Hate’s new home

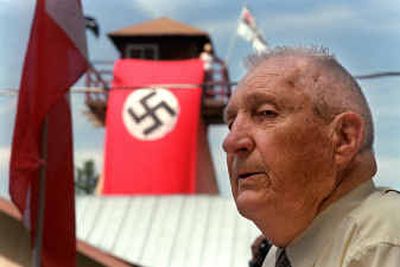

For the first time in 30 years, the Aryan Nations no longer has its headquarters and post office box in North Idaho.

Instead of Hayden, Idaho, the white supremacist organization is now collecting its mail at a post office box in Lincoln, Ala., a small community 86 miles from the civil rights organization that financially bankrupted the Aryan Nations.

The new Alabama location for the “Aryan Nations World Headquarters” was posted on the group’s Web site about two weeks after its founder, Richard G. Butler, died Sept. 8 of coronary disease at his Hayden home.

Now, instead of one person, a four-member “leadership council” is about to be named to succeed Butler.

The late founder of the Aryan Nations “signed off” on the joint-leadership concept at this summer’s Aryan World Congress, just eight weeks before his death, said Laslo Patterson, of Talladega, Ala., who holds the rank of “major” in the organization.

The relocation may answer a question many have asked this past month: Does Butler’s death finally spell an end to the organization he founded, at least in this part of the world?

While the organization has a new address in the Southeast, experts say the specter of Butler and the Aryan Nations likely will linger in the Northwest. The possibility remains that the group’s annual World Congress will continue to be held in North Idaho each summer. And there are other racist, anti-Semitic groups and individuals in the region.

“Our new post office box is not in your back yard anymore, but the Aryan Nations still is,” said Jonathan Williams, Aryan Nations communications director in Atlanta.

“We are carrying on the wishes of Pastor Butler,” Williams said of the change in leadership style. “No one person can fill his position, in my opinion.”

Butler’s suburban rancher on Skyview Lane in Hayden became the group’s headquarters in 2000 when the 20-acre compound, built in the mid-1970s, was sold in a bankruptcy sale to partially satisfy a $6.3 million civil judgment. Butler repeatedly vowed the Aryan headquarters would never leave North Idaho.

“There will be no single leader any longer,” Patterson said when asked about the move to Alabama. “Aryan Nations will be run by a four-member council.” He wouldn’t say if he would be one of the four new leaders or if he is now picking up the organization’s mail at the post office in Lincoln, near his home.

Longtime Aryan Nations member Rick Spring, who lives in Arkansas and couldn’t be reached for comment, is widely mentioned by experts and people within the movement as one of the likely leaders.

The four names are expected to be announced in the next few weeks.

“There’s no hidden agenda there,” Patterson said when asked why the Aryan Nations headquarters was now less than 100 miles from one of the group’s archenemies, the Southern Poverty Law Center.

“I just think people in the Southeast United States are more geared to the Christian Identity movement than elsewhere,” Patterson said.

Patterson has ties to the Alabama White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, which became known as the Aryan Nations Knights of the KKK after Butler made a trip to Alabama in January 2003.

The Aryan Nations embraces a Christian Identity religious belief that white people are the true children of God, the real Israelites, while Jews are descendants of a sexual union between Eve and Satan, and that nonwhites are “mud people” without souls.

As an extension of that belief, Butler and his followers idolized Adolf Hitler and Nazism, and they embraced the racist, anti-Semitic dogma of the Ku Klux Klan.

Over the past decade, Butler had named Neuman Britton, of California, then Ray Redfeairn, of Ohio, as his successors. But they both died before he did.

If he agreed to the idea of a leadership team, as Williams and Patterson claim, Butler may have taken a cue from a rival group, the Church of True Israel, composed largely of his ex-followers. Based in Coeur d’Alene, that Christian Identity group was set up in 1995 by a “five man Council of Senior Prelates.” “We have avoided the pitfalls of a one-man rule,” the Church of True Israel’s Web site said in 2000.

The group held a private gathering in July near St. Regis, Mont., the same July weekend Butler held his last Aryan World Congress and parade in downtown Coeur d’Alene.

“Obviously, the future of Aryan Nations is still murky,” said Mark Pitcavage, national fact-finding director for the Anti-Defamation League.

“The loss of the compound and the lack of a clear successor have dealt serious blows to Aryan Nations,” Pitcavage said.

The white supremacist group also has been affected by a series of arrests, according to Pitcavage and other experts who track extremist groups.

Two weeks after Butler’s death, Aryan Nations Nevada leader Steve Holten, who marched in Coeur d’Alene in July, was arrested on federal charges accusing him of e-mailing threats of violence to Jewish and minority leaders in California and Nevada.

His threats, directed at Jews, minorities, gays, law enforcement and media representatives on a “most-wanted list,” promised “terrorist actions that will be gruesome and something that has never been seen,” court documents state.

Earlier this year, Aryan Nations member Sean Gillespie, formerly of Spokane, was arrested on charges of firebombing a synagogue in Oklahoma City. In Longview, Wash., Aryan Nations member Zachary Beck was arrested on charges of shooting at police. And in Montana, Aryan Nations member Karl Gharst was arrested on charges of threatening to kill a social worker.

Pitcavage said Charles Juba, who leads an Aryan Nations splinter faction in Pennsylvania, “would like to assume the mantle of Aryan Nations leader, but few people support him and he has little influence beyond his immediate circle,” which includes ex-Posse Comitatus leader August Kreis.

After Butler’s death, the Pennsylvania faction said James Wickstrom was the new “national chaplain” of the Aryan Nations. He did not respond to an e-mail request for comment.

“It is still possible that Aryan Nations may limp along until someone with charisma and organizational abilities comes along to revive it,” said Pitcavage, referring to the revival of the World Church of the Creator under Matt Hale years after the suicide of its original leader.

“After all,” Pitcavage said, “Aryan Nations is a powerful ‘brand’ in the white supremacist movement. In the months or years to come, many might vie to follow in the footsteps of Wesley Swift and Richard Butler.” Swift, also deceased, was Butler’s predecessor in the Christian Identity movement. In the interim, or in the absence of an Aryan Nations revival, other groups are likely to benefit from Butler’s death, he said.

‘End of an era’

At the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, Ala., hate group expert Mark Potok said Butler’s death “marks the end of an era.”

“Butler was successful in bringing together key factions of the often-splintered radical right, and also in spreading his Christian Identity philosophy throughout the movement, but by the time he died, his only importance was as an aging icon of the extreme right,” Potok said.

Moving the Aryan Nations headquarters to Lincoln, Ala., “gives a feeling for how weak the organization has become,” he said.

“At the same time, it should be noted that at the time of Butler’s death, his faction had some 17 active chapters and more than 150 members. But, at the time of his death, Butler was holding his group together with only bubble gum and string – the Internet and the telephone – and he leaves nothing but his personal legacy. There is no compound, money or other property to be fought over.”

“For the moment, we expect Butler’s faction of Aryan Nations to move ahead under committee leadership,” Potok said, predicting a possible power struggle.

It’s unlikely the Aryan Nations “will disintegrate immediately, but if it survives, it will likely need a single charismatic leader,” he said.

Brand name in hate

Other experts said part of Butler’s legacy was that he made “Aryan Nations” a brand name in white supremacy circles.

“Unlike some, I do not believe Aryan Nations is anywhere near dead and buried,” said analyst Rick Eaton at the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a Jewish human rights organization in Los Angeles.

He predicted “any number of people will take a run at” attempting to fill Butler’s shoes. “The name ‘Aryan Nations’ is too important to let die with Butler or turn over to a nut job,” Eaton said.

“The good news,” he said, “is that I believe that any revival is unlikely to take place in northern Idaho. While that might be a spiritual gathering place in the future, actual leadership is likely to surface somewhere else.”

Another expert, Lenny Zeskind, of Kansas City, said he sees the National Alliance filling some of the void created by Butler’s death. Its leader, William Pierce, died in 2002, but the organization “is still intact and stronger than any other single competing outfit,” Zeskind said. Pierce wrote a novel that in the early 1980s inspired The Order, a group of neo-Nazi terrorists, most of whom came from Butler’s church.

Zeskind predicted the National Alliance and other hate groups will focus on immigration issues to attract followers. “On this point, clever white nationalists, sans the usual uniforms, will be inserting themselves and recruiting the next generation of activists.”

“It will be the white nationalists without tattoos and without uniforms who will pose the greatest danger,” he said. And that danger today is as great as it was on Jan. 1, 1986, after The Order trial had been concluded with more than two dozen convictions.

Members of The Order printed counterfeit money on a press at Butler’s Hayden compound and then robbed armored cars in their attempt to start a race war. The group carried out bombings and murdered a Jewish talk radio host before being rounded up by the FBI in 1985.

The legacy of that group of domestic terrorists is well-remembered at the American Jewish Committee headquarters in New York, where Ken Stern also said Butler’s passing “certainly marks an end of an era, but not of the problems the Aryan Nations presented.”

“History teaches that there will always be ideologies and theologies which preach hatred, and that it is the responsibility of all of us to take those messages seriously,” Stern said.

“To me the great story of the Inland Northwest was not Butler, but how people such as Bill Wassmuth, Norm Gissel, Tony Stewart, Marshall Mend and many others organized to combat the neo-Nazis,” he said.

“I worry less about what new personalities and formations might emerge from hate groups, and more about how their message might gain some traction in the decades ahead as America becomes a nation with a majority of nonwhites,” Stern said.

He also said one indirect part of Butler’s legacy was the creation of the Gonzaga Institute for Action Against Hate in Spokane.

“Without the hate crimes of Aryan Nations members, it is questionable whether the institute would have been formed,” Stern said.

“It is the one institution in the country, perhaps the world, dedicated to creating an interdisciplinary field of hate studies, to help us all better understand how hate works, and how best to combat it,” Stern said.

One of the institute’s founders, George Critchlow, said the advent of the Internet and electronic communication has changed everything. “Haters now exist and communicate in a community with no physical bounds or dimensions,” said Critchlow, dean of the Gonzaga School of Law.

Hate groups don’t need a physical headquarters, because “they have the ability to connect with and influence receptive audiences anywhere, anytime,” he said.

“Richard Butler’s Aryan Nations compound has given way to Web sites with the capacity of projecting hatred, prejudice and misinformation into places and lives undreamed of by traditional haters,” Critchlow said.

Butler was buried in a private ceremony on Sunday, Sept. 12, at a cemetery in Coeur d’Alene. Several visitors already have stopped by, but only a metal vase of plastic dogwood blossoms marked the spot last week. The headstone for the World War II veteran is being prepared by the U.S. government that Butler despised so much.

When it was time to dig Butler’s grave, there were two gravediggers at the cemetery – a white man and an American Indian.

The Native American said he wasn’t told about the burial or asked to do the work. But he said he would have welcomed the opportunity to throw the last shovelful of dirt in the grave of one of the world’s leading racists.