Living in ‘LIMBUS’

Harriet Sanderson sees art in infirmity.

The Seattle artist’s show, “Limbus,” which comes to Spokane this week, features canes, beds and chairs, among other mixed-media installations.

It’s a world Sanderson, 60, knows well.

She contracted polio when she was three years old. About 35 years later, she developed post-polio syndrome, which causes progressive muscle weakness and atrophy.

“I don’t represent in fact what my body is or what my disability is, or anyone else’s, for that matter,” Sanderson says. “Rather, I rely on my day-to-day experience to sift through my consciousness and, in that process, how I’m feeling physically and psychologically is translated into symbolic materials.”

Polio affected most severely the upper right portion of her body, and she has little use of her right arm. The effects of post-polio syndrome have been more widespread, and Sanderson says this exhibit at the Jundt Gallery at Gonzaga University will likely be her last one of this magnitude. (See page D13 for details)

“The whole right side of my body is weaker,” she says. “My legs are both weakening. All the muscle structure is weakening.”

Post-polio syndrome affects one-third to one-half of all polio sufferers.

“It’s a progressive wearing out of the nerve endings to the muscles that had previously been paralyzed by polio,” says Dr. Vivian Moise of Rehabilitation Medicine in Spokane, who sees a large number of post-polio patients. “It’s not a return of the virus or an infection or something like that.”

The initial polio infection kills off some of the nerves in the spinal cord that control muscle. Surviving nerves nearby create “sprouts” to “adopt the orphaned muscle,” Moise says.

“Sprouts aren’t as thick and hardy as the original nerves and they don’t last,” she says.

People who were 10 years old or older when they got polio, those who had paralysis in all limbs and those who needed an iron lung are most likely to contract the syndrome 30 to 50 years after the original diagnosis, Moise says.

Treatment is centered on moderating physical activity, breaking up exercise with rest periods, she says.

“Overtiring speeds up deteriorating,” she says.

So, she might encourage someone to ride an exercise bike but to take a one minute break for every three-to-five minutes of exertion.

“Doing no exercise at all will also make you weaker,” she says. “There’s this very fine line between not enough exercise and too much exercise.”

But Moise, who sees a couple dozen patients with post-polio syndrome, says getting her patients to take it easy is the biggest problem.

“Polio survivors are traditionally over-doers,” she says. “They’re overachievers. That’s how they learned as kids to surpass their paralysis.”

A look at Sanderson’s resume bears that out. She has worked as a scientific illustrator and freelance designer, received a master’s degree from the University of Washington and has received numerous awards for her work.

Her artwork has been shown around the world.

Says the Seattle writer and critic Robert Mittenthal:

“Harriet Sanderson is an artist enabled by an acute awareness of her own physical limits. She has spent a lifetime struggling with constraints, having virtually no use of her right arm since she contacted polio at a young age. Arranging and rearranging furniture in a sort of Zen-like rock balancing exercise, Sanderson works like Sisyphus: rolling a rock uphill, turning it carefully upward in anticipation of the inevitable moment when balance is lost, when the rock tumbles back down to the foot of the hill.”

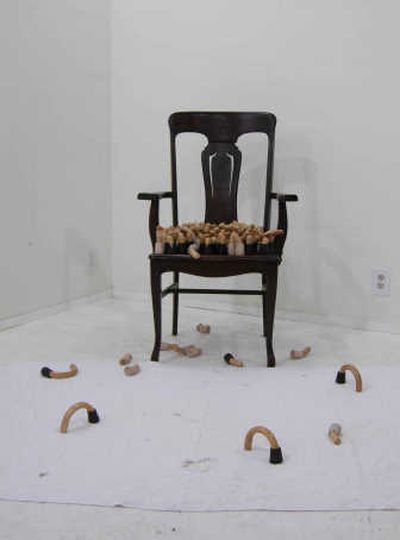

One of her installations shows a bare chair, woven through with a serpentine configuration of walking stick segments.

“They curve and undulate and go straight,” she says. “It’s real knobby and arthritic-looking.”

The piece was inspired by visiting her mother in nursing homes over a period of five years. There were always a couple of residents sitting near the front desk, some of whom did not seem very welcoming.

“It’s very intimidating for a first-time visitor,” she says.

Sanderson says she used to bristle at being considered a “disability artist.” But that stance has changed over time, she says.

“I would prefer to be considered an artist, first and foremost,” she says. “As time has come by and I’ve become less and less able to do my chosen kind of work, I’ve been investigating what disability really means.”