Shifting focus

After the Sept. 11 attacks, distraught U.S. Muslim leaders feared the next casualty would be their religion.

Islam teaches peace, they told anyone who would listen – in news conferences, at interfaith services and, most famously, standing in a mosque with President Bush.

But five years later, the target audience for their pleas has shifted. Now the faith’s American leaders are starting to warn fellow Muslims about a threat from within.

The 2005 subway attacks in London that investigators say were committed by British Muslims – and the relentless, Muslim-engineered sectarian assaults on Iraqi civilians – are among the events that have persuaded some U.S. Muslims to change focus.

“This sentiment of denial, that sort of came as a fever to the Muslim community after 9/11, is fading away,” says Muqtedar Khan, a political scientist at the University of Delaware and author of “American Muslims: Bridging Faith and Freedom” (Amana Publications, 2002).

“They realize that there are Muslims who use terrorism, and the community is beginning to stand up to this.”

Muslim leaders point to two examples of the new mind-set:

•A Canadian-born Muslim man worked with police for months investigating a group of Islamic men and youths accused in June of plotting terrorist attacks in Ontario. Mubin Shaikh said he feared any violence ultimately would hurt Islam and Canadian Muslims.

•In England, a tip from a British Muslim helped lead investigators to uncover what they said was a plan by homegrown extremists to use liquid explosives to destroy U.S.-bound planes.

Cooperation isn’t emotionally easy, as Western governments enact security policies that critics say have criminalized Islam itself.

Safiyyah Ally, a graduate student in political science at the University of Toronto, wrote recently on altmuslim.com that Shaikh, the Canadian informer, went too far.

She said the North American Muslim community “is fragile enough as is” without members “spying” on each other. Leaders should counsel Muslims against violence and report suspicious activity to police, but nothing more, she argued.

“We cannot have communities wherein individuals are paranoid of each other and turned against one another,” Ally wrote.

Yet some leaders say keeping watch for extremists protects all Muslims and their civil rights.

Salam al-Marayati, executive director of the Muslim Public Affairs Council, says working closely with authorities underscores that Muslims are not outsiders to be feared.

It also gives Muslims a way to directly air their concerns about how they’re treated by the government, he says.

“We’re not on opposite teams,” al-Marayati says. “We’re all trying to protect our country from another terrorist attack.”

In 2004, his group started the National Anti-Terrorism Campaign, urging Muslims to monitor their own communities, speak out more boldly against violence and work with law enforcement. Hundreds of U.S. mosques have signed on.

The Council on American-Islamic Relations, a civil rights group, ran a TV ad campaign and a petition-drive called “Not in the Name of Islam” that repudiates terrorism. Hundreds of thousands of people have endorsed it, according to spokesman Ibrahim Hooper.

After the London subway bombings, the Fiqh Council of North America, which advises Muslims on Islamic law, issued a fatwa – or edict – declaring that nothing in Islam justifies terrorism. The council said Muslims were obligated to help law enforcement protect civilians from attacks.

“I think everyone now agrees that silence isn’t an option,” Hooper says. “You have to speak out in defense of civil liberties, but you also have to speak out against any kind of extremism or violence that’s carried out in the name of Islam.”

But many Muslims say they’re being asked to look out for something that even the U.S. government struggles to define: What constitutes an imminent threat?

Khan says he has heard of cases in American mosques where imams have expressed extreme views in sermons, and worshippers have confronted the prayer leaders about it.

“But beyond that, what else can we do?” he says. “Do we need to hire a private detective to put on this guy?”

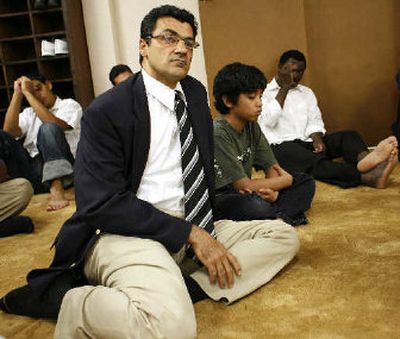

Imam Muhammad Musri, head of the Islamic Society of Central Florida, says he has tried to address this problem in the eight mosques he oversees.

He regularly invites law enforcement officials to speak with local Muslims and encourages mosque members to come to him with any suspicions, even if they overhear something said in jest.

Musri says he also speaks regularly with FBI and police to establish a relationship in case a real threat emerges.

“Here in Central Florida, talking to most people, they are literally upset by the actions of Muslims – or so-called Muslims – overseas in Europe and the Middle East, because they say, ‘We wish they would come and see how we’re doing here,’ ” Musri says.

“We know who the real enemy is – someone who might come from the outside and try to infiltrate us. Everybody is on the lookout.”