Bennett reaches last stop on tour

LOS ANGELES – As a high school senior on his way to becoming Wisconsin’s Mr. Basketball, Tony Bennett couldn’t believe he was getting the cold shoulder, and getting it from the most unexpected person.

Dick Bennett, his father and the head coach at Wisconsin-Green Bay, had collected oral commitments from a number of other high school prospects. So the coach told his son: Make a decision soon, or I’m giving my remaining scholarship to another player.

“I don’t know if he was playing it cool,” the father said. “I think he was just baiting me – that’s what he was doing. So I finally said, ‘Look, if you’re not going to commit, I’ve got to find somebody else.’ “

The son said he genuinely had hoped to take at least one additional campus visit. So when the next night’s high school game arrived, the son decided to show the father just how angry he was … by scoring 46 points on a helpless foe – and sneering at his father in the crowd every time he added to his point total.

Days later, with the scholarship offer still on the table, the son told his father that he’d be coming to play for him.

“In my mind, I knew I was going to play there,” Tony Bennett admitted, the grin spreading over his face.

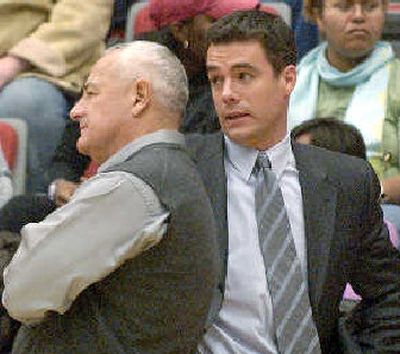

That was nearly 20 years ago, and now the father is making good, in a way, by leaving his son on his own. Dick Bennett has already announced that this, his third season at Washington State, is his last, and his son will be taking over his father’s vacated office. Tonight’s Pac-10 tournament game against Oregon could well be – and based on the recent play of WSU should well be – the last of the 62-year-old’s 40-year coaching career.

The Cougars have lost 13 of their last 15 games this season, hardly the way a coach like Bennett hoped to leave the game. But even this painful final trek from fall practices through the conference season hasn’t affected the coach’s feelings for the sport that gave him a career.

“I always loved it,” said Bennett, who first realized he wanted to coach as a sophomore in high school. “I just thought the team, the chemistry – it was the one sport where I thought you could be better than your parts. I don’t know many sports where that allows.”

Bennett’s coaching career, which took him from five Wisconsin high schools to three universities in the University of Wisconsin system before arriving in Pullman for his final stop, will be remembered for maximizing that ability to make the team greater than its individual players.

It’s a style that harkens back to another era in basketball. Bennett, even if he won’t publicly admit it, relishes the fact that his teams provide a link to the way the game used to be played.

“I don’t even know if he thinks he’s a throwback,” said his brother, Jack, who last year retired after coaching Wisconsin-Stevens Point to two Division III national championships. “But I do think, he really in his mind has this idea of what good basketball is, what good team basketball is. It is about making it real hard for your opponent to get a good look every time down. And it is about not being loose with the basketball, hunting down good looks every time down. And it’s about battling physically and not backing off, no matter what your talent level is.”

Perhaps that explains why Dick Bennett is as competitive now as he was decades ago as a high school coach. Just hours after his impending retirement was made official, Bennett told one story after another to a small group about games from high school gyms, lamenting the missed shots and blown assignments with a stunning degree of specificity. It also explains why the head coach stopped to bark at the police officers outside the referees’ locker room after the last home game of the season, a 39-37 loss to Stanford – to demand they keep him away from the officials inside so he wouldn’t get into a fight.

“I don’t know that any player could match his intensity,” said Roger Steingraber, who played for Bennett at New London High School from 1969-71. “I’m guessing Tony had a little bit of a shot of matching it and some of his thoroughbreds, Terry Porter or somebody like that. But I’ve never seen a guy that was more intense on every possession.”

“I honestly do think he’s mellowed some,” said Jack Bennett, “but not to a point where he can just sit there, applaud good plays and not let it eat away at him when he sees the game played in a sloppy manner.”

As difficult as it can be to play for Bennett – Steingraber remembers the beanies and short haircuts the then 20-something coach required of his players – the honesty that accompanied Bennett’s intensity seems to have kept scores of people close to him.

Steingraber, who owns an industrial company, traveled to Los Angeles in January with three teammates from those high school teams, just to see their old coach on the sideline once more.

“I’d rather have them angry at me, but understanding what it’s going to take,” Bennett explained, “even though it’s grudging understanding, than having them think, ‘Oh, man, everything’s hunky-dory here. It’s great.’ “

In all his career stops, Bennett has never left a school with a losing record – until WSU. He has never finished with a losing season – until WSU. Were he about the records, Bennett would probably stick around for another season to reach 500 career wins. (His collegiate record stands at 490-305.)

But to assume that matters to him is to miss the point.

“The passion for games and playing well has not disappeared,” he said. “When my time comes, I’ll slide into the sunset. Some go out on a white horse. I will be chasing my golf cart.”

Just one question remain: Is that time tonight, or can the Cougars survive to give their coach one more day?