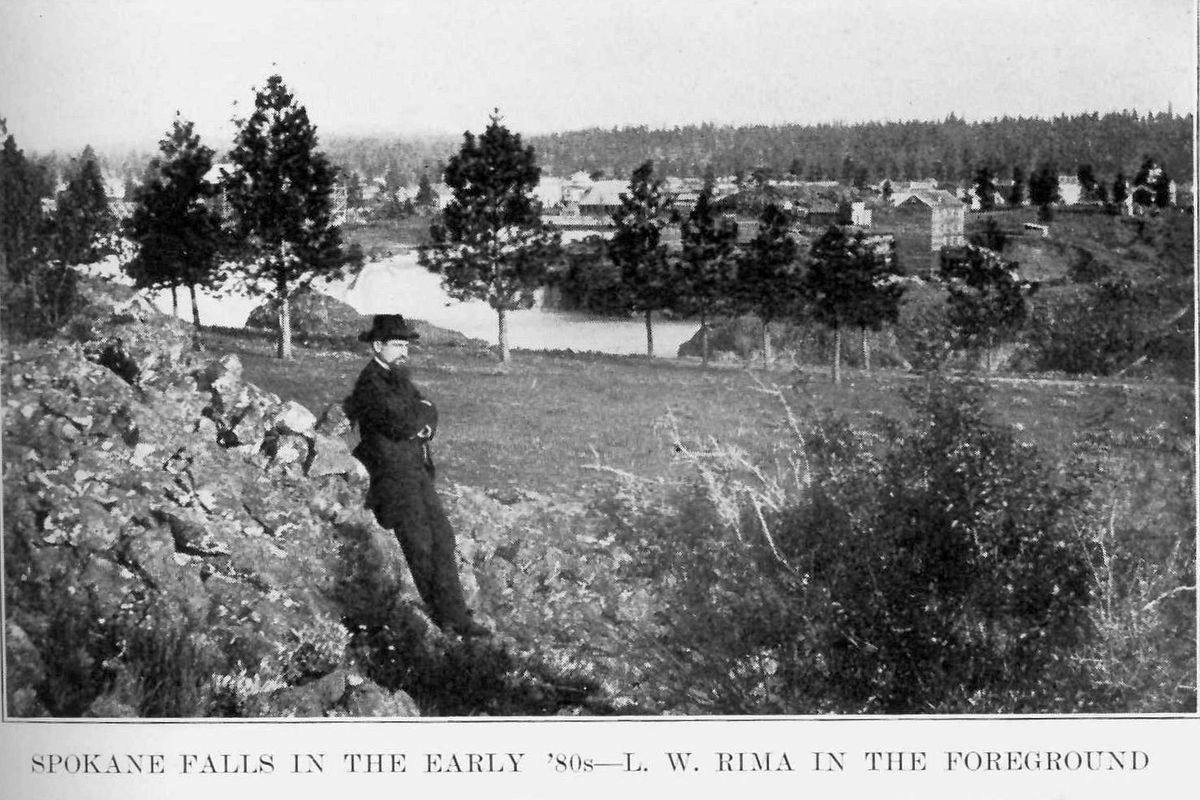

He laid out the first streets of Spokane, but the story got lost over the years. Now, descendants of L.W. Rima are fighting to tell it

Some of Spokane’s early pioneers have streets or schools named for them, or even books written about their lives. Lorenzo Wesley “L.W.” Rima isn’t one of those pioneers.

The story of this man who made the first formal survey of Spokane in 1878, and who has any number of other “firsts” credited to him in the development of what was then Spokan Falls, is largely lost to history, or, at best, is a footnote or paragraph in the historic record.

An effort is taking place to change that, beginning with the Friday rededication of the reconstructed historic monument marking his burial site and the placing at that site of a prestigious Final Point Marker from the National Society of Professional Surveyors. The marker is being set by the Inland Chapter of the Land Surveyors Association of Washington to honor the man who completed that first survey of Spokan Falls.

Carl Strode, great-grandnephew of Rima, and his wife, Dana Strode, have been the force behind the belated recognition of this long-overlooked Spokane early pioneer. An accountant, Dana Strode has been active in genealogy work for some time, having researched and placed grave markers for many of her family members in Minnesota. An electrical engineer, Carl Strode retired in 2010, the year they moved from Pasco to Spokane.

Strode has many old family photos , so in 2014 his wife began focusing her genealogical interests on her husband’s ancestor and was fascinated even with the little she initially found. They visited Rima’s grave at Greenwood Memorial Park and saw that the 5-foot-tall obelisk marking the burial site had fallen from its base and cracked apart.

“All that was left was the base with a pin sticking out of the top,” Dana Strode said. “It was such a dramatic diminishment, and I knew we needed to fix it.”

A cause was born. She had a photo of the original monument, and so – with the help of several groups in Spokane, funding by themselves and other family members, and a generous donation by Spokane Masonic Lodge No. 34 (of which Rima was a charter member in 1880) – a new marble obelisk would be built resembling the original. Complete with the Masonic symbol, the new marker would include the geodetic marker honoring Rima’s survey work in Spokane.

These Final Point Markers, which note the latitude and longitude of the surveyor’s final resting place, aren’t available to just anyone, said Jim McLefresh of the Land Surveyors Association of Washington. Application must be made, and a body of significant work shown. “This man did really good work, including the difficult job of surveying lakes in Minnesota before GPS was available.”

The public rededication ceremony of the refurbished grave monument, which will also be attended by out-of-town family members, is the culmination of that part of the Strodes’ effort to honor Spokane’s forgotten pioneer.

Dana Strode also wanted to learn all she could about L.W. Rima, so she dug into historical records and documents. Aided by Rima’s personal diary, she was able to piece together his story.

Although born in Illinois in 1843, Rima grew up in Minnesota, where he built a sawmill, homesteaded 80 acres, read trigonometry books, became a self-taught surveyor (completing hundreds of surveys in that state) and was elected county surveyor there. In 1876, he moved with his wife, Martha, to Oregon in hopes that the climate would improve her failing health. She died the following year at age 29.

A widower with no children, in 1877 Rima moved to Spokan Falls, a town of about 300 people, and opened one of the earliest stores in the town, a jewelry store on Front Street. There, he sold diamonds, spectacles, clocks, spittoons, firearms, keys and stovepipes, and also operated a photography shop.

In 1878, he surveyed the town at the behest of James Glover, who is considered the “Father of Spokane.” The plat of those 20 blocks set the basic orientation of streets that all subsequent surveyors followed. He also surveyed the original plat of the town of Spangle, Havermale’s Addition in Spokane and a section of Peone Prairie.

Rima, whose name is written into the original Spokan Falls City Charter, was appointed to the first Spokane City Council in 1881 (the final “e” being added to the town’s name that year) by the territorial governor. He decided not to seek formal election the following year, choosing to focus instead on other business and civic interests.

He helped form the first library in the town and was a member of the design and contracting committee for the Howard Street Bridge, the city’s first bridge spanning the Spokane River. He also helped develop the first telephone connection and record and report weather information.

Rima became a major real estate developer, owning land downtown where the intersection of Riverside and Monroe now exists, as well as helping to dig and build Riverside Avenue. One newspaper article also speaks of his fine photography. He noted in his diary that he built a violin and taught himself to play.

In 1879, Rima moved his jewelry store to a site on Howard Street, but when that wooden building burned in 1883, he rebuilt it as one of the first brick buildings in the town, known as the Rima Block. He remained active with Masonic lodges in the communities where he lived throughout his life, and indeed helped charter several of them.

Rima, who never remarried, was a major contributor to the economic and civic life of Spokane. Perhaps he would have been better known and celebrated had he lived longer, but he came down with pneumonia in 1885 and died within a few days at the age of 41.

He was first interred, it is believed, at Mountain View Cemetery, Spokane’s second cemetery, located at 10th Avenue and Cannon Street.

When it was determined the land there would be more valuable for homes, those buried there were reburied elsewhere. His remains were moved to Greenwood Memorial Terrace, where he was laid to rest a second time, in 1889 in the bench section of the cemetery, an area where many of Spokane’s pioneers and famous earliest citizens are also interred.

While his legacy isn’t discussed much today, Carl Strode said his great-granduncle was truly a renaissance man and a well-known presence in his day.

“This is just the beginning,” Dana Strode said. “We want people to know that he was here. We’re not done yet telling his story.”