Hanford evictees visit ranch

Family returns 66 years later

KENNEWICK – Ludwig Bruggemann was about 5 years old on the late winter day in 1943 when two jeeps drove up the road to his family’s ranch on the banks of the Columbia River.

Army officers with papers stepped out to say the words that would change his family’s life: “You have two weeks to leave.” Their 400-acre ranch had been condemned as part of the effort to win World War II. About 1,500 people, many of them members of farm families, would be displaced from the 586 square miles that now are part of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation.

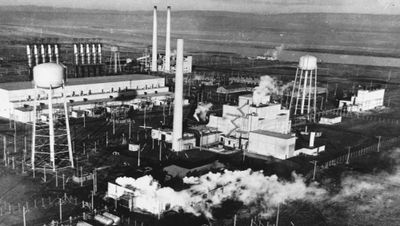

Not until after the war ended did they know that the U.S. government had picked the area because of its remote location and abundant water and power to produce plutonium for the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, helping end WWII.

Bruggemann and his little sister, Paula, would listen to their father talk about the ranch until he died.

“He never got over it,” said Debbie Holm, daughter of Paula Bruggemann Holm. “It was a really, really sad thing for him.”

For decades Bruggemann would occasionally drive his parents, Paul and Mary Bruggemann, to the Vernita bridge area to peer down the Columbia River to try to get a glimpse of the ranch. They thought they could make out the stone house that had kept them cool on blistering Mid-Columbia summer days.

But none of the family set foot on the ranch again until this spring.

Then the Department of Energy and the Tri-City Development Council arranged to take the Bruggemann siblings back for their first visit to their early childhood home since their parents hastily packed up their possessions 66 years ago.

Ludwig was visiting from Germany, where he now lives, and Paula brought along her husband, Bing Holm, and daughter Debbie, all of whom live in Yakima.

They didn’t know what to expect. Most of the pre-World War II buildings at Hanford were demolished by the government, other than the tiny White Bluffs bank and the Hanford high school.

But they believed one of the ranch’s buildings remained standing.

The Bruggemann descendants returned to the ranch equipped with family photo albums, the original plot of the ranch and a diagram drawn by Paul Bruggemann.

The 400 acres were neatly divided into sections with spaces saved for thousands of apricot, cherry and other fruit trees. Large sections were reserved for vineyards. The ranch had sheep, and space was allocated for clover, alfalfa and rye grass pastures.

By 1943 the ranch, which Paul and Mary Bruggemann had purchased as the Von Herberg Ranch, had 100 acres under plow. Although the family doesn’t remember exactly when the ranch was purchased, the family owned it at least as early as when Mary was pregnant with Ludwig.

They were set to bring in their first major crop of cherries, peaches, pears, apricots and grapes in 1943, Ludwig Bruggemann said. In addition to sheep, pictures show turkeys at the ranch, and Bruggemann remembers goats because “one knocked me down when I was 5.”

On a recent day, a minibus carried the family down the paved road that has been little used since the Bruggemanns used to drive to the nearest community, the former town of White Bluffs.

Sure enough, one of the ranch’s several buildings remained standing – a long, cobblestone building with decorative touches like the arched windows underlined with rows of smaller stones. It took some comparisons with family photo albums to conclude it was the warehouse.

The family couldn’t get too close. Sometime in the decades since World War II, the government surrounded the warehouse with a tall chain-link fence topped with barbed wire.

A sidewalk still crosses the lane from the warehouse to the foundation of what the family concluded was once a large barn nearby. But the cobblestone home was gone.

From where the wide steps once descended from the house in graceful half circles, the family could see four plutonium-production reactors lining the Columbia River, starting with B Reactor, the world’s first full-scale reactor.

Two things plagued his father at the ranch, Bruggemann remembered: the many stones that kept pushing up in his fields and the pump house that irrigated his land.

At the river, only pieces of the pump house remained – foundation made of concrete and more river rock, piping in concrete squares and some boards that may have once been part of its sides.

Paul Bruggemann, like so many of the farmers and business people who were evicted, believed the government paid too little for his ranch. But a German citizen at the time, he was cautious.

He would become an American citizen a few years later and did eventually ask for more compensation in court. But a judge asked him to show his profits from the ranch.

“He was right in front of the profits,” with his orchards and vineyards just set to produce their first major harvest in 1943, Bruggemann said. The family also needed more than two weeks to sell their farm equipment and animals, he said.

The family eventually settled on 12 acres on what’s now Englewood Avenue in Yakima and develop an orchard.

When the subject of the former ranch would come up, Mary Bruggemann would say “Let’s talk about something else,” Debbie Holm said.

But her grandfather did not tire of the subject. He never had the fondness for the Yakima orchard that he had for his sweeping spread stretching under the desert sky down to the Columbia River.