Working it out

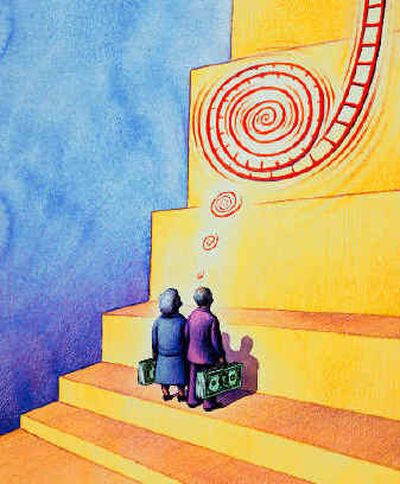

Many married couples reach a point when they must decide whether both spouses retire at the same time.

Experts say husbands and wives often want to coordinate their exits from the labor force. It’s sometimes not that easy. Today’s complicated finances require working couples to weigh both spouses’ benefits, and numerous lifestyle and emotional issues must be confronted.

“We have had a good handful of clients where the wife has called up separately and said, ‘I want you to tell my husband that he can’t retire,’ ” said Peg Downey, a financial planner in Silver Spring, Md.

Too often, spouses don’t discuss their retirement timing with each other.

“I’m always amazed that people seem to be having that conversation for the first time at my desk,” said John Bacci, a financial planner in Linthicum, Md. “Sometimes, you feel like introducing them to each other. How does that not come up?”

The decision to retire together or not used to be much simpler a generation or so ago, said Richard W. Johnson, a senior research associate with the Urban Institute in Washington D.C., who has written on the topic. Back then, husbands were often the primary breadwinners and retirement depended on when he built up enough pension benefits to cover both, Johnson said.

Now, about 62 percent of married women are in the labor force, according to the latest government figures, up from 44.4 percent in 1975. Working couples must figure how to maximize the benefits from each employer, such as whether one should log in more time on the job to collect a fatter pension or maintain generous health care benefits, Johnson said.

Among married couples retiring between 1992 and 2002, both spouses retired within two years of each other in nearly half of the cases Johnson said.

“There is this real tendency … for husbands and wives to try to retire at the same time,” Johnson said. “There are a lot of factors that work against it, that prevents them from realizing their goals.”

Many of those factors are financial.

Often, a stay-at-home mother returns to a job once children are grown and she needs to work longer to become vested in a pension plan or to build benefits, experts said. Social Security considerations can lead one spouse to work longer than the other, too.

Married people can receive Social Security benefits based on their own wage history or up to half the benefits paid to spouses, whichever amount is higher. If one spouse makes significantly more than the other, there is less incentive for the low-wage spouse to work and more reason for the highly paid spouse to stay on the job and build bigger benefits for each of them, Johnson said.

Debt, too, can stall one’s retirement. A spouse with an outstanding 401(k) loan must repay it before leaving the job or end up paying taxes and a penalty on the money, said Christine Fahlund, a senior financial planner with T. Rowe Price Associates.

And mortgage payments might be too steep to comfortably handle if both paychecks disappear, she said.

Health benefits play a big role when partners don’t retire together, planners said. Many employers don’t extend health insurance to retirees, so one spouse might keep working for coverage until Medicare kicks in at age 65, planners said.

When health problems force one spouse to retire early, the other might have to work to maintain affordable insurance coverage, planners said.

When finances aren’t the issue, other factors can lead to spouses not retiring in tandem.

The career of a wife who returned to work after rearing children might just be taking off when her husband is ready to drop out of the work force, Downey said.

For financial planners, crunching retirement numbers is the easy part. Planners sometimes must dig to find the root of emotions that crop up about retirement, such as cases where wives don’t want husbands to retire, Downey said.

In one such case Downey worked on, the wife was frightened by stories of men dying shortly after they retire, so she didn’t want her husband to quit work. More often, the wife encourages her husband to continue working because she doesn’t want him getting underfoot at home, experts said.

Friction from “too much togetherness” is a frequent problem brought on by retirement. Sometimes, a stay-at-home spouse enters the work force once the other retires, planners said.

Some spouses, sensitive to the problem, phase-in retirement to give a partner time to adjust.

“24/7,” Fahlund said, “is a little bit daunting.”