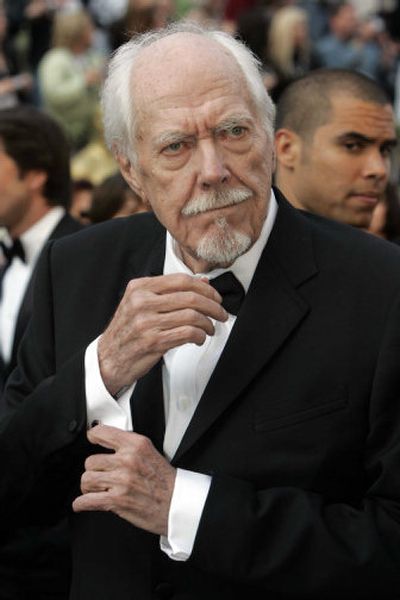

Film director Robert Altman dies at 81

LOS ANGELES – Robert Altman, the maverick director who earned a reputation as one of America’s most original filmmakers with landmark movies such as “MASH,” “Nashville” and “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” has died. He was 81.

Altman died of complications due to cancer Monday night at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.

Over the years, Altman earned five Academy Award nominations for best director – for “MASH,” “Nashville,” “The Player,” “Short Cuts” and, most recently, “Gosford Park.” His last film was this year’s “A Prairie Home Companion,” an ensemble comedy with music based on the Garrison Keillor radio show.

Elliott Gould, who made “MASH” and four other films with Altman, said in a statement Tuesday, “He was the last truly great American film director in the tradition of John Ford.”

In March, when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences honored him with an honorary Oscar, Altman revealed that he had had undergone a heart transplant 11 years earlier.

“I got the heart of, I think, a young woman who was about in her late 30s,” he told the audience. “And so, by that kind of calculation, you may be giving me this award too early – because I think I’ve got about 40 years left on it. And I intend to use it.”

A former Kansas City industrial film director who launched his Hollywood career in television in the late 1950s, Altman became a major filmmaking force in 1970 with “MASH.” A black comedy set in the Korean War, MASH memorably captured the anti-war and anti-establishment sentiments of the Vietnam War era.

New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael called “MASH,” featuring Gould and Donald Sutherland as irreverent young surgeons with a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, “the best American war comedy since sound came in.”

It was chosen as best film at the Cannes Film Festival and was named the best film of 1970 by the National Society of Film Critics.

“MASH” contained elements that became hallmarks of Altman’s filmmaking style, including a cynical, satiric tone, ensemble acting, improvisation, an elliptical, episodic narrative, a floating camera, and a layered soundtrack with overlapping dialogue.

In a flurry of filmmaking activity in the wake of his “MASH” success, Altman made seven films in the next five years that were known for their variety, creativity and vivid characters: “Brewster McCloud,” “McCabe and Mrs. Miller,” “Images,” “The Long Goodbye,” “Thieves Like Us,” “California Split” and, most notably, “Nashville.”

Many consider “Nashville,” his ambitious, song-filled 1975 drama that tells the intersecting stories of numerous principal characters, to be Altman’s masterwork.

His immediate post-“Nashville” films included box-office disappointments such as “Quintet,” “A Wedding,” and “Health.”

“No one else alive,” David Thomson wrote in “The New Biographical Dictionary of Film,” “is as capable of a dud, or a masterpiece.”

By the late 1970s, Altman had largely fallen out of critical favor and was well-known for antagonizing Hollywood unions and for badmouthing studio executives.

After his rocky relations with Paramount while making “Popeye,” the big-budget 1980 comedy musical starring Robin Williams that received mixed reviews and less-than-blockbuster box-office returns, Altman sold his Lions Gate Films and moved his family to New York City.

By 1990, Altman was described in the Washington Post as “the forgotten master,” a filmmaker who was on no one’s “A” list of bankable directors.”

Then came “The Player,” the critically acclaimed 1992 dark comedy about Hollywood greed and power starring Tim Robbins as a paranoid young movie executive. The film reinvigorated the director’s career, prompting him to joke in the press about making his “fourth comeback.”

In the wake of “The Player,” the studios began offering him scripts for high-profile, higher-budgeted projects.

Refusing to go mainstream, he used his renewed leverage to make a pet project that had previously been turned down by every major studio: “Short Cuts,” a character-laden drama based on the writings of Raymond Carver.