Dusty to digital

MADISON, Wis. — It’s a stately old building with looming columns, worn marble stairways and arched doorways — dedicated in 1900 “to the conservation, advancement and dissemination of American Heritage.”

But while the Wisconsin Historical Society contains one of the largest American history archives anywhere, fewer people have visited in recent years — 40 percent fewer than in 1987 — as more of them, including students at the nearby University of Wisconsin, turn to the Internet as their basic research tool.

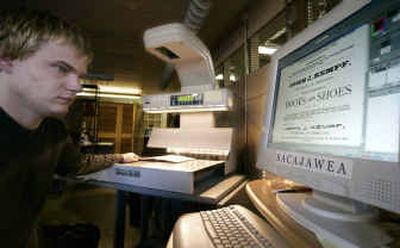

So the historical society and many other institutions with large collections are doing something they see as means of survival: They’re going digital — creating and uploading images of many items in their collections for all the World Wide Web to see.

“History belongs to everybody; it shouldn’t be locked away in dark rooms,” says Michael Edmonds, deputy administrator of the Wisconsin Historical Society’s library-archives division. “It should be on everybody’s laptops at Starbucks.”

The movement to “digitize” collections received a lot of attention last month when popular search engine Google announced a deal with several university libraries to put their books — or snippets of those books — online. Users would have greatest access to books with content that’s not limited by copyright constraints.

But even before Google began scanning books, many libraries, archives and museums had already been quietly digitizing their most popular and rarest of collections and, increasingly, creating Web sites that put those collections in context.

It’s a trend that Edmonds calls “revolutionary” — and necessary.

“Our future depends on us being able to turn our collections inside out — to show people what we have,” he says.

Starting in 1999 with a $100,000 gift from a retired Wisconsin professor, staff members at his institution have been using some of their limited funds to scan thousands of digital images of rare older books and archived letters.

One result has been a Web site called American Journeys, which details eyewitness accounts of early exploration in this country and includes such rare maps as the first published drawing of the entire Mississippi River, done by French explorers in the late 1600s.

By many accounts, the site has been a success. While the society’s building, which contains about 30 miles of library and archives shelves, attracts about 50,000 visitors a year, American Journeys and other online content taken from those shelves is already drawing more than 85,000 unique Internet visitors annually.

In other words, nearly two-thirds of the people now using the Wisconsin collections are viewing them online.

Archivists across the country are seeing similar results.

“The best thing about it is that we’re able to get materials into the hands of people who would never have gotten them,” says Lee Ann Potter, head of education and volunteer programs at the National Archives & Records Administration in Washington.

She recalls an e-mail from a man living near the Arctic Circle in Alaska. While surfing the National Archives site, he was excited to find an image of the $7.2 million check that the United States used to buy his state from the emperor of Russia in 1868 — just one of millions of images that can be found through a Web search.

Internet surfers can also view a digital image of Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Mona Lisa” at the Louvre Museum’s site and — within a matter of moments — check out Henri Mattise’s “Woman with the Hat,” which is included in the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s online collection.

Lesser-known museums — from the Hockey Hall of Fame to the American Academy of Ophthalmology’s Museum of Vision — have online collections, too, as do many universities.

There are challenges to maintaining these digital archives, though. Steven Hensen, who helps oversee Duke’s rare book and special collections, notes that even books in the poorest condition can survive for decades, if not longer. “We’re not at all sure of this with digital material,” he says.

There’s also the fact that, generally, only a small portion of many archived collections are available online.

The National Archives site, for instance, includes such popular items as the Declaration of Independence and the Emancipation Proclamation. But most of the 8 billion textual documents the federal institution houses are not available online.