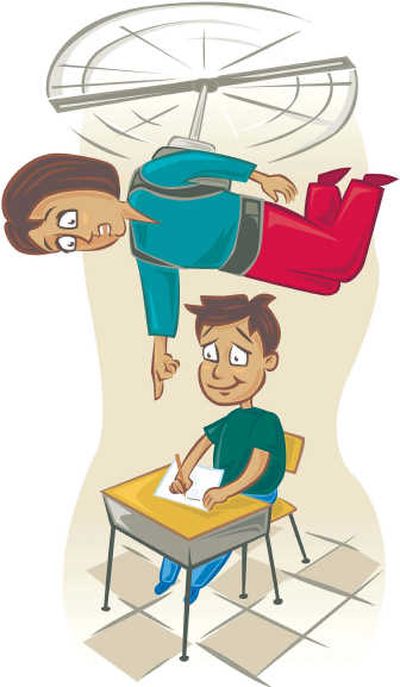

Hurtful hovering

As a consultant to several universities, Helen E. Johnson has noticed a huge increase during the past decade in bright students who lacked the maturity to handle college on their own.

“They need constant reinforcement and support,” said Johnson, co-author of the parent guide “Don’t Tell Me What to Do, Just Send Money.” “They never really forge intimate relationships with their peers. … They don’t have judgment. They can’t take criticism.”

What do many of these students have in common? Their parents were over-involved in their children’s classrooms, usually from an early age.

Typically, it started in elementary school, where their well-meaning “helicopter parents” (so named because of their habit of hovering over their kids) spent hours volunteering in their classrooms, editing or rewriting assignments and trying to make sure nothing ever went wrong.

But it’s a tricky, touchy subject. Parents, after all, only want the best for their kids. Who can blame them? In most instances, teachers embrace the help parents provide. They don’t want to anger or discourage them.

So with autumn in the air and the school year in full swing, many parents may wonder: How much help is too much? Finding the right balance regarding their children’s education might be one of the biggest challenges they face in the 21st century.

Students who get too much help growing up often don’t last long at college. Johnson, who spent several years working at Cornell University in New York and now lives in North Carolina, said the stress of dealing with the real world can lead to self-destructive behaviors, such as eating disorders or cutting themselves. They may turn to antidepressants.

“This is a really unattractive outcome of hyperparenting,” she said.

Novelist Jane Porter, who grew up in Visalia, Calif., explores this modern parental dilemma in her new book, “Odd Mom Out.” A former teacher and mother of two boys, ages 9 and 12, Porter sometimes struggles with how much to get involved.

Watching other women near her home in Bellevue, Wash., invest so much time and energy in their kids’ classrooms led to the “Odd Mom Out” plot about a working mom who feels compelled to compete with other moms when she’d really rather not.

“A lot of moms are very afraid if they don’t do this that their child will miss out on opportunities in life,” said Porter, a former teacher. “They’re not doing it because they’re malicious. But there’s this feeling that ‘Unless I take every extra parenting class out there, unless I take all these courses, unless my child attends this very private school, my child is going to miss out on something very significant.’ “

Susan Macy, an instructor at Fresno State’s Kremen School of Education, said efforts to get ahead always have relied on education. But expectations have been raised, and it’s one area in which parents feel they can exert control.

It can become a vicious cycle that starts when kids are young.

Macy said parents believe “My child needs to have an excellent first-grade education so they can meet standards in sixth grade, so they can do that in eighth grade, and in high school, so that they’ll go to a fabulous college, so they can get the job of their dreams, so they can get lots of money, so they can have influence in the world and make the world a better place.”

It’s a lot to put on a 6-year-old’s shoulders.

How did we arrive here? Johnson said it required a “perfect storm” of social and scientific developments during the 1980s.

Americans began waiting until they were a little older to start having children, and they had smaller families. Johnson said the second wave of feminism contained many highly educated women who decided working wasn’t all that great. If anything, feminism was about choice.

“The affluent ones decided to stay home and make parenting the most vital enterprise of their lives,” she said.

Porter has seen moms take the energy they once devoted to careers and pour it into their kids’ schools. The results aren’t always pretty.

“There’s a point where a parent owns the child’s work or owns the outcome more than a child does,” she said. “Each of us has been through school. Did those grades belong to our parents or ourselves?”

But perhaps the biggest factor that created this situation, Johnson said, was scientific research 25 years ago that suggested brain development starts earlier than anyone had previously realized, even in utero.

In theory, that meant we had more time to teach children. People instead often became anxious that they were wasting an opportunity to get started.

Globalization plays a role as well. Efforts to raise test scores were designed in part to help U.S. students compete with bright foreign students. But, in many cases, they’ve frustrated educators and increased anxiety among parents.

“We’re so afraid we’re not keeping up with other countries,” Porter said. “It’s all trickled down. We feel squeezed in the work world, in the business world of corporate America, so we squeeze at home, and we squeeze the kids.”

Parents investing too much time and energy in their children’s lessons can have unintended consequences. Their mere presence changes the classroom dynamic.

“Kids act differently when parents are there,” Porter said. “They’ll either try to show off more, to be funny, or they’ll want to think they can break class rules because, hey, that’s somebody’s mom or their mom.”

Macy said some children are afraid to look bad with mom or dad watching.

“They won’t take risks,” she said. “Good teachers have established this risk-free environment where you take a chance and answer the question, even if it’s wrong. Then the teacher knows where you are and can go back and teach you.”

Some kids figure their parents will keep track of assignments, essentially becoming their secretary.

“We don’t want children to become reliant on their parent in the classroom,” said Macy. “One of the things they’re learning is to become independent.”

Sometimes it’s hard for parents to understand that they shouldn’t act as classroom advocates for their kids. It puts a teacher in a tough position when choosing students for special assignments – and one of the kid’s parents sits there, waiting expectantly.

Johnson warns parents that they’re handicapping their kids “by creating false opportunities for them.” It also can be painful to watch your child make a mistake. But there are worse things.

“Intervening before a child has the opportunity to look at what they did, think about what they did and try to figure it out for themselves is robbing that child of critical developmental stages that are necessary,” she said. “It’s not easy for a parent to watch it, I agree with that. But it’s absolutely essential.”

Marcia Kaser of Fresno, Calif., who taught for more than 30 years before retiring five years ago, said solving problems builds confidence.

“There’s a sense of confidence that a kid gets when he sees that he handled a situation OK,” she said. “It’s kind of fun. It earns respect from other people. He learns to trust himself.”

One of the problems with some helicopter parents is that they believe they can do a better job than the teachers they’re helping.

Porter had a mom come into her classroom and say, “I don’t know what the big deal is. I was an English major. I could teach English.”

She bit her lip and said nothing but thought to herself, “go ahead, teach it to 35 12-year-olds, 11-year-olds, all at the same time.”

Macy said it’s harder than it looks.

“Everybody feels like they’re an expert in teaching because everybody’s gone to school,” she said. “Everybody’s taken care of 20 kids at a birthday party, so they think they know how to control 20 kids and keep them interested and involved. But it’s very different than that.

“It’s not easy to describe how the seasons happen to a 5-year-old. It’s not easy to describe the metamorphosis of a butterfly to a second-grader.”

So what should a well-meaning parent do? Pay attention. Reflect on your motives. Johnson said there are signs you’ve crossed the line.

“Trying to tell the teacher what to do,” she said. “Trying in subtle ways to arrange the experience so that it benefits your child. … Or pointing out to the teacher the obvious brilliance of your child.”

She said no parent should be in the classroom more than once a week.

“If you’re in the classroom every day, look in the mirror and remind yourself that you need a life,” Johnson said.