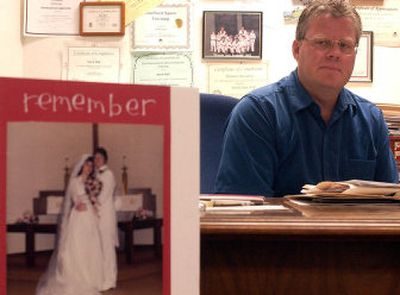

Through sickness and health

It was Mark Hall’s 20th wedding anniversary, and he was pulling out all the stops. The diamond earrings he’d bought his wife, Lori, at a local pawnshop a year earlier were coming home. He’d planned to fly his bride over the Grand Canyon and get down on his knees all over again.

“In a helicopter,” Mark said. “My plan was to fly over the Grand Canyon in a helicopter. I wanted to renew our vows.”

Lori loved her husband’s surprises. She always did. Except this time she had a secret of her own to share, one that scared her badly enough that she’d hidden it from herself as long as she could. There was a lump underneath her skin, growing just above her left collarbone. She didn’t know if the lump was cancerous and, for a while, took an uneasy comfort in not knowing, but it was getting harder to ignore.

So on their 20th wedding anniversary, in 2003, the couple sat in the lobby of a Spokane clinic waiting for the results of Lori’s biopsy, thinking not of their wedding vows, but of how they were going to tell their two children if the results were bad.

And the results were bad. Lori, 40 years old, had pancreatic cancer, which had spread through her body. Doctors were giving her three months to live. The Halls went home and told their children. Tony, an eighth-grader, ran to the laundry room, lay in front of the dryer and refused to move. Ashton, a West Valley High School freshman at the time, listened to the news shellshocked.

Mark clung to the good news of the day. Alone with his wife in the living room of their home, he got down on one knee, produced the earrings he’d intended to present over the Grand Canyon, and reiterated his commitment to love and cherish, honor and obey, through sickness and health until … well, they weren’t going to talk about the last part. Lori wanted to focus on beating the odds, doctors gave her and nothing else.

“From the very beginning, she didn’t want to know,” said Linda Hoff, a close friend of the Halls. Hoff took turns with Mark driving Lori back and forth between Seattle for chemotherapy and radiation treatment. “Lori didn’t want to know if the cancer was on the tip of her pancreas, or anything. She didn’t want to know because she was afraid.”

Mark paid attention to the details, his wife’s white blood cell count, the shadows that turned up on body scans as doctors searched for more tumors. He went online and looked up the odds of surviving pancreatic cancer; fewer than 20 percent of all patients lived beyond two years.

Lori turned to Christianity, which led to Bible study groups and prayer chains for her health. At times, she and her husband would kneel as their congregation encircled them and prayed for Lori’s well being. They asked God for the strength to live with whatever came next.

So many people were praying for Lori that her husband started a weekly, sometimes daily diary on the Internet to keep everyone posted on his wife’s progress. The diary, online at www.emtsurvey.com/ LoraMar.htm, was Mark’s. His wife focused on getting well. Nearly every entry, and the entries went on for 122 pages, began the same way. “A very good week.” Lori’s energy level was always surprisingly good, given the chemo drugs she was taking and the radiation intended to cook the cancer cells from her pancreas. Maybe the cancer wasn’t going away, but it wasn’t spreading, and the couple saw life’s glass as half full.

Lori was beating the odds, living six times as long as doctors predicted she would. She and Mark were doing it together, making the best out of a bad situation, just as they did in their first years of marriage, when Lori worked to put her husband through school, when their first two attempts at having children resulted in two tubal pregnancies, when all they could see in the night sky was the flash and flicker of Hollywood because the only home they could afford was a trailer on the edge of the Geiger drive-in movie theater.

The Halls just worked harder, just tried to have a family again, just opened their trailer house windows wide so they could hear the sound and watch the movie.

Throughout the cancer treatments, the Halls kept their kids busy. Ashton and Tony were so immersed in sports they hardly had time to think about their mother. Mark’s online diary mentioned only Lori’s health and their children’s activities.

Those who didn’t know Mark and Lori never would have guessed they had jobs by reading Mark’s Internet postings. They did work. Mark worked in computer services at Spokane Community College. Lori worked at the school’s help desk, even as she traveled weekly for cancer treatments in Seattle. Co-workers bolstered her salary by donating more than a year’s pay in sick leave.

Mostly though, Lori was there – to everyone’s amazement. She could be low in white blood cells and sickened by the sight of food, yet she still ate, still worked, still showed up to cheer whenever her kids had a baseball or softball game.

Her cancer doctor, Vincent Picozzi, credited Lori’s stamina to her will to see her children grow and some deep inner strength, drawn from her belief in God.

She joined the 20 percent of pancreatic cancer survivors who cross the two-year mark, even gained a four-week respite from being poisoned and radiated before her health began to slide. Lori contracted pneumonia-like symptoms in June and by July was confined to a hospital bed. This time doctors were giving her days to live, and they weren’t proven wrong.

Lori conceded that her fight was over. She wrote for the first time on her husband’s Internet diary and asked everyone to pray for their family as they had prayed for her, to be there for her children as they had been for her.

The Halls, Aston, Tony and Mark, gathered around Lori’s bed and waited for the end. The couple had arrived at that final wedding vow, the one they hadn’t talked about 28 months earlier. The one they wouldn’t bring up now.

Just go find us a trailer, Mark told his wife, open the window wide and wait for me. I’ll be home soon.