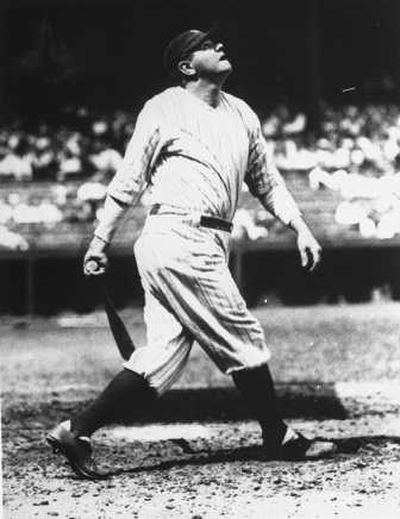

Bonds is no Babe

BALTIMORE – Being in Baltimore with the Mariners when Barry Bonds passed Hank Aaron, it seemed only fitting to go to visit The House That Built Ruth.

That would be the tiny row house at 216 Emory Street, about a Babe Ruth tape-measure shot from Camden Yards. Go upstairs, and you can see the room where The Babe was born – “the manger,” as John W. Ziemann refers to it.

Ziemann is the deputy director of the Babe Ruth Birthplace and Museum, which is housed in Ruth’s childhood home. This is where they preserve not only artifacts from his life, but the legacy and memory of the Babe, still the greatest icon that baseball – maybe sports – has ever known.

A few years ago, when Bonds was nearing Ruth’s total of 714 home runs – a number that still crackles with cultural significance, even though it has been passed twice, and probably will go down several more times in upcoming years – he fired some verbal shots at Ruth.

“As a left-handed hitter, I wiped him out,” Bonds said a day before the 2003 All-Star Game in Chicago. “In the baseball world, Babe Ruth is everything, right? I got his slugging percentage. On-base percentage. Walks. And I’ll take his home runs. That’s it. Don’t talk about him no more.”

That didn’t sit well at 216 Emory Street. Michael Gibbons, the executive director of the Babe Ruth Museum, felt obligated to respond, and he did, thusly:

“To suggest that those feats are somehow capable of ‘wiping out’ Ruth illustrates a complete disregard for the history and tradition of our national game, and its greatest player and star.

“Can Bonds ‘wipe out’ Ruth? Not today, not forever.”

Now Bonds has surpassed Aaron, too, and is at the forefront of the slugging hierarchy. In numbers, at least. Around here, they like to point out that Ruth was the first, and still the best. Certainly the most popular, as the bustling museum, with more than 30,000 visitors a year, attests.

“I don’t think you’re going to see people come through Barry Bonds’ house as much as you see people come through Babe Ruth’s house,” said Ziemann.

They don’t attempt to smooth over the rough edges of Ruth’s life at the Babe Ruth Museum. As Ziemann said, “This was a child that didn’t have his first drink until he was 5, didn’t have his first plug of tobacco until he was 6, didn’t have his first cigarette until he was 4.”

Ruth’s adulthood was a monument to wretched excess, with vices that ranged from booze to food to women. He could be tough to manage, and even teammates found him maddening on occasion.

Those faults were modulated by a far-reaching love of children that was romanticized to absurd promotions in movies like “The Babe Ruth Story” but which historians say was genuine.

Considering his appetites, one has to wonder how Ruth would have reacted to the temptations of steroids had he played in the modern era. Historian Bill Jenkinson, who wrote the excellent recent book “The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs,” says it’s a legitimate question.

And he believes the answer is no, and uses an anecdote in making his case. After the 1922 season, a year in which Ruth’s off-field behavior had been particularly wild, he was berated at an Elks Dinner by assemblyman Jimmy Walker, a future mayor of New York.

“Ruth openly wept,” Jenkinson said. “He vowed to lead a clean life and come back the next year with his best season. He was emotionally stricken by the charge. He did what he said. He reported to camp in 1923 at 201 pounds, and had his best season.

“He was pretty rough coming out of St. Mary’s (the Baltimore reformatory and orphanage for boys to which his parents sent him) in 1914. If given a choice then, I couldn’t answer that question. But within a few years, he supplanted Ty Cobb as the game’s pre-eminent player, and he took that role extremely seriously.

“I can guarantee nothing, but I doubt very much he would have done anything to risk that status.”

Jenkinson, who meticulously researched Ruth’s career, virtually homer by homer, posits in his book that Ruth would have hit 104 home runs in 1921 under modern rules and conditions, and more than 1,000 in his career. And Jenkinson’s studies have convinced him Ruth consistently hit them farther than anyone.

“If there is going to be another Babe Ruth, we haven’t seen him yet,” Jenkinson said. “Bonds after 1999 has been great. He’s still not Ruthian. (Albert) Pujols, (Alex) Rodriguez, (Ken) Griffey Jr. – these guys are amongst the best ever. They’re not Ruthian.”

All have their place in baseball lore, but there’s still only one Babe. Jenkinson has called him a “biological aberration,” and believes he was a prodigy the ilk of Mozart or Einstein.

“This guy is transcendent,” he said. “Our species produces an anomaly like that on occasion. In baseball, he’s it.”