Legacy of contamination

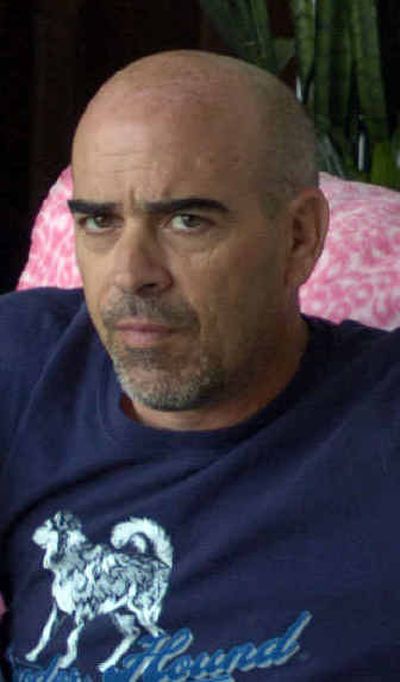

The fuel leaks found recently at BNSF Railway’s refueling depot north of Post Falls have gotten under John Hiatt’s skin.

The Spokane tavern owner doesn’t consider himself an environ- mentalist, but he knows a thing or two about the company. He doesn’t believe railroad officials’ claims of being able to fix the underlying causes of the fuel leaks at the Hauser depot, or that the troubled depot doesn’t pose any threats to the region’s drinking water aquifer.

More than a foot of diesel floats on the groundwater below parts of Hiatt’s hometown of Livingston, Mont. There have been diseases, early deaths and miscarriages in Hiatt’s family that he blames on the water, though no independent tests have verified that opinion. When Hiatt learned that traces of diesel have already been found in the aquifer below BNSF’s Hauser depot, he felt a knot in his stomach.

“I want these people to realize what type of mess they could be getting into,” said Hiatt, who added that he will never forgive BNSF for poisoning Livingston. “It was like Mayberry. Now it’s like Mayberry on acid.”

Hiatt played his own part in the pollution, a fact he readily admits. Before moving to Spokane a decade ago, he worked for BNSF and once obeyed a foreman’s orders to drain a full tank of diesel from a locomotive – about 3,600 gallons – onto bare dirt. The tank needed to be welded, the foreman told him.

BNSF is now pouring millions of dollars into repairing its Hauser depot, and the railroad insists it is committed to protecting the Rathdrum-Spokane Valley aquifer from further contamination. Railroad officials have said the company now makes environmental stewardship a top priority. But pollution from BNSF taints aquifers in communities across the West. Residents in some of these towns say the railroad continues to put profit over purity and then fights cleanup efforts.

“BN means bad news,” said Jim Jensen, a Montana environmental activist who has been working for nearly 20 years to get the railroad to clean up polluted sites in more than a dozen cities across the state. “Every place they operate they contaminate the water. You can’t trust them. The only thing you can trust with BN is they will contaminate your water and they will try every political trick to keep from being regulated and to keep from being prosecuted.”

BNSF spokesman Gus Melonas said the company is working “aggressively” to repair the Hauser depot, as well as other sites dirtied by the company. Although Melonas declined to discuss allegations of company foot-dragging or political influence peddling, he issued the following statement: “We’re not leaning on political connections. We’ve been upfront.”

Major cleanup efforts are getting started at some of the company’s polluted sites.

About 600,000 gallons of pure diesel have been vacuumed out of the aquifer below Mandan, N.D., but an estimated 3 million gallons remain. BNSF recently agreed to pay the city a $29 million settlement for the contamination, which was caused by leaks at a refueling depot, said Mayor Ken LaMont.

“It’s a sad deal,” LaMont said. “It was our central business district.”

LaMont speaks about the business area as if it’s already gone. The real estate has been rendered essentially useless by a 5-foot-thick plume of diesel less than 10 feet underground, he said. Petroleum fumes are overpowering in some buildings, and downtown now needs to be moved and rebuilt.

“Our central business district is null and void,” he said. “Banks won’t finance contaminated properties.”

‘Cheaper in the long run’

The contamination, caused by a “combination of leaks and carelessness” over many years, was discovered 20 years ago, but little was done to fix the problem until the state of North Dakota intervened in 2002 and sued BNSF, LaMont said.

“They were so slow, we finally had to push them,” he said of BNSF. “I have some hard personal opinions. I need to be careful about what I tell you because of the settlement. Basically, they were very difficult to work with.”

Melonas would say only that the company has agreed to a settlement with the state of North Dakota.

More than 70 years ago, local government officials warned the railroad to clean up its act in Skykomish, Wash., a tiny mountain town 90 miles east of Seattle. Locomotives heading up steep tracks in the Cascades once stopped in the community for loads of fuel oil and traction sand. The oil was stored in large vats, which leaked into the nearby Skykomish River.

Even though the railroad had been warned to halt the pollution as far back as the 1930s – the rail yard master was even arrested at one point, according to historical records – only now are cleanup efforts beginning in earnest, said Michael Moore, a teacher and founder of the Skykomish Environmental Coalition.

Moore gives credit to local high school students, who made a video of the pollution, including scenes of steelhead migrating upstream through a rainbow sheen of oil. “That broke this whole place open,” he said. “Believe it or not, it was the fish. That’s what’s pushing a lot of this.”

Moore’s house will likely be moved as part of the cleanup. Heavy oil contaminates the aquifer 15 feet below the home. On hot August afternoons, Moore can sometimes smell the fuel. When community members recently put in a septic tank at the community center, “We accidentally struck oil,” Moore said.

The oil is heavy, with the consistency of molasses. It’s not easy to remove from the aquifer, but state law requires a full cleanup, said Louise Bardy, cleanup manager for the Washington Department of Ecology. The state is currently negotiating a cleanup plan with the railroad.

Local residents are being given numerous chances to weigh in on the proposals and have even been given a grant by the state to encourage their participation. Costs range from $80 million for a “squeaky clean” state proposal to a railroad proposal with a $22 million price tag, Bardy said.

BNSF stopped its refueling operations in Skykomish in the 1970s. Bardy said she can’t explain why the cleanup has taken so long.

“It’s just a way that a lot of big companies operate. It’s not just the railroad sites. Some of the bigger industries just fight to not do anything,” Bardy said. “It’s cheaper in the long run to pay attorneys’ fees than take care of the problem.”

Big Sky pollution

Bardy and Moore both say BNSF has been cooperating lately to clean up the mess, although the cooperation has come only after a significant fight. An underground barrier stops most of the estimated 160,000 gallons of underground oil from leaking into the nearby river, but up to 15,000 gallons coat a flood protection levee and continue to ooze into the river. BNSF has attempted to protect the river by employing floating oil capture booms.

The town’s drinking water source is upstream from the contamination, but the mess has caused property values to drop, Bardy said. Some residents now have difficulty obtaining home equity loans.

Bardy said she expects a full cleanup of Skykomish within five years.

At BNSF’s former and current refueling depots in Montana, there’s little optimism for full cleanups anytime soon. The railroad has 25 polluted sites across the state, according to a rough count by Denise Martin, site response section manager for the state’s Department of Environmental Quality.

BNSF fuel depots have tainted aquifers below many of the state’s cities, including Billings, Butte, Havre, Missoula, Great Falls, Glendive, Helena, Livingston and Whitefish. Of 208 polluted sites on the state’s cleanup priority list – ranging from oil refineries to old city junkyards and tanneries – 17 are from BNSF. No other business has more than two sites on the list.

Although Martin said BNSF might have completed cleanup on one “relatively small site,” she was stumped when asked whether the railroad had fulfilled its cleanup obligations anywhere else in Montana.

“Doggone it, let me think,” she said, adding moments later, “It has been a struggle to get a lot of the work done that the agency thought needed to be done. BN, of course, wants to minimize the costs at these facilities.”

Melonas, the BNSF spokesman, disagreed and said the railroad has cleaned up some of its contaminated properties in Montana and the company continues to “aggressively pursue cleanup” at other sites.

“Some of those sites have been corrected,” Melonas said. He could not provide details when asked for specifics. “I don’t know which ones.”

Closed-door meetings

More than 20 years after thousands of gallons of diesel and toxic solvents were found in Livingston’s drinking water source, the state is still working with BNSF for a complete cleanup.

A major sticking point has been trying to get the railroad to agree to remove the pure diesel that floats atop the aquifer, Martin said. The toxic solvents are an even bigger worry and harder to clean because they have dissolved into the water. No such solvents have been associated with the spills at the Hauser depot.

Although lawsuits have been filed and agreements made, the state of Montana is unable to make any outright demands for cleanup from the railroad because of a special review clause granted to BNSF by previous leaders at DEQ. With any other company, “We’re not negotiating with them,” Martin said.

Martin did not want to speculate why such agreements were made – it happened before her time at the agency, she said. Others say the sites don’t just stink of oil, they reek of political connections. BNSF’s attorney for much of the Livingston cleanup fight was a man named Leo Berry, who previously served as commissioner of State Lands and the director of the state’s Department of Natural Resources and Conservation. Former Montana Gov. Marc Racicot now serves on BNSF’s board of directors.

“BN wields a lot of political clout in Montana,” said David Scrimm, the former technical services bureau chief for Montana DEQ.

Scrimm, now an attorney for the Montana Wilderness Association, said DEQ employees pushed hard for a faster cleanup but their efforts were rebuffed by Racicot and the previous governor, Stan Stephens, who served from 1989 to 1993.

In the late 1980s, shortly after the full extent of the pollution in Livingston was discovered – two city wells needed to be shut down and BNSF had to supply some local residents with bottled water – Stephens replaced a state attorney handling the negotiations with the railroad with a political appointee and then allowed the discussions to proceed in secret, according to various press accounts from the time.

The meetings were accidentally discovered in 1989 by Jim Jensen, executive director of the Montana Environmental Information Center. Jensen was in a state office building when he spotted BNSF attorneys walking into a conference room with state officials and closing the door behind them. Jensen walked in and refused to leave. The meeting was promptly adjourned, Jensen recalled recently.

Critics of the Hauser depot say politics and backroom deals trumped science and common sense when Kootenai County voted 2-1 to approve BNSF’s request to build a high-speed refueling depot above a federally protected drinking water aquifer.

Facing steep opposition across North Idaho and Spokane, BNSF hired the Gallatin Group in 1998 to direct a campaign to gain approval for the site.

The Gallatin Group, a leading Northwest public relations firm, employs former four-term Idaho Gov. Cecil Andrus. One of the firm’s partners, John Etchart, is a former BNSF vice president and political appointee of Montana Gov. Racicot.

The Gallatin Group’s Web site uses the Hauser depot as a case study: “The Gallatin Group worked intensely behind the scenes taking advantage of its extensive connections in both north Idaho and Spokane to build support for the facility and to blunt the opposition’s initiatives.”

Repairs and testing are continuing this week at the Hauser depot, which was ordered closed nearly two months ago by Kootenai County Judge Charles Hosack. The railroad returns to court Thursday and is expected to argue that its facility is safe to resume refueling operations. Seals have been tightened on the leaking underground fuel protection barrier and special wells have been drilled to help vent leaked diesel from the soil and groundwater.

Although details of the repairs are expected to be revealed at the court hearing Thursday, the railroad has refused numerous requests by The Spokesman-Review to observe work at the site. The Idaho Department of Environmental Quality has been negotiating in private with the railroad to develop a cleanup plan. Agency officials have refused to discuss any aspect of the settlement talks.

Jensen, the Montana environmental activist, said he is saddened by the news of BNSF’s fuel leaks in North Idaho. He said he once thought the railroad’s record of pollution and foot-dragging in Montana would have served as powerful ammunition to stop its plans for North Idaho. In 2000, Kootenai County commissioners granted BNSF permission to build the refueling station.

Although Jensen gave advice in the late 1990s to local residents who fought the depot, he expressed regret for not working harder. A conflict prevented him from traveling to Coeur d’Alene in 2000 to testify at a hearing about the construction of the facility.

“I still feel bad about that,” he said.