Wireless device offers window into heart

From the computer in his office at Sacred Heart Medical Center, Dr. Nour Juratli can peer into a human heart 100 miles away.

He won’t, he said, at least not in front of visitors, out of respect for the privacy of the patient who last month became the first in Washington to receive a cardiac device expected to change the way erratic rhythms are monitored and treated.

Juratli has no doubt that Dean Mahoney, 76, a retired doctor from Lewiston, will benefit from the piece of wireless technology implanted just below his right collarbone.

“For this gentleman, it was not speculation that it would help,” said Juratli, 39, an electrophysiologist.

Mahoney suffered from episodes of ventricular tachycardia, periods when his heart would speed to 240 beats a minute, raising the possibility of fainting – or death.

“It’s dangerous between 180 beats to 300 beats a minute,” Juratli said. “The faster the arrhythmia, the more dangerous it is.”

On June 22, barely a month after it gained approval from the federal Food and Drug Administration, Juratli determined that Mahoney’s best hope was the new Medtronic Concerto defibrillator.

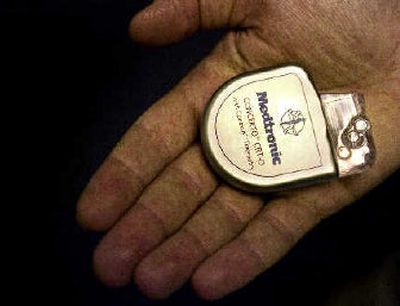

The $25,000 device, about the size and shape of a keyless car remote, is the first of what Juratli expects to be a new generation of cardiac care products. Using a proprietary technique, the implant allows wireless data transmission from the patient to a home monitor up to 16 feet away and then to the doctor’s office by computer.

From afar, the doctor can monitor and evaluate treatment through reports sent by the device, Juratli said. Soon, the device will also be able to send emergency alerts when things go wrong.

At the same time, the implant is a defibrillator – with a twist. Like similar devices, it aims to synchronize the heartbeat, keeping it in line with a firm, often painful, shock, if necessary. But the Concerto also offers a new feature, the option for low-scale electrical impulses that provide painless “pacing” before a shock is required.

It also uses electrical pulses to measure the level of fluid near the heart and lungs, monitoring dangerous build-up weeks before it is normally detected by the doctor, or even the patient, Juratli said.

Heart failure is the No. 1 cause of hospital admissions in the United States, affecting about 5 million people annually. Fluid accumulation in the chest area accounts for most of those admissions, according to hospital officials.

For Juratli, the device’s individual attributes are attractive, but its versatility is most compelling.

“When you get patients who get sick in several directions, you want as many functions as possible,” he said.

Mahoney didn’t want to discuss his new device in detail. He acknowledged that his case was unusual, but said he was getting along just fine.

Nationwide, Medtronic has released a few hundred of the new devices for implantation, said Tracy McNulty, a spokeswoman who declined to release specific figures. The operation is still so rare that patients must require the device and company representatives are present when they’re implanted.

“They’re so new; it’s not like you have them on a shelf,” she said.

Cardiac implants accounted for about $3.8 billion in sales for Medtronic during the nine-month period that ended Jan. 27, according to federal Security and Exchange filings.

Devices like the Concerto implanted by doctors like Juratli represent the future of cardiac medicine, said Dr. Michael Ring, medical director for cardiac services at Sacred Heart.

“This is something that you’re going to see more and more of,” he said. “It gives you the ability to keep an eye on your patient’s heart 24 hours a day.”

Of course, every new device has the potential for problems. Last year, the FDA issued a recall for certain Medtronic defibrillator implants in which batteries shorted out, causing the devices to fail. The firm is facing 114 lawsuits in federal court and 26 in state court for claims of personal injury or compensation, SEC records showed.

“There is always, always worry that a recall will happen,” Juratli said, emphasizing that problems are rare compared with successes.

“No matter how good you are, there’s always pressure to get better.”

The best doctors recognize the point of that pressure, he added.

“We get so much excited about technology, but we should never lose sight of the human person,” he said. “I am fortunate and my patient is fortunate.”