SKY’S NO LIMIT

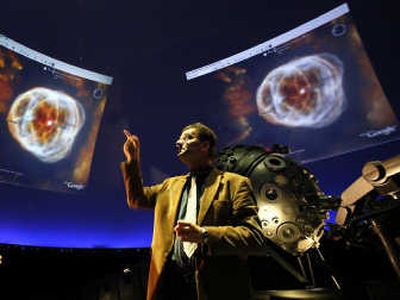

The same people who enabled your computer to zoom over your neighborhood or look anywhere on Earth have done the same for the heavens. With a mouse click using Google Sky, people can now search the universe from their desktop.

Launched last month, the free Google Sky application – a part of Google Earth – allows anyone to look up and “see” the sky from any point on Earth. The same way Google Earth uses satellite images of the planet, the company’s Sky product gives viewers zoomable images of the heavens.

Google Sky displays thousands of images taken by earth and satellite telescopes, along with a wonderful feature that lets you zoom in or out and examine objects in detail. Many of the sky images are from the Hubble Space Telescope, while others come from astronomy teams from around the world.

“By working with some of the industry’s leading experts, we’ve been able to transform Google Earth into a virtual telescope,” Lior Ron, a Google product manager, said in an interview from his office in Tel Aviv.

Scientists have been collecting space images for dozens of years. Google Sky has taken all those images and gone the next step. It stitches together the sky map with thousands of those images, along with popup tools that explain how stars are formed, what happens when galaxies collide or how planetary nebulae differ from other celestial objects.

What this offers, said Andrew Connolly, a University of Washington associate professor of astronomy, is the chance to see things no one else has seen. Because of the Google zoom option, the viewer can zoom into a deep space image and eventually focus on a part of the sky captured by a telescope.

Said Connolly, one of several astronomers who worked with Google on the project last year, “This gives you the chance of being the first pair of eyes to look at that part of the night sky at that depth.”

The huge fan base of Google Earth has resulted in thousands of user-created “layers” that can be added to the Google Earth program, showing additional levels of information. The same richness and diversity is occurring with Google Sky, said Ron and Connolly.

Google has a sky gallery that helps people find and learn how to use those add-ons and extra features, at http://earth.google.com/ gallery/.

The result, said Connolly, is to make Google Sky an interactive resource where people can share discoveries and help professional astronomers do their job better.

Amateur astronomers might point a good telescope at the sky one night south of Spokane and capture images of an unusual event, perhaps a new comet. Using the option of adding new information to Google Sky, they could upload those images. Users on the other side of the planet could view those images in Google Sky, said Connolly.

Ron said Google Sky was a “20 percent” project. All engineers at Google can spend one-fifth of their work time on any test research project they care to explore. A large number of engineers chose to develop Google Sky and the result was a product the scientific community is embracing enthusiastically, said Ron.

He said the final intent is creating a tool that reveals the vastness of the universe.

“With Google Earth, everyone starts by looking at their own house. That’s fine. But with the sky, there’s no home to start from. The fun stuff comes from exploration. You just browse and see fantastic examples of what’s out there. And there is a lot out there,” said Ron.