Owners want city to drop beach suit

A group of Sanders Beach homeowners alleges that the Coeur d’Alene city attorney filed a lawsuit over the ownership of the popular beach to benefit his recent run for the Idaho Legislature.

And the group wants the city to drop the lawsuit that asks the court to determine the ordinary high-water mark on the popular shoreline between 12th and 15th streets. The high-water mark shows where private land ends and where publicly owned waters begin.

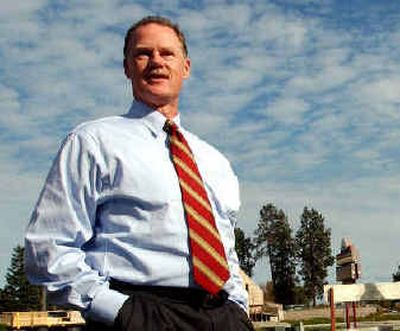

Mayor Sandi Bloem rejected the claims and said that the City Council, not City Attorney Mike Gridley, decided to go forward with the lawsuit as a way to once and for all establish where private property ends and public land begins – ending more than 40 years of argument and debate.

“Any inference that this was done for a political reason by Mike Gridley is out of order,” Bloem said. “Mike Gridley could not have done this without council action. This is what we requested. The city’s concern is to have an opportunity that stands in court as to who owns what, so we know how to protect the public and or private rights.”

Gridley lost his bid for the Idaho House Tuesday night to Republican Marge Chadderdon. The next day Gridley received a letter from local attorney John Magnuson, who is representing six of the Sanders Beach property owners.

Twelve property owners, the Sanders Beach Preservation Association and the Idaho Department of Lands are named as defendants in the lawsuit filed Oct. 19.

The letter alleges that Gridley’s political aspirations “colored” his actions in filing the lawsuit. Magnuson also states that Gridley created a “false issue of uncertainty” about the ordinary high-water mark. Magnuson and his clients maintain that there is no dispute over that mark.

The letter goes on to “assume” that the lawsuit was actually written by local attorney Scott Reed, who represents the Sanders Beach Preservation Association. It states that Reed gave a $925 in-kind donation to Gridley’s campaign while other campaign donations were made by local attorney and preservation association member Ray Givens and his former law firm partner Howard Funke.

Magnuson said he has no proof, other than it “appears” Reed’s word processor was used to write the lawsuit.

“I’ll let people draw their own conclusions,” Magnuson said Thursday. “It’s a conflict that appears to be something to cause an independent person to pause.”

Magnuson said he waited until after the election to send the letter to keep from politicizing his clients’ concerns.

Gridley said that Reed along with other preservation association members did initially pitch the idea of suing all parties that have a stake in the location of the high-water mark.

The preservation association wrote a letter in July demanding that the city, Kootenai County and the Idaho Department of Lands finally determine the high water mark.

But he said Reed didn’t write the lawsuit and that it was penned by Mike Haman, the independent counsel the city hires to handle civil litigation.

“We filed that because we saw an opportunity,” Gridley said. “It will never be resolved until someone determines where the property line is and that’s a means to determine where the ordinary high-water mark is located.”

He added that the city wants to end the fighting and potential for violence. As Coeur d’Alene’s population has grown and the lakefront property has changed owners, the annual summertime clashes have increased.

That’s the same reason Kootenai County Prosecutor Bill Douglas also joined the lawsuit.

Homeowners between 12th and 15th streets believe their property extends to where Lake Coeur d’Alene laps at the sand. Yet many other residents, including the preservation association members, believe the beach is public because people have been using it for years, and they assume its part of the state-managed land, just like the lake.

Homeowners are often upset the city refuses to enforce trespass laws. Beach users are often mad that the city won’t stop homeowners from attempting to kick them off the shore.

Magnuson maintains that Gridley came up with a city policy this summer not to enforce trespass laws on Sanders Beach. He said that the policy has ultimately turned the homeowners’ private property into a public park, without giving the homeowners any compensation.

He added that the policy is based on the false premise that the ordinary high-water mark of the lake is unknown.

Gridley said the city has had that policy for years, long before he became city attorney. He referred to a 1995 memo from the City Attorney Jeff Jones to the Coeur d’Alene Police Department outlining why they can’t enforce trespass laws on Sanders Beach.

Gridley said it’s no conflict that Reed, as a campaign contribution, allowed him to use his mail machine to send out $925 worth of mailings in May, long before the city even thought about filing a lawsuit to resolve the Sanders Beach issue.

Reed said it’s not unusual for him to contribute to Democrats, or even to other attorneys against whom he has litigated. And that’s the same situation with his involvement with the Sanders Beach Preservation Association and Gridley.

He said if Magnuson’s clients disagree with the lawsuit that they should file a motion to dismiss, not argue their case in the newspapers.

Both the city and county say they are neutral parties in the lawsuit and aren’t concerned about the outcome. They just want the court to decide the high-water mark.

Magnuson countered that the city is taking a position by asking the court for an injunction to allow the public to continue to use Sanders Beach until the lawsuit is resolved. He said that shows that the city sides with the preservation association’s claim that the beach is public. He calls the city and preservation association “ideological soul mates.”

Gridley disagreed, arguing the city wants to maintain the status quo – which means allowing people to use the beach – until a judge makes a determination.