Foes once joined forces

Merged ‘Car-Pitts’ got walked all over during 1944 season

TAMPA, Fla. – They wore hand-me-down jerseys, the little rips and tears widening with every loss. The holes at quarterback and kicker were more obvious.

The brief World War II merger of the Steelers and Cardinals may have helped the NFL. It sure didn’t benefit anyone who spent that season shuttling to home games in Pittsburgh and Chicago.

“We were terrible,” 91-year-old former lineman Chet Bulger said. “You’d get beat so bad, you’d cry.”

Long, long before the franchises reached this year’s Super Bowl, they teamed together in 1944 to create a much different legacy.

At 0-10, the ragtag outfit got outscored by an average of three touchdowns per game, threw a record 41 interceptions and set a league mark that still stands for the worst punting.

Their nickname seemed inevitable: the Car-Pitts. As in, every team walked right over them.

“That was true,” recalled Vince Banonis, who played two games while on weekend furlough as a Navy lieutenant. “We got massacred every week.”

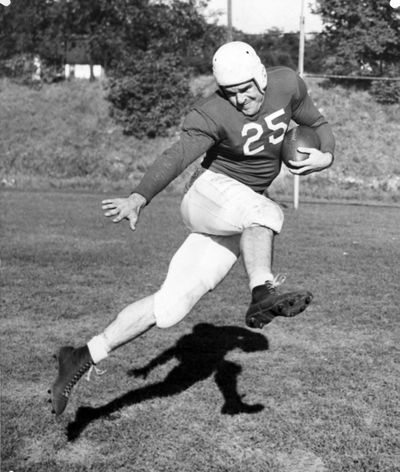

Beset by fights, fines and suspensions in a rough-and-tumble era, there was hardly a Ben Roethlisberger or Larry Fitzgerald among them. Their lone ace, Johnny Grigas, threw away his leather helmet and skipped town before it was over.

About an hour before the wrap-up, a 49-7 rout by the Bears at Forbes Field, the Car-Pitts discovered Grigas already was on a train.

The former Holy Cross star left a note for his hotel roommate. “This is the end,” Grigas wrote, saying he didn’t care to finish up on a frozen field.

“I thought he’d gone to become a priest,” Bulger said. “He’d had enough.”

So had many of the guys. Most of them came from the Chicago Cardinals – they were in the midst of a 29-game losing streak, and only the merger kept them out of the record book for consecutive defeats by a single franchise.

A few guys straggled over from the Steelers. They’d joined Philadelphia in 1943 as the “Steagles” after military service left both teams short-handed, but the sides broke apart when the season ended.

“They were at each other’s throats, the way I heard it,” Banonis said.

In April 1944, the NFL suddenly found itself with 11 teams when the Cleveland Rams rejoined the league and the Boston Yanks entered. That caused scheduling problems, so commissioner Elmer Layden, one of the original “Four Horsemen of Notre Dame,” asked Steelers owner Art Rooney and Cardinals boss Charles Bidwill if they’d be interested in a merger.

The patriarchs of the families that still own the franchises agreed. A few months later, the combined club went off to training camp in Waukesha, Wis.

“We were all sitting there on the porch the first day,” Bulger said. “We’re all just looking at each other. These were guys you’d tried to beat up before. Finally, one of the co-owners, Bert Bell, says, ‘You’re going to have to get together.’ ”

Finding a nickname for the team was a little more challenging. At the outset, there were several: the Chi-Pitts, the Card-Pitts and Cardinals-Pitt, among them.

A 3-0 loss to Sammy Baugh and the Washington Redskins in an exhibition game gave them hope. They lost the opener to the Rams 30-28 on a late TD, then actually won a week later – too bad for them, the 17-16 victory over the New York Giants came in an exhibition game, a frequent occurrence during the war.

From there, it got real bad in a hurry.

Team management fined three players for “indifferent play” after a 34-7 loss to the defending champion Bears.

None of their quarterbacks could run the popular T-formation, and the famed “Notre Dame box” didn’t work, either. Military commitments caused chaos with the roster, and replacements signed off the sandlots showed up in Pittsburgh for practice.

“It was an odd year,” Bulger said. “We got all mixed up.”

Especially when it came to kicking. They averaged only 32.7 yards per boot.

“Everybody tried to punt. We all tried in practice,” Bulger said. “We couldn’t find anyone.”

Co-coaches Phil Handler of the Cardinals and Walt Kiesling of the Steelers were at a loss. Kiesling had been a Hall of Fame lineman, but wasn’t nearly so successful as a coach. Many years later in Steelers camp, he cut a young quarterback named Johnny Unitas.

Art Rooney also thought Kiesling spent too much time around the horse tracks in Chicago. “He studies the Racing Form more than he does the playbook,” Rooney once said.

The next week, after the Giants whacked them 23-0, it was clear this merged team was brutal.

“The Card-Pitts played the role of a red plush rug this afternoon as the undefeated Giants paraded over and past them,” the Chicago Tribune reported.

Then came a wild brawl with the Redskins, with Gil “Cactus Face” Duggan among the players ejected once police restored order. There were two losses at their other home field, Comiskey Park in Chicago, and that final rout by the Bears.

Overall, they were outscored 328-108.

For Bulger and Banonis, the good times came later. The rugged two-way linemen played together in 1947 on the last Cardinals team to win the NFL championship, and Banonis won a pair of titles with Detroit in the early 1950s. Bell also made out well, later becoming commissioner.

Banonis, now 87 and in a wheelchair, will be rooting for the Cardinals in the Super Bowl. During a telephone interview from his home in Southfield, Mich., he began singing the team fight song from long ago.

“Hail Chicago Cardinals, crimson and white,” he belted.

Told of Banonis’ performance, Bulger laughed.

“He was always singing these Lithuanian songs,” Bulger said. “Oh, what a football player he was.”

After nine years in the NFL, Bulger coached and taught for 30-plus years at De La Salle Institute in Chicago. The school named its main athletic field for him, and he continues to help with its fundraising efforts.

And he keeps rooting for his old team.

“I’m still a Cardinal, always a Cardinal,” he said. “I can’t see too well anymore, but I’m going to get up real close to the TV to watch that game. Maybe we’ll win that Super Bowl. Wouldn’t that be something?”