Clarke’s ‘Last’

‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ author’s final book due Tuesday

Arthur C. Clarke’s health was failing fast, but he still had a story to tell. So he turned to fellow science fiction writer Frederik Pohl, and together the longtime friends wrote what turned out to be Clarke’s last novel.

“The Last Theorem,” which grew from 100 pages of notes scribbled by Clarke, is more than a futuristic tale about a mathematician who discovers a proof to a centuries-old mathematical puzzle.

The novel, due in bookstores Tuesday, represents a historic collaboration between two of the genre’s most influential writers in the twilight of their careers.

Clarke, best known for his 1968 work, “2001: A Space Odyssey,” died in March at age 90; Pohl is 89.

“As much as anything, it’ll be a historic artifact,” says Robin Wayne Bailey, a former president of Science Fiction Writers of America and a writer. “This is a book between two of the last remaining giants in the field.”

Clarke originally intended “The Last Theorem” to be his final solo project, and he began writing it in 2002.

But progress was slow because of his poor health, and he missed the book’s original 2005 publication deadline. Worried the book wouldn’t be published at all, he began to search for a co-author.

While the search was under way, Clarke would often tell his assistants, “I hope ‘The Last Theorem’ won’t become the lost theorem!” according to Nalaka Gunawardene, one of his aides in Sri Lanka.

Pohl said he volunteered for the job and set about making sense of 100 pages of notes Clarke left him. About 40 or 50 pages of scenes were fully written, but the rest contained only undeveloped ideas. On some pages, there were only one or two lines of text, Pohl said.

Clarke, who lived in Sri Lanka until his death and had battled post-polio syndrome for decades, became bedridden after breaking bones in his lower back. Difficulties with memory meant he couldn’t recall enough about what he’d written in his notes to help Pohl decipher them.

“I started out by asking him for information on things in the book,” Pohl said during an interview at his home in Palatine, Ill. “And he e-mailed me back and said, ‘I don’t know. I have no idea what I was thinking of when I wrote that.’ It had just gone right out of his head.”

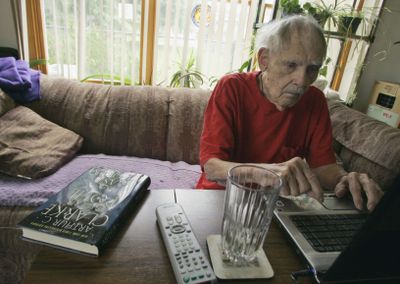

Pohl has his own troubles. He suffers from poor muscle response in his hands and feet. He wrote much of the novel on pen and pad, his wife, Betty, transcribing the scribbles onto a computer; but his handwriting is now illegible.

Typing, too, is difficult because his right hand remains bent and does not unfold in the proper way.

But together, the two longtime friends worked through the novel.

Chris Schluep, senior editor at Random House who worked with Clarke on the book’s concept from the beginning, said the final manuscript maintained a “golden thread” of Clarke throughout but was a clear collaboration between both authors.

“It’s sort of a worthy exclamation point on two pretty incredible careers,” Schluep says.

Clarke is known for forecasting scientific inventions in his novels: In 1945, he predicted the development of communications satellites, 12 years before the launch of the first artificial satellites. As a result, geosynchronous orbits, which keep satellites in a fixed position relative to the ground, are nicknamed “Clarke orbits.”

“The Last Theorem” includes a weapon called Silent Thunder that neutralizes all electronic activity in a given area to harmlessly disarm entire nations.

Then there’s the space elevator, a cord suspended from an orbiting object in space that can pull objects from Earth, rather than rely on rocket power to launch them.

Pohl says his research and conversations with friends who are scientists convince him both will one day exist.

“If we can somehow figure out what possible futures there might be,” he says, “you can try to encourage the ones you like and avoid the ones you don’t.”

Pohl says the type of work he and Clarke did was different from much of what is written today. Rather than delving into difficult subjects like astronomy, math and physics, he says, young writers sometimes turn to an easier route by writing fantasy.

“Science fiction is sometimes a little hard,” Pohl says. “Fantasy is like eating an ice cream cone. You don’t have to think a bit.”

By now, Pohl has outlived the other titans of his genre. All the men he has collaborated with over the decades – including Jack Williamson, Isaac Asimov and now Clarke – are dead.

Pohl and Clarke met in the 1950s in New York, where Pohl was a literary agent during the “Golden Age” of science fiction.

Clarke, visiting the United States for the first time, sought out a group of science fiction writers called the Hydra Club, of which Pohl was a part. The men corresponded over the years and traveled together to Japan and Brazil.

At the beginning of their collaboration, in 2006, Clarke made edits and suggestions on Pohl’s writing. Although they never saw each other face to face during that time, the two would exchange e-mails and speculate about different scenarios.

“And then he began getting sicker,” Pohl says. “When he was in the hospital he wasn’t allowed to read, and when he was out of the hospital sometimes he physically couldn’t read.”

On Clarke’s 90th birthday in December 2007, Pohl sent him a letter reminiscing about a time they were young and spry, jousting on bicycles in Georgia.

But Clarke didn’t respond, Pohl says. His health was getting worse.

Still, Clarke e-mailed Pohl in March to say he was pleased with the final manuscript.

“He was also enormously relieved that the novel could be completed,” says Gunawardene, his aide.

The next day, Clarke was rushed to the hospital with difficulty breathing and placed in intensive care. He died three days later, on March 19.

Bailey, the former Science Fiction Writers of America president, said Clarke’s and Pohl’s books were some of the first science fiction books he and other authors of his generation read – which lends even more significance to “The Last Theorem.”

“They had an impact on almost everybody who’s writing science fiction today, in one way or another,” Bailey says. “We may not see another Pohl book, either.

“We just don’t have these kind of writers in the genre anymore. They were at the beginning, pretty much, of the genre, and have remained presences throughout.”