Elvis sightings

In the summer of 1957, girls across America – even sleepy Spokane – loved Elvis.

So many kids and teens turned out on July 31 to see the opening of Elvis Presley’s second film, “Loving You,” that the line at the Fox Theater extended three downtown blocks.

“At showtime there were no injuries, but pressure of the crowd of young people near the Fox entrance broke out a display window of the Wurlitzer Organ company,” the Spokane Daily Chronicle reported.

But that sold-out movie showing was nothing compared to what was coming.

Ten days after the crowd broke the window, newspapers announced that Elvis himself was coming to Spokane for a Friday-night performance on Aug. 30.

Almost 50 years ago, Elvis’ concert at Memorial Stadium, now called Joe Albi, was unlike anything Spokane had seen before: screaming pubescent girls, a man in a gold-sequined jacket … and those hips.

Hips that moved … in those ways.

Who could blame those girls?

Elvis was, in the words of a Spokesman-Review reporter who attended the concert, “a young man who embodies more sheer animal magnetism than many of the ‘captive audience’ – police, reporters, photographers, ushers, first-aid men – were able to believe had existed.”

Other big-name artists who sang in Spokane – like homegrown Bing Crosby – entertained in smaller venues, like theaters, said Alan Hanson, author of the new book “Elvis ‘57,” about Presley’s concerts that year.

Elvis was the first to hold a concert in Spokane at a pack-‘em-in venue like Memorial Stadium.

“In my mind, that’s the biggest musical event that’s ever been in this town,” said Hanson, a retired North Central High School teacher.

But if the show was big by Spokane standards, by Elvis standards it was much more modest.

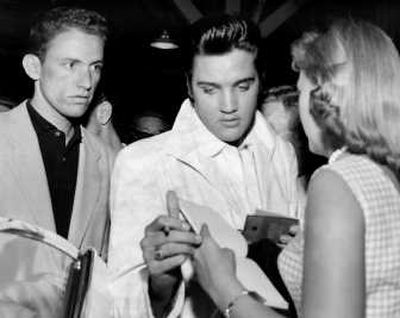

When Elvis, who was afraid to fly, arrived in Spokane by train on the Thursday before the show, he was greeted on the platform by only a dozen or so fans, a much lower turnout than in other cities.

This might have reflected the city’s conservatism, Hanson said. Spokane parents in 1957 may have allowed their daughters to see a concert, but they sure as heck weren’t going to let them greet Elvis Presley on a train platform at 11:20 p.m.

And while press reports at the time said more than 12,000 attended the concert, city finance records showed only 8,341 people paid to get in (with gross receipts of $21,708).

The difference isn’t surprising, according to Hanson: Elvis’ manager, Col. Tom Parker, often embellished concert attendance.

Organizers had planned to fill the stadium and place the stage at an end zone, but when tickets didn’t sell as briskly as hoped, the layout was changed to seat only the west stands and Elvis was placed at midfield, Hanson said. People who bought $3.50 tickets found they had to sit in $2.50 or $1.50 seats.

George Klein, an Elvis friend who was at the Spokane concert, remembered that Presley was concerned about the Northwest tour, his last one before entering the Army, because he would be using outdoor stadiums where he couldn’t get close to fans.

He also was worried about the weather, Klein said last week from Memphis, where he was attending events commemorating the 30th anniversary of Elvis’ death.

“Don’t worry,” Klein remembered Parker telling Elvis and others on the tour. “We have the only license to sell raincoats.”

As it turned out, they weren’t needed anyway.

Like most of his 1957 shows, Elvis started the show with “Heartbreak Hotel,” Hanson said.

“His long hair flopping and his sequined gold jacket glittering in the pink footlights,” he sang 18 songs “in the midst of a huge, solid bubble of sound,” The Spokesman-Review reported.

“Those who went out to hear the popular rock ‘n’ roller didn’t stand a chance; you simply couldn’t hear, the screaming was so loud,” wrote Chronicle reporter Jim Spoerhase.

Jack Latta, a Spokane police officer who served as part of Presley’s security for the event, remembers being able to hear Elvis fine. But then again, he wasn’t listening that hard.

“I hoped it would get over with so I could go home,” he said last week.

The girls in the crowd, while loud, were well-behaved, he added.

Mostly, “they were screaming a lot,” said Latta, who escorted Elvis back to the Ridpath Hotel after the show. “He did a lot of gyrations.”

Still, the concert was not without incident.

“To say the teenagers loved Presley would be putting it far too mildly,” Spoerhase wrote. “They even loved the dirt he kneeled on – evidenced by the fact about 50 young girls swarmed onto the dirt track of the stadium to scratch up handfuls of dirt where Elvis had kneeled during his final number.”

By all accounts, girls, most of them 14 and younger, filled the crowd.

“The fathers were always against Elvis,” Hanson said. “But the mothers would often side with the girl and she would be allowed to go.”

After his Spokane performance, Elvis moved on to Vancouver, B.C., Seattle, Tacoma and Portland.

Spokane was left to ponder what had come over its daughters.

The Spokesman-Review’s editorial page sought to reassure parents that that the wiggly hips their children saw at Memorial Stadium were not a sign of societal decay:

“Of course, his popularity won’t last, but he has given the youngsters an occasion for a release from conformity.”

The Chronicle saw it differently.

Just below an editorial that praised baseball pitcher Bob Feller, who was visiting Spokane, as “a happy and famous man with the unmistakable stamp of class,” the Chronicle questioned Elvis’ treatment of the city.

“Even the kindliest of mature critics at Spokane Memorial stadium agreed that Presley’s physical exercises were of a fundamentally base nature,” the editorial said.

Elvis would not return to Spokane to perform until 1973. He came a last time in 1976 at the Spokane Coliseum. Reviews for those shows in both the city’s newspapers lavished praise on the concerts. No one wrote of pending doom based on Elvis’ behavior.

Latta, the police officer, also worked Elvis security in 1976. He remembered that the crowd was different – rowdier than the one that came in ‘57.

Presley “put on quite a show,” he said, but The King, too, had changed. He was out of shape and sweated profusely.

“He was on his way up the first time,” Latta said. “He was on his way down the last time.”